Come Rain Come Shine: The Weather in Japan

Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s northern island Hokkaidō was hit by a heat wave on June 3 that sent temperatures soaring to over 37°C in some areas. Usually seen as a haven from summer humidity for Tokyoites and others living further south, the island experienced record-breaking highs, prompting the Japan Meteorological Agency to issue warnings against heatstroke.

Japan contends regularly with the forces of nature, including earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, as well as rain, snow, high winds, and other meteorological phenomena. In some cases, though, there is the possibility of predicting when nature will act up so that preparations can be made. Warnings issued by the JMA and relayed by the media, have become essential information, and it is difficult to imagine life without its weather forecasts.

First Steps

The Tokyo Meteorological Observatory in its early days.

The Tokyo Meteorological Observatory in its early days.

The first nationwide weather forecast was made in Japan on June 1, 1884. The curt, imprecise message issued—“Variable winds, changeable, some rain”—was a far cry from today’s in-depth, city-by-city projections. The forecast was written by Erwin Knipping, a German engineer who had arrived in Tokyo in 1871 and was hired as a government advisor in 1881, one of many experts brought to Japan during the Meiji era (1868–1912) to help modernize the country. At the time, meteorology was still a relatively young science, having only gained practicality through the improved communications afforded by the invention and spread of the electric telegraph.

On June 1, 1875, exactly nine years before that first weather forecast, the Tokyo Meteorological Observatory (the forerunner of the JMA) opened. Its location in central Tokyo was far from ideal, as steep slopes surrounded the observation equipment. Nonetheless, it provided a base from which the new science could grow.

In 1883, Knipping began receiving weather reports from around the country via telegraph and prepared the first weather maps. Starting on March 1, the maps were printed and distributed daily. He also launched the first storm warnings that same year.

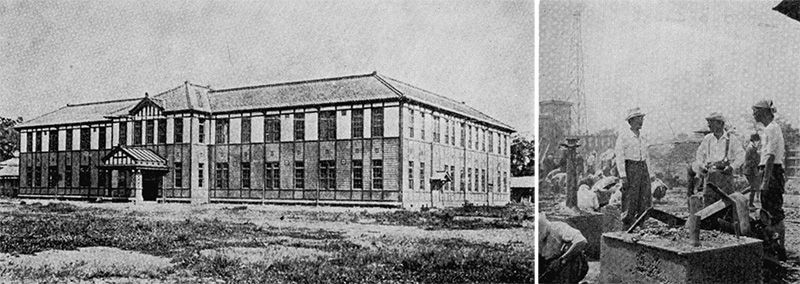

The main building of the Central Meteorological Observatory (formerly the Tokyo Meteorological Observatory) around 1920 (left) and the remains of the Ōtemachi building in Tokyo, which burned down after it was struck by lightning in 1940 (right).

The main building of the Central Meteorological Observatory (formerly the Tokyo Meteorological Observatory) around 1920 (left) and the remains of the Ōtemachi building in Tokyo, which burned down after it was struck by lightning in 1940 (right).

Predicting Rain

A weather observation area at the JMA Tokyo facility.

A weather observation area at the JMA Tokyo facility.

People expect a lot more today from their weather forecasts. In the morning, when wavering over whether to bring along an umbrella, they want to know whether it will rain. Forecasts give the percentage probability of more than one millimeter of rain falling within given period of time, but they do not distinguish between continuous and intermittent precipitation.

Percentage probabilities aside, the weather icons chosen by the JMA provide a straight yes/no answer. In 2013, the agency announced that its accuracy rate for predictions of “rain” or “no rain” was approximately 85% on average nationwide, a roughly 5% increase over the previous 20 years.

The graph below shows the increasing accuracy of Tokyo area forecasts for rain and maximum temperature since 1985.

Tokyo’s “Heat Island”

Along with the improvement in forecasting accuracy, data accumulated through observations has revealed how big cities are heating up more quickly than other areas. Tokyo’s temperature increased by more than three times the world average between 1981 and 2000, according to a report by Yamamoto Akira of the JMA’s Meteorological Research Institute.

This “heat island” phenomenon, where urban areas tend to be significantly warmer than the surroundings areas, is caused by a multitude of factors. Most significantly, the hard, often dark-colored surfaces of buildings and roads in cities absorb and store heat, slowing down overnight cooling. This effect is made worse by the absence of vegetation to bring temperatures down through shade and evaporative cooling, the process whereby plants draw latent heat from the air to evaporate the water taken up through their roots.

The heat island phenomenon is a problem for all major cities, but Tokyo is particularly susceptible, as concrete continues to spread across an ever wider area of the city and parks are few and far between. There are concerns that athletes in the 2020 Olympics will struggle with conditions in late July and early August, when the games will be held. The Tokyo metropolitan government is making some effort to counter warming by adding vegetation and other measures, but this has yet to yield significant results.

Weather forecasts in Japan have become increasingly sophisticated and accurate over the 130 years since Knipping made the first, brief prediction. But there is still a great deal to learn about the way weather systems work and how they are affected by our interactions with the environment.

(Photo courtesy of JMA.)