Reforming Japan’s Electricity System

Politics Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

As part of the process of formulating a new set of basic principles for the nation’s energy policy, an Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy has been appointed to report to the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. I am chairman of the Specialist Committee for Electricity System Reform that is a part of this project. Our job is to consider the shape that Japan’s electricity system should take in the years to come. In this article I want to give a brief account of the overall direction these reforms are likely to take.

The Need for Reform

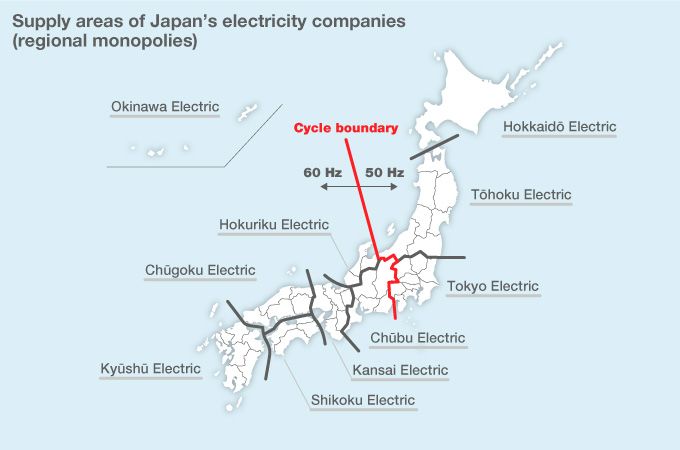

The disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station marks a historical turning point for Japan’s energy policy. One of the results will be fundamental and wide-ranging reform of Japan’s electricity system from the roots up. Before the accident, the electricity business in Japan was divided among ten regional electricity companies, each of which enjoyed a virtual monopoly over all aspects of electricity within its region, from generation to transmission, distribution, and retail.

Around the world there is a trend toward deregulation of electricity. Deregulation normally hinges on two key concepts: separating the generation and transmission functions of the electricity business, and liberalization at the retail and wholesale level. Japan has implemented a number of policies along these lines in recent years. But these reforms failed to go far enough, and as a result the regional utilities continued to enjoy quasi-monopolies within their areas of responsibility.

Some of the effects we can expect to see from a thoroughgoing reform of the electricity system are as follows.

- Broader competition between regional utility companies and new entrants to the market. This should lead to cheaper prices and improved services.

- The establishment of an independent electricity grid that can be used by all companies should help to encourage wider use of renewable energy.

- Liberalization at the retail level will encourage increased use of energy-saving technology and distributed generation. It will also improve demand response mechanisms(*1), allowing the system to respond more flexibly to fluctuations in supply.

To help readers understand the import of these reforms, it may be useful to review some of the problems that beset Japan’s electricity system in the past.

Source: Report of the METI Specialist Committee for Electricity System Reform. (July 2012, available only in Japanese.)

The Lack of a National Grid

Until the disaster in Fukushima, Japan had been deliberately increasing its dependence on nuclear power. In terms of energy security and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, nuclear power seemed an attractive option. With the single exception of the Okinawa Electric Power Company, all the regional utilities were positive about developing nuclear power. Nuclear power stations were built to ensure a stable supply of electricity in response to increasing demand, and dense distribution grids were set up to bring electricity from the nuclear power stations to the various regions.

However, as noted above, each utility company exerted a monopoly over all supply functions within its area of control. As a result, each company ended up developing its own distribution grid. Under this approach, the priority was to achieve a stable supply model for each region. Building a superregional network was not particularly important. This led to perhaps the greatest weakness in the system: inadequate integration of the regional grids into a nationwide network. In particular, the electricity supplies of east and west Japan operated on different cycles, making the links between Japan’s two major industrial centers extremely weak. Even between regions using the same cycle, connectivity was often difficult—the link between Hokkaidō and the main island of Honshū is one example.

In a sense, it was the lack of any urgent need to trade electricity between regions that allowed these conditions to remain unchanged for so long. As a result, the utility companies’ regional monopolies were preserved intact. There was no competition between them, and it became almost impossible for newcomers to enter the market.

From Stable Supply to Demand Response

The basic orientation of Japan’s energy policy from now on will be to reduce the country’s dependence on nuclear power. The debate continues about the speed at which this will be achieved. But whatever the timetable, one thing is certain: Japan will dramatically reduce the extent to which it relies on nuclear power for its energy needs.

But it was the widespread use of nuclear power that allowed Japan to secure a stable electricity supply until now. Expanding demand has been met by building new power stations, increasing capacity, and improving technology in existing plants. Now, we urgently need to change our approach and come up with a new way of guaranteeing a stable supply of electricity for the future. This will require us to abandon the demand-led model that has prevailed until now. We need a new approach—one calibrated to demand and capable of bringing demand into line with a fluctuating supply.

In particular, we need a framework for limiting peak demand, efforts to promote energy-saving technology, and a way of dealing with the instability of supply inherent in renewable energy.

Liberalizing electricity retailing and encouraging the uptake of smart meters will be important in developing the kind of demand-side responsiveness we need. In the future, smart meters should make precisely incremented billing and discounting possible. The involvement of competing companies should lead to the introduction of demand response programs.

Getting More Companies Involved

Separating electricity generation from transmission and establishing a national grid with independent and transparent billing would make the grid independent of the existing system of regional monopolies. This would encourage newcomers to join the industry. The involvement of a wider range of companies in electricity generation and distribution should help to bring about investment in more efficient energy generation.

Increasing dependence on nuclear power meant that Japan failed to invest sufficiently in thermal power, with the result that many of Japan’s thermal power generation facilities are in a poor state of repair.

The idea would be for newcomers to the market to invest not only in large-scale generation but in cogeneration (in which the heat generated during electricity generation is put to practical use) and other forms of distributed generation. Getting gas and oil companies actively involved in the electricity business would also make it possible to integrate electricity generation into the energy industry as a whole.

Another aim of reforms to separate the generation and distribution functions of the electricity business is to widen the distribution grid. I said earlier that poor connectively between regions was a major weakness of the Japanese electricity system. Solving this problem will be the first step toward reforming the system.

Broader integration of the electricity grid should help to encourage superregional competition between electricity companies. Additionally, in order to increase the use of renewable energy, we need to ensure that electricity is supplied and consumed across a wider area than in the past. Long-range electricity trading will alleviate the instability of supply that is one of the drawbacks of renewable energy. It would also open up the possibility for electricity generated by wind power in Hokkaidō to be used in Tokyo, for example.

(Originally written in Japanese on August 19, 2012. For more information on Japan’s energy situation, see our in-depth series, "Energy Policy: Japan at the Crossroads.")

(*1) ^ In electricity grids, demand response mechanisms manage customer consumption of electricity in response to supply conditions, for example, by having electricity customers reduce their consumption at critical times or in response to market prices.—Ed.

nuclear power energy policy reform energy Itoh Motoshige electricity companies liberalization