Approaching the Seventieth Anniversary of the End of the War

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

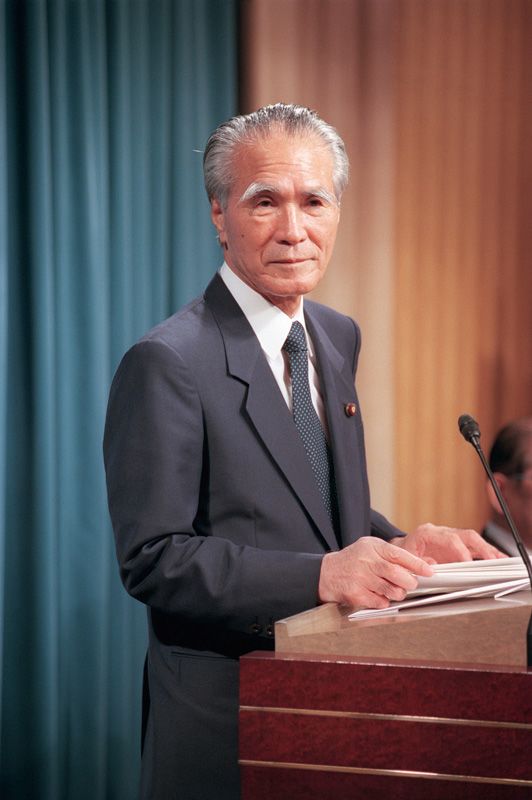

What does the New Year have in store for Japan? One major event in 2015 will be the seventieth anniversary of the end of the World War II, the sort of symbolic occasion on which grand statements are expected from government and parliament alike. In 1995, marking 50 years since the end of the war, Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi made a statement in which he apologized for the country’s past aggression, calling Japan’s wars a “mistaken national policy.” The statement received wide acknowledgment all over the world and has been upheld by almost every Japanese government since.

In 1995, Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi made what is seen by many as the definitive Japanese statement on the country’s wartime past. (© Jiji Press)

In 1995, Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi made what is seen by many as the definitive Japanese statement on the country’s wartime past. (© Jiji Press)

Soon after he came to power in late 2012, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō announced his intention to replace the Murayama declaration with a new statement to be issued on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the end of the war.(*1) He has since given clues as to what the content of this statement might be, explaining that there is no generally accepted definition of aggression (at least none that he would accept) and, thus, his doubts as to whether Japan fought a war of aggression.(*2) He has also emphasized several times that he doubts whether Japanese state authorities were directly involved in the recruitment of so-called comfort women for use by the Japanese military during the war. All of this has brought him a reputation as a historical revisionist, negatively influencing the image of Japan worldwide and damaging the country’s position as a trusted member of the international community.

European Consensus on the War

This year, in spring and summer respectively, the anniversaries of the end of the war in Europe and East Asia will attract the attention of the global media. But few media representatives and politicians in Europe at this point seem to have given much thought to the upcoming anniversary in May. What is the reason for this low general awareness? Although some commemorative ceremonies are scheduled, in Europe there are no major controversies about the war. There are no attempts to alter mainstream interpretations of the conflict, or even the rather one-sided judgments of the Nuremberg trials, in which German officials were tried as war criminals.

Although there are those with misgivings about the legitimacy of aerial bombardments of German cities and the postwar expulsion of Germans from Eastern Europe, there is no debate as to whether or not the Axis powers—Japan, Germany, and Italy—were guilty of waging a war of aggression. That particular issue is one that is universally considered to be clear-cut, given the fact that these three powers all attacked other countries without any prior military provocation, in some cases without even a declaration of war. Most of these unprovoked attacks were led by Germany (on Poland, Denmark, Norway, and the Soviet Union—all without a declaration of war), but Italy (Ethiopia, Albania) and Japan (China, British Malaya, the United States, and the Dutch East Indies) also played their part in the global escalation of hostilities. None of the Axis powers were ever unilaterally attacked by any other country.

In Europe, the most important lesson taken from the war is that in the future such conflicts need to be avoided at all costs. To that end, European governments routinely uphold their predecessors’ statements about the war, even though individual officials might not agree entirely with the underlying historical interpretation. Placing the greater good over one’s personal opinions when it comes to such matters is considered by most to be a very small price to pay for peace and stability in Europe.

Abe’s Family Affair

In East Asia, the situation is different. The complicity of Prime Minister Abe’s grandfather Kishi Nobusuke (1896–1987) in the policies of the wartime cabinet of Tōjō Hideki (1884–1948), in which he served as deputy minister of munitions from 1941 to the end of the war, makes Abe see history in a different light—as an individual, unable to keep his family business separate from his official duties. Abe is also guilty at times of not following his own advice. Although he has stated in the past that “the judgment about history should be left to historians,” he frequently rejects the historical consensus and tries to “set the record straight,” often based on the advice of individuals with no academic credentials.

Two-year-old Abe Shinzō (left) plays with grandfather (then Prime Minister) Kishi Nobusuke and older brother Hironobu in 1956. (© Mainichi Shimbun/Aflo)

Two-year-old Abe Shinzō (left) plays with grandfather (then Prime Minister) Kishi Nobusuke and older brother Hironobu in 1956. (© Mainichi Shimbun/Aflo)

Because of his family background, Abe has been at the center of what some have dubbed a movement for historical revisionism, beginning with his involvement in the LDP’s internal Committee for the Investigation of History (Rekishi Kentō Iinkai, 1993–95). For the sake of peace and stability in East Asia, it has to be hoped that he will, in 2015, put his narrow personal agenda behind the greater good of Japan and not further damage this country’s image in the world with provocative statements regarding Japan’s role in the war. If “harmony” (和, wa) is truly the strength of the Japanese people, then “reconciliation” (和解, wakai) with former enemies should not be such a difficult task to achieve 70 years after the end of the war.

(Originally written in English on January 5, 2015. Banner Image: The emperor and empress pay their respects at a war memorial service in Tokyo, August 15, 2014. © Jiji Press.)

(*1) ^ See, for example, the interview with Abe in the Sankei Shimbun, December 30, 2012.

(*2) ^ See the collection of “Analects” on his website (Japanese only).

Abe Saaler Sven World War II war Murayama seventieth anniversary