Scarecrows Stand Watch over Village on Borrowed Time

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

At first glance, they look much like people, and the village seems to be full of residents going about their daily business. These particular locals are not people, though, but scarecrows. The mannequins outnumber the village’s 40 or so human residents by more than two to one, and on the surface—with their own distinctive personalities—do create a rather cheerful atmosphere. But in the context of a Japan suffering from population decline that puts rural communities like this one in danger of disappearing altogether, the spectacle takes on an altogether more eerie aspect.

A Whole Community of Scarecrows

The village of Nagoro, Tokushima Prefecture.

The village of Nagoro, Tokushima Prefecture.

The home of these scarecrows is the tiny mountain hamlet of Nagoro, near the town of Miyoshi in Tokushima Prefecture. Because of the proximity to the heavens that stems from Nagoro’s 800-meter altitude, the village is also sometimes referred to as Tenkū no Sato, literally “home of the sky.” Nestling in the belt of rural mountain settlements at the heart of Shikoku’s main island, it takes three hours to reach the village by car from the city of Tokushima itself. In fact, Nagoro is even deeper in the mountains than the areas where remnants of the defeated Taira clan are said to have taken refuge following the Genpei War (1180–85).

But this isolated settlement recently became the focus of international attention after it was featured in a short documentary posted online in spring 2014. The video by Fritz Schumann, a young German photojournalist studying in Hiroshima, has already received nearly half a million views.

Creator of Nagoro’s scarecrows, local resident Ayano Tsukimi.

Creator of Nagoro’s scarecrows, local resident Ayano Tsukimi.

These suddenly world-renowned scarecrows are the work of Nagoro native Ayano Tsukimi (64), who resides in the village with her elderly father, having returned to her home town 12 years ago following a period spent living in Osaka. She recalls how it all started: “After I came back, I tried to sow some seeds in the fields around here, but nothing would grow. So I decided to try making a scarecrow.” More than a decade later, what started out simply as a way to keep wild animals away from the fields has since repopulated the entire village with mannequins.

Ayano starts each piece by fashioning a richly expressive face. Next, she wraps a wooden frame in more than 80 sheets of newspaper to make the torso. To finish off her creations, she dresses them in old clothes, boots, and sneakers.

On average, a single mannequin takes around two days to complete, but as they are placed outside or in the fields, Ayano says her creations tend not to last more than a couple years. Of the more than 350 scarecrows she has produced to date, there are currently 100 or so dotted around the village.

A Wealth of Characters on Display

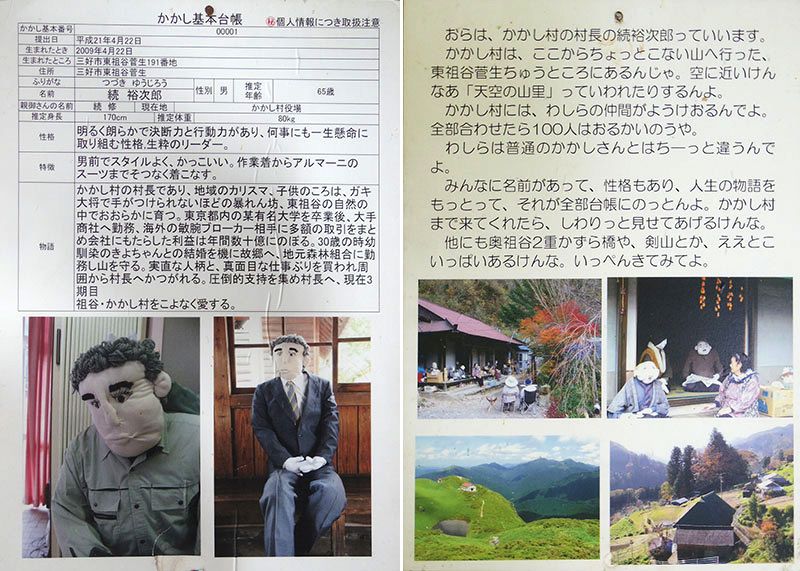

The Scarecrows’ General Ledger, which includes biographical information for all of Ayano’s creations, including “Mayor” Tsuzuki Yūjirō (pictured).

The Scarecrows’ General Ledger, which includes biographical information for all of Ayano’s creations, including “Mayor” Tsuzuki Yūjirō (pictured).

One of Nagoro’s particularly amusing quirks is the Scarecrows’ General Ledger, which is kept in the rest area near Ayano’s house, where visitors can read it. A notice nearby reads: “We are not like normal scarecrows. We each have our own names, our own personalities, and life stories—all of which are written in this book.”

Top dog in the village is mayor of the scarecrows, 68-year-old Tsuzuki Yūjirō, whom the ledger describes as now possessed of a steady, earnest disposition, despite being the toughest kid in his grade in his school days. After graduating from “a famous university” he started work at “a big company,” coming back to his hometown at the age of 30 to marry his old childhood playmate, Kiyo. Currently in his third term as mayor, Tsuzuki also apparently helps to protect the mountain as a member of the local forestry commission. Tsuzuki’s scarecrow can be seen wearing a navy blue Armani power suit with big shoulder pads. His profile describes how he always effortlessly pulls off the look, whether he’s wearing work clothes or an expensive suit.

More Ahead for Creator

At present, Ayano makes the long drive to Tokushima once a month to lead a workshop in scarecrow making. And every month, she is kept company on the round trip by the mannequin of a young man sitting attentively in the passenger seat of her trusty old car.

Although she chats enthusiastically in our interview about how the scarecrows have helped her meet all sorts of people and insists she intends to keep on making them as long as she is able, Ayano offers no further explanation of the deeper whys and wherefores than “I just do it for a hobby.” But thanks to her creations, the local villagers have been able to welcome many visitors to the area.

According to Ayano, the youngest residents of Nagoro are two junior high school students, while the majority of the remaining villagers are steadily advancing in years.

The Stark Reality of Genkai Shūraku

In Japan, communities are called genkai shūraku, literally “settlements at their limit,” when their ability to function as a community and even their very survival are threatened by population decline and aging. According to a recent report by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, as of April 2013 there were over 10,000 such settlements scattered across Japan.

On the day we visited to conduct our interview, it was raining heavily. In the whole time we were there we only actually saw one resident. In an hour and a half on the surrounding roads, we passed no other cars save for three small trucks. In such a lonely setting, there was something rather mysterious about all the funny scarecrows sat out, soaking, in the rain—along with a sense of pity that made us want to lend them an umbrella.

But what would it be like to happen across these figures in the middle of a pitch-black night? Your heart would certainly skip a beat, even if you had expected the scarecrows to be there. The terror of a silent place, far from other people, drills home the severity of the situation facing the nation’s genkai shūraku.

The Huffington Post recently described Nagoro as an “abandoned Japanese village.” In a society where low birth rates and graying heads are contributing to rapid declines in local populations, the day may not be all that far off when even a community as idyllic as this becomes a ghost town, home only to the scarecrows.

(Originally written in Japanese)

art aging society Tokushima Shikoku population decline outsider dolls