“Accounts of Huts”: Repercussions of 3/11 in the German Cultural Sphere

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The most radical repercussion from the 3/11 disaster and the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, on an international scale, arguably took place in Germany, where the government decided only a few days after the cataclysm to phase out nuclear power. This radical change in the country’s energy policy was confirmed by the German parliament in June 2011. Beyond this political level, though, there were further reactions that are less easily observed as they are more embedded in everyday culture.

I am not referring here to the direct responses to 3/11, which still continue to this very day. These include the countless solidarity and charity events, the fundraising, the initiatives to house Japanese who wanted to leave their country for a while, and the volunteer visits to Japan by young people (including students of my university) to help rebuild the stricken areas of Tōhoku. Needless to say, there was extensive coverage of the catastrophe in all of the German media, followed by discussion about how to adequately deal with such an event. One TV correspondent was later awarded a coveted media prize for his reports from Japan. There were also impressive, in-depth reports by newspaper journalists who travelled to the affected region to interview farmers, shop owners, mothers, and senior citizens; those who lost their homes and were coping with the hardships of life in temporary housing; and those who returned to their devastated villages.

Media coverage again reached a peak this spring, one year after the disaster. One TV report received particular attention as it impressively illuminated the background to the disappointing and seemingly insufficient information policy- and decision-making of the Japanese authorities, featuring interviews with, among others, former Prime Minister Kan Naoto. This feature was later dubbed in Japanese and posted on YouTube, where by early May 2012 it had attracted more than a million views. During a visit to Japan in late April, I was surprised when my hairstylist told me she had watched this program on YouTube.

Japan in the Print Media—New Perspectives

But what about the wider cultural field? Can we observe any repercussions there beyond the discussion by politicians and academics about the economic, ecological, social, and moral consequences of the nuclear power phase-out, or about disaster reporting and bad journalism?

The German translation of Kamo no Chōmei’s classic text (trans. Nicola Liscutin; Insel Verlag Anton Kippenberg GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, 2011).

The German translation of Kamo no Chōmei’s classic text (trans. Nicola Liscutin; Insel Verlag Anton Kippenberg GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, 2011).

It may sound slightly grim to state that the triple catastrophe in the northeast of Japan has had the effect of reawakening interest in the country again. This was reflected in a noteworthy number of newly published books analyzing the crisis, including reports by persons who were present in Japan at the time it occurred. In addition, the cultural sections of the media addressed issues such as the Japanese mentality, the history of earthquakes in Japan, and the relation of disaster to such characters as Godzilla and Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy). Special editions of weekly news magazines, such as Stern and Der Spiegel, were also dedicated to Japanese history and culture, featuring extensive photograph sections, interviews with prominent Japanese, and numerous articles by journalists and Japan specialists.

In this context, there was special significance in the republication of the German translation of one of the great classics of Japanese literature from the early thirteenth century, Kamo no Chōmei’s Hōjōki (trans. An Account of My Hut), an impressive report and reflection on the natural and social disasters of his time. This work was described by a German critic as uncovering the tension between adherence to the past and consciousness of impermanence. The book, in which a hut is both a place of liberation and self-effacement, impressed its readers with a timeless and fresh approach to the question of how to live in a period of uncertainty and cataclysms.

The issue of the German quarterly journal dedicated to views of the March 11 disaster (ed. Hans-Jürgen Balmes, Jörg Bong, Alexander Roesler, Oliver Vogel, Kazuko Yamaguchi, S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt, 2011).

The issue of the German quarterly journal dedicated to views of the March 11 disaster (ed. Hans-Jürgen Balmes, Jörg Bong, Alexander Roesler, Oliver Vogel, Kazuko Yamaguchi, S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt, 2011).

The spring 2012 edition of the quarterly Neue Rundschau featured German translations of works by 10 different contemporary Japanese authors reflecting on 3/11, including such well-known names as Kawakami Hiromi, Hirano Keiichirō, Kirino Natsuo, Okada Toshiki, and Ōe Kenzaburō, along with reflections by writers and scholars in the humanities on the role of the media. As the editors explained, the project had been planned with the Japanese journal Gunzō prior to the disaster, but in the aftermath of 3/11 it gained particular urgency.

3/11 in German Literature

While it is definitely too early to assess how the disaster will reverberate in German literature, it is worthwhile to note that there are already some examples of remarkably creative approaches. Perhaps the most conspicuous example so far is Das fünfte Buch: Neue Lebensläufe. 402 Geschichten

(The Fifth Book: New Curricula Vitae. 402 Stories), the latest book by writer and filmmaker Alexander Kluge, who celebrated his eightieth birthday in the spring of 2012. With this work, Kluge seems to bring to a close a grand narrative project he began 50 years ago with a cycle of collections of “life stories.” As the author explains: “Our curricula vitae are houses from the windows of which we humans interpret the world: a vessel of experience for that which can be narrated in a literary fashion.”

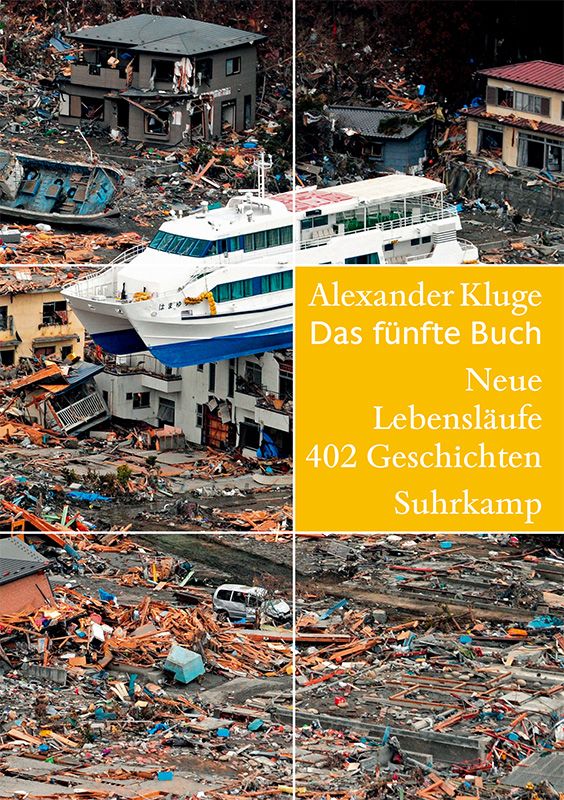

Alexander Kluge’s most recent book takes a more creative approach to addressing catastrophe (Suhrkamp Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, 2012).

Alexander Kluge’s most recent book takes a more creative approach to addressing catastrophe (Suhrkamp Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, 2012).

The slipcase of the 564-page book shows the emblematic photo of a large ship stranded on top of a house in the midst of the devastation and debris of the 3/11 tsunami. The first chapter includes a complex mixture of invented and real stories, reflections, and essays on diverse topics, such as an eighteenth century French novel and meetings with famous historical personalities. It also contains a subchapter titled “Age-Old Friends of Atomic Energy” in which Kluge presents anecdotes from experts on the Fukushima nuclear accident, interwoven with reports of research on extraterrestrial disaster shelters for future mankind or on earthquakes and tsunami in antiquity.

Kluge, who narrowly survived an air raid in World War II, is driven by the leitmotif of having survived by mere chance. Thus, as one reviewer remarked, it is not the search for truth or passion which motivates his protagonists, but issues of self-respect, self-preservation, and professionalism. Kluge also wrote the script for a radio drama, broadcast this April, on the topic of extreme catastrophic experiences, in the vein of his larger work, Das fünfte Buch. This much-praised book is just one example—or just one “account of a hut,” if you will—of how the crisis in Japan is reflected in German literature, and we can be sure that we will see more in the months and years to come.

Overall, it seems safe to say that the disaster in the northeast of Japan has shaken the German psyche much more deeply than the 2004 tsunami disaster in Southeast Asia. A disaster occurring in a highly industrialized nation like Japan made people in Germany feel the limits of control, technology, and progress, triggering reflections on a fundamental and philosophical level. Germans were made aware of the fragility of all our existences, and this shock seems to have connected us even more closely with the people in Japan.

(Originally written in English on June 13, 2012.)