Teresa Teng: An Asian Idol Loved in Japan

Politics Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

As Popular As Ever

Last year marked the twentieth anniversary of the death of Teresa Teng, an Asian pop legend who won fame in Japan with a string of hits. Teng was only 42 when she suffered a fatal asthma attack in 1995 while at a holiday resort in Chiang Mai, Thailand. In Japan her songs remain as popular as ever on karaoke rankings and almost 3 million of her CDs and DVDs have been sold in the country since she passed away. It is rare for the Japanese to show such enduring affection for a foreign singer and this cannot be due simply to her remarkable voice and angelic appearance.

Photograph courtesy of Universal Music Japan.

Photograph courtesy of Universal Music Japan.

Teng’s mother loved music. From early childhood the star learned traditional Chinese songs, which is perhaps why she understood so well the importance of lyrics. In China, song lyrics (ci) were once looked down on as a lower form than poetry (shi). But in the Song Dynasty (960–1279), exemplary works by noted writers helped develop them into a recognized literary genre.

Teng’s 1983 album Dandan youqing (Light Exquisite Feeling) is a magnificent example of Song Dynasty lyrics set to contemporary melodies. Teng delivers laments on the nature of life and odes of longing for home inscribed by ancient literati, releasing a flood of emotion that transcends time and space.

Connecting Japan with Asian Neighbors

When she sang Japanese songs too, Teng paid close attention to the lyrics. With the help of interpreters, she repeatedly asked songwriters and producers the meaning of different words and would not proceed to the recording booth until she was satisfied she understood them fully. While performing, she captured the hearts of her fans by imbuing each word with meaning as she carefully sang them to the melody so that it seemed to her listeners that she was speaking directly to each of them.

As well as her own hits, Teng covered Japanese kayōkyoku pop songs translated into Chinese. She recorded many of these while living in Los Angeles in 1980. These were later distributed on cassette and CD in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China as well as Southeast Asia, becoming widely known throughout the region.

In 2002, Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō sang the Japanese ballad “Kitaguni no haru” (Spring in the North) together with members of the Vietnamese government at a banquet during his visit to the country. This received considerable attention from the local media, but Koizumi’s singing skills only succeeded in stirring up so much interest due to Teng’s popularization of kayōkyoku in Southeast Asia. I myself have felt the benefit of this popularization, having deepened friendships with people around Asia through singing Japanese songs together at karaoke sessions everywhere from Taiwan and China to Vietnam and Cambodia.

Complex Identity

Teng’s words and actions also made people in Japan think about the diversity of Asia and the Sinosphere in particular.

Her Japanese debut came in 1974, two years after Japan severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan in order to normalize relations with the People’s Republic of China. Already a big name in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia, Teng may have wanted to break through in Japan, the region’s largest and most developed market, to ensure she could make the subsequent leap to the global stage. For the general public in Japan, however, she started as just one of many unknown Asian singers drawn to the country by its promise of greater celebrity.

Teng had established herself in Japan when she was deported in 1979 for entering the country on an Indonesian passport. She was subsequently banned from returning for a year. At the time many Japanese people did not know the tough situation Taiwan was in due to its lack of diplomatic recognition.

As China reformed and opened up to the world in the post-Mao era, Teng’s fame spread throughout the country. Her surname was written with the same character as new leader Deng Xiaoping, and by around 1982 there was a common saying that in China people listened to “old Deng” by day and “little Teng” at night. Not everyone supported her rise though. A campaign by senior cadres against “spiritual pollution” singled out her song “Heri jun zailai” (When Will You Return?) for particular criticism. Hearing this kind of news changed Japanese perceptions of its near neighbors and gradually focused attention on Teng’s complex sense of identity.

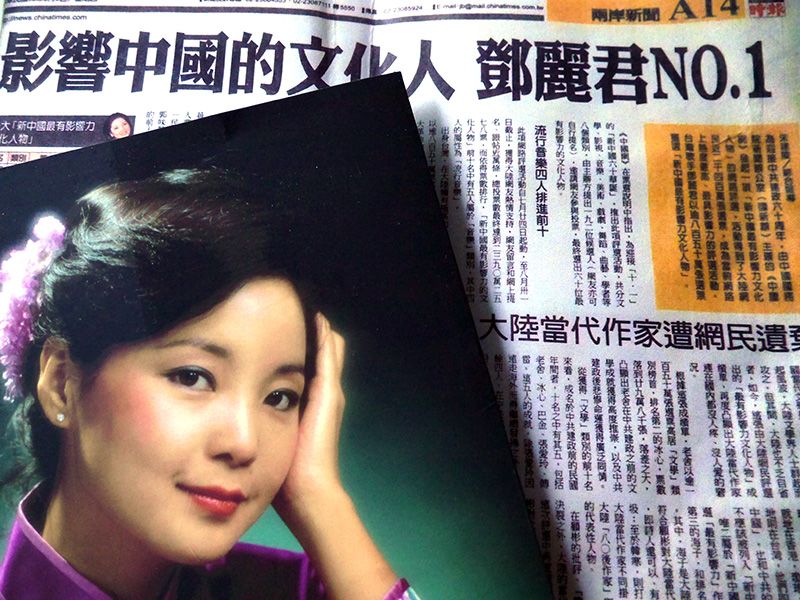

The most influential entertainer in China. Photograph provided by the author.

The most influential entertainer in China. Photograph provided by the author.

Tiananmen Incident Halts Plans for China Concert

In 1984, Teng relaunched her career in Japan and had hits with “Tsugunai” (Atonement), “Aijin” (Lover), “Toki no nagare ni mi o makase” (Give Yourself to the Flow of Time), and “Wakare no yokan” (Premonition of Parting) between 1984 and 1987. She also won the Japan Cable Award Grand Prix for three successive years. In 1985, she achieved her dream of performing on the NHK New Year’s eve song contest Kōhaku uta gassen.

Just as she was approaching the summit of the entertainment business in Japan, Teng quit all of her other activities to focus on recording. Her younger brother Teng Chang-hsi said that this was because of her “fatigue after being in the entertainment world for so long,” but a huge influx of royalties from Japan also allowed her to think about what she really wanted to do. One plan was to give a concert in mainland China, where her parents were born, but this was shelved following the brutal suppression of Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests in 1989. Teng quickly shifted her base of operations from Hong Kong to Paris.

New Role as “Overseas Chinese”

In 1991, I had the chance to speak to Teng while she was living in Paris. I remember her telling me that her move was not an escape, but preparation for “returning one day to a democratic China.”

Along with many others, Teng’s parents fled to Taiwan after Kuomintang forces were defeated in the Chinese Civil War. She struggled for a long time with questions of identity, feeling caught between the country of her birth and that of her ancestors. When she lived in France though, she seemed to fit into a new role as an “overseas Chinese,” defining herself in terms of traditional Chinese culture rather than nationality. She continued to dream of performing in a charity concert in Tiananmen Square at some future date and talked of how she was training her voice and studying composition, as well as how she was inspired by new music.

In 1993, she returned to Japan after a long absence. During her visit she appeared on television, saying, “I am Chinese. Wherever I live, wherever I am around the world, I am Chinese.” It seemed that the Japanese got a glimpse of how the people of China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong—along with the many overseas Chinese scattered across the globe—feel at heart. Perhaps her words were directed particularly at those Chinese fans who filled Tiananmen Square in 1989.

For Japanese, Teresa Teng was more than just a popular singer. By performing kayōkyoku, she connected Japan to its Asian neighbors. She taught us about the profundity of Chinese culture, whether in her birthplace of Taiwan, her ancestral home of China, or Hong Kong, which she loved throughout her life. We, her Japanese fans, will never forget her velvety voice and the brief, beautiful radiance of her life.

(Originally written in Japanese on May 28, 2015, and published on June 15, 2015. Banner photo courtesy of Universal Music Japan.)China Taiwan Hong Kong entertainment Teresa Teng overseas Chinese singer