Revitalizing Rural Japan: the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

More than 500,000 Visitors

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is a spectacularly successful example of energizing regional revitalization with art. Depopulation has enervated vast swaths of the Japanese countryside, and Japan’s national and local governments are undertaking diverse initiatives targeted at revitalizing cities, towns, and villages in nonurban regions of the nation.

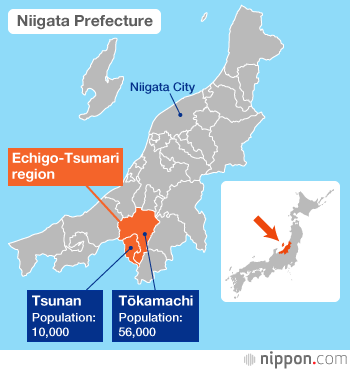

Art festivals bring a distinctively cosmopolitan flavor to the measures for rekindling cultural, economic, and social vitality in the Japanese countryside. Japan’s two biggest regional art festivals are the Setouchi Triennale and the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. The former takes place on 12 islands and at two seaside ports in the Seto Inland Sea, and the latter in southern Niigata Prefecture in the city of Tōkamachi and the town of Tsunan.

The latest of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale took place this year, while the Setouchi Triennale will be held in 2016. Niigata is subject to heavy winter snows, so the organizers of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale schedule it for the summer months. This year’s event, the sixth, opened on July 26 and ran until September 13. It presented some 380 works by artists and teams of artists from 35 nations and regions, drawing more than 500,000 visitors.

The 2015 festival unfolded across 10 sites that comprised about 760 square kilometers. Twice-daily guided tours afforded visitors the option of navigating the expansive grounds in the summer heat aboard air-conditioned buses.

Supplementing the triennale’s appeal for visitors are the scenic attractions of the Tōkamachi Basin. Highlighting those attractions is a breathtaking system of river terraces that snake through a vast canyon.

Hands-On Experience

The triennale’s general director, Kitagawa Fram, characterizes the event as “a place for interchange between people and nature, between cities and the countryside, between the living and the dead, between the familiar and the unfamiliar.”

Kitagawa has headed the event since its inauguration in 2000, striving prodigiously to tug the Japanese public away from urban museums and galleries and out into the countryside. He has proselytized famously for tapping the power of art to invite attention anew to the distinctive identity of different regions.

The triennale has reawakened visitors to the symbiosis with nature that traditionally underlay village life in Japan. It has highlighted, too, the role of craftsmanship in Japanese society. And Kitagawa has worked effectively to foster a sense of solidarity in and among rural communities.

In the official 2015 guidebook, Kitagawa insists that the festival is “more a journey to be experienced than an exhibition merely to be viewed.” A spirit of camaraderie arises between the artists and the members of the community through the process of erecting or installing the works. Elderly residents evince renewed vigor as they watch the work progress. And the young and youngish artists blend into the community during their stay, imparting creative energy through their work.

Kitagawa returns to his “journey” metaphor in describing his hopes for contributing to revitalizing the triennale’s host communities. “This is a journey through time and space via the lifestyles and pastoral symbiosis mediated by the works.” Kitagawa is expressing confidence in the potential for drawing people back to the countryside and for moderating the depopulation and demographic aging that afflict rural Japan.

The attendance figures for 2015 attested to the undertaking’s continuing success in attracting people to the countryside. Among the regular visitors are a growing number of non-Japanese. Before the advent of the triennale, its rural sites rarely figured in the itineraries of foreign visitors to Japan. So the international complexion of the turnout is further evidence of the festival’s value in revitalizing its host communities.

Polka-Dotted Blossoms

A highlight of the event was Kusama Yayoi’s sculpture Tsumari in Bloom. Visitors encountered the polka-dotted blossoms of that work near Tōkamachi’s Matsudai Station.

Also highlighting this year’s festival were evocative works at several former elementary and junior high schools. The works were especially evocative because closed schools—increasingly common throughout Japan—bear witness to the nation’s shrinking and aging population.

Kiyotsukyō Elementary School, which closed in 2009 after 49 years, is one of the schools that metamorphosed for this year’s triennale. Its former gymnasium became an exhibition gallery and a storage warehouse for art works and materials. The onsite storage capacity proved a godsend for urban artists crimped for space and especially for artists who exhibited large works at the festival.

Works displayed in the gymnasium of the shuttered Kiyotsukyō Elementary School.

Works displayed in the gymnasium of the shuttered Kiyotsukyō Elementary School.

Tashima Seizō, a picture book artist, transformed a former elementary school into a “walk-in picture book” for the 2009 triennale. The former Sanada Elementary School, which closed in 2005 after 130 years of service in the village of Hachi, became the Hachi and Seizō Tashima Museum of Picture Book Art. For the 2015 event, Tashima added a work in a former classroom modeled on the school’s last three students and created a biotope outside the museum occupied by the memory-eating goblin Toperatoto and the goat Shizuka.

The Hachi and Seizō Tashima Museum of Picture Book Art by Tashima Seizō.

The Hachi and Seizō Tashima Museum of Picture Book Art by Tashima Seizō.

A focal point of each Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is the Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art/Kinare, a 10-minute walk from Tōkamachi Station. This year, the New York–based Chinese artist Cai Guo-qiang installed a sprawling work through the courtyard and ground-floor corridor. Cai drew inspiration for the work from an island renowned in Chinese legend as the home of immortals. He evoked the island Penglai (“Horai” in Japanese) with trees, a man-made waterfall, and about 1,000 straw objects crafted by children under the guidance of local craftspersons. Cai gave a performance at the museum on July 25, employing his famous technique of creating gunpowder-scorched patterns on paper.

An expansive piece created for the Triennale by Chinese artist Cai Guo-qiang.

An expansive piece created for the Triennale by Chinese artist Cai Guo-qiang.

Cosmopolitan Offerings

Among the numerous works that incorporated natural scenery was Cakra Kul-Kul at Tsumari by Indonesia’s Dadang Christanto. The work comprised an array of bamboo whirligigs atop poles erected along a lane in the village of Seidayama.

Cakra Kul-Kul at Tsumari by Dadang Christanto.

Cakra Kul-Kul at Tsumari by Dadang Christanto.

Theatrical performances were also an important part of the festival. Students from Tokyo University of the Arts and France’s École des Beaux-Arts staged the wordless Nature and Me—Eleven Dreams in Tōkamachi on the night of August 6. The work, performed in a beech forest, employed a diversity of sound effects and lighting to evoke a series of children’s fantasies.

Organizers built a platform near Matsudai Station for the mid-August bon-odori. Obon is the season when Japanese welcome back ancestral spirits and folk dancing known as bon-odori forms a staple of festivities.

Mixed Feelings

Another feature of the triennale was a workshop in which young visitors from abroad gained hands-on experience in traditional Japanese agriculture. Among the participants was a group of youths from Hong Kong.

Young volunteers from Hong Kong have come to Japan to help with the preparations for each triennale since 2006. The youths have welcomed the opportunities that arise during their stays to take part in agricultural work alongside the local farmers. Hong Kong produces only about 7% of the food that its residents consume, so the very notion of cultivating edible produce has been original and stimulating for the visitors. Some of them have even found work in agricultural production on returning to Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, the local residents continue to welcome the festival, albeit with concerns about the fiscal burden that it entails. “This is a pretty quiet place most of the time,” mused a local farmer who was offering free tea and pickled vegetables to tourists near Tōkamachi Station. “So I like the way the triennale livens things up every three years. But I worry about the money that our town budgets for the event.”

The tourism bureau at Tōkamachi reports that the total budget for this year’s event was ¥600 million, with a subsidy from the national government covering ¥230 million of that amount and local tax payers footing ¥100 million. Those figures compare with a total budget of ¥490 million, a government subsidy of ¥100 million, and a local tax bill of ¥100 million for the 2012 event, according to the tourism bureau. The 500,000-plus visitors and the goodwill generated suggest that the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale expenditures have been money well spent.

(Originally written in Japanese by Murakami Naohisa of Nippon.com and published on September 23, 2015. Banner photo: Kusama Yayoi’s Tsumari in Bloom. Photos courtesy of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale Executive Committee)

depopulation Niigata Prefecture art festivals demographic aging rural symbiosis