Coffee and Identity at Starbucks Japan: A Matter of Culture

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In his witty article “The Name on My Coffee Cup,” published in the New Yorker, Saïd Sayrafiezadeh describes how his name is systematically misspelled when ordering coffee at American Starbucks—“Zal,” “Sowl,” “Sagi,” “Shi.” In the United States, Starbucks employees write down your name on the coffee cup. I had never given thought to this before—every time I went to Starbucks in Seattle or Los Angeles or San Diego my name “Pablo” appeared written down correctly on the cup. But Japanese etiquette dictates that Starbucks customers be called by the items they order, not their names. Here in Japan, you are “the customer who ordered a tall latte” or “the Frappuccino customer.”

Which makes sense. Let’s say that baristas write down the name of a Japanese customer on the cup: Tanaka, or Suzuki, for example. There could be any number of Tanakas or Suzukis waiting in line, and this could lead to confusion. (In everyday life Japanese are referred to by last name.) Furthermore, privacy is a delicate issue. Most people would not be happy about having to reveal their names in public. For cultural reasons, soliciting customers’ names when they order coffee would probably not be well received in the Japanese archipelago.

You may think the Japanese are stiff about such social norms, but Japan isn’t alone in its discomfort with excessive casualness. A 2012 BBC News article, “Will you tell Starbucks your name?” argued that Britons would find it awkward to be treated in a too-casual tone at the coffee shop. All they want is their drink; for them, Starbucks is no social club.

The Difficulty of the Name Game

Whatever the reasoning for it, baristas treat you neutrally at Starbucks Japan by calling you through your order, not your name. This is perhaps a blessing for foreigners. It’s not uncommon for Japanese people to misunderstand foreign names. Usually, words not native to Japan are transliterated using a syllabic alphabet known as katakana. Alien words are converted into sounds that Japanese can recognize: non-Japanese sounds are Japanized. This practice has been the source of bizarre anecdotes too numerous to detail here. Let it suffice to say that some foreign names are transliterated quite decently while less fortunate ones can become horribly crippled.

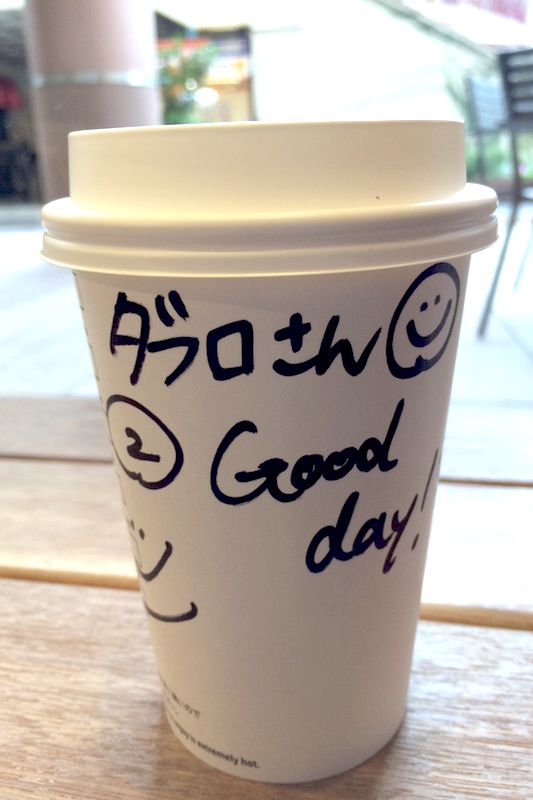

An attempt to get a Japanese barista to use the American name-writing style results in a friendly greeting—and a mangled name, Taburo.

An attempt to get a Japanese barista to use the American name-writing style results in a friendly greeting—and a mangled name, Taburo.

There has been one circumstance over the years in which I was always asked for my name. Every time I took film to develop, the clerk would solicit my name and phone number. In my case, although the Spanish name Pablo is relatively easy to pronounce in its katakana version, Paburo, I’ve found that clerks can be very good at not understanding it. Why this happens remains a mystery. It’s not that I mispronounce it; I know for a fact that there is no trace of an accent when I say it in Japanese. It’s more like some people are very talented at deforming it.

I vividly remember one particular occasion when the clerk at a large camera chain in the Tokyo neighborhood of Shinjuku asked my name when I took a roll of film to develop. “Paburo,” I confidently answered pronouncing the sounds that constitute the Japanese version of my name.

“Pabelo?” he asked, somewhat confused.

“Pa-bu-ro,” I patiently replied.

“Pabaro?” came the second reply. I thought I might have not vocalized the syllables properly, so I proceeded to repeat myself, this time very carefully, with modulated sounds. Pa. Bu. Ro.

“Babro? Oh, I get it, Babelo!” he said with an explosive laugh, clapping his hands.

Ways to Avoid Confusion

Years ago this used to upset me. I tried different strategies to avoid obnoxious misunderstandings. When asked, I changed my name to Peter or John. Sometimes I said my name was Tanaka (which confounded clerks even more: virtually nobody in Japan will believe you can carry a Japanese name if your face looks Western). However, even when these stratagems worked, I wasn’t fully comfortable with having to produce a name I did not have. So I started writing it down for them, in katakana, which proved efficient. I also discovered that people would understand the name Pablo more easily with a famous association: “Pablo, as in Pablo Picasso.” This had the benefit of adding an artsy touch to my identity, which I found enormously satisfying.

These days I don’t care too much about whether my name is understood properly, which is liberating. And there aren’t that many public instances when a name is requested. If it’s necessary, you are generally asked to fill out a form, for example when you order something for delivery, and employees can read your name from there. So it’s not a problem.

At any rate, I remain a regular Starbucks customer, and things work out pretty well most of the time. I can’t imagine that the practice of writing people’s names on Starbucks cups is going to pick up in Japan anytime soon. But who knows? With booming tourism, some parts of Tokyo are becoming more international, to the point where you may walk into a Starbucks in Shinjuku and find a non-Japanese taking your order at the register, something unthinkable until not long ago. The day may even come when people will be able to place their Starbucks coffee orders through their smartphones, pay electronically, and pick up the drink at an express counter without having to talk to the clerk at all. If this happens, numbers would probably do better than names.

For now, though, I still enjoy human interaction at Starbucks the Japanese way. Just call me “the Venti latte customer.”

(Originally published in English. Banner photo courtesy Sekido Ryōsuke.)