Shifting the Employment Debate: “Nonregular” Focus Distracts and Misleads

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nonregular employment is now said to account for around 40% of all jobs in Japan. There is a huge gulf in conditions between regular employees (seishain) and nonregular employees (hi-seishain). In a bid to eliminate this gulf, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō pledged to bring about “equal pay for equal work” in his January 2016 policy speech.

Closing the gap will not be an easy task, however. Companies that are pressured to boost the pay of nonregular employees will not wish to increase their wage bills. At the same time, labor unions and other worker representatives are resistant to any moves that would downgrade regular employees’ conditions to bring them in line with those of nonregular employees. While everyone agrees in general with equal conditions, specific approaches foment outpourings of opposition.

A Recent Focus on Forms of Employment

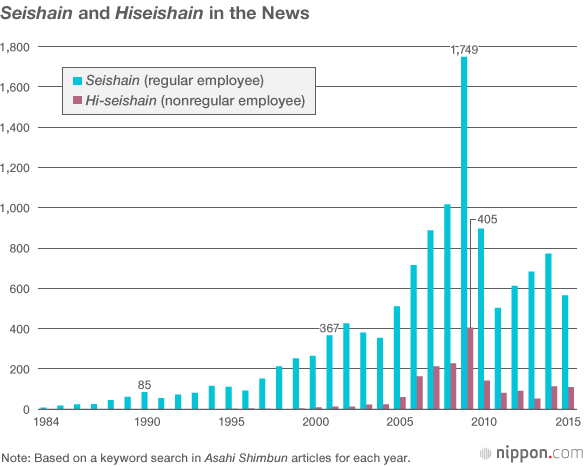

It seems that not a day goes by without encountering the words seishain and hi-seishain in the newspapers and other media. How long has there been this intense focus on the two different forms of employment? The chart below shows the number of articles that mention seishain and hi-seishain in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, based on a keyword search. Last year the word for regular employees appeared in 565 stories and the word for nonregular employees in 110. Seishain was used in more than 300 stories for the first time in 2001, but never appeared more than 100 times until 1994.

The word hi-seishain, by contrast, almost never appears in articles until the mid-1990s. Even as recently as 2004, there were only 24 stories, or two per month on average.

Both achieved a sudden ubiquity in 2009, the year after the financial crisis originating in the United States spread around the world. The chart shows that seishain was in 1,749 Asahi Shimbun articles in 2009, an average of 4.8 every day. Hi-seishain appeared almost every day too. The immediate cause was the establishment on December 31, 2008, of a tent village in central Tokyo’s Hibiya Park for day laborers who had become homeless after being laid off. Although the village was soon closed down, it inspired much public interest in employment issues.

Until then, different kinds of employment were generally only discussed in government statistics and papers written by specialists, and received little attention in ordinary everyday life. It is surprisingly recently that people in Japan have come to talk about regular and nonregular employees as a matter of course.

No Legal Definition

While there is a new spotlight on regular and nonregular employees, it is also important to note that there is no clear definition of what a seishain actually is.

It may be surprising to learn that there is no mention of regular employees in Japanese employment laws. The word seishain carries a vague image of a full-time worker required to flexibly carry out a range of duties in various locations, who is thereby guaranteed long-term employment. Yet, there are no legal standards to say what “long-term” means or how much “flexibility” is required. For this reason, seishain cannot be defined in legal terms.

So what does it mean to say around 40% of employment is “nonregular?” This ambiguous figure, derived from government statistics, is simply based on whether employers describe their workers as regular or nonregular. People doing the same kind of jobs may be called seishain at one workplace and hi-seishain at another.

There is a strong association between hi-seishain and unskilled laborers, but most of these people work extremely hard day in, day out, in tough conditions, and it is an affront to their dignity to say that they are not “regular employees.” We should no longer give legitimacy to only part of the workforce as seishain and regard the rest as “nonregular.”

Focus Should Be on Contract Duration

What would be the best replacements for these terms? Describing jobs according to contract duration would be most appropriate, as in permanent (muki koyō) or fixed-term (yūki koyō) employment. Under the Labor Standards Act, it is mandatory to make the employment contract period clear on contract documents, along with the salary, place of employment, duties, work hours, days off, and matters related to leaving the position. In addition to stating whether the contract is permanent or fixed-term, in the latter case it is necessary to include how long the contract will be, whether it can be renewed, and if so, what the requirements for renewal are.

In principle, fixed contracts have a maximum length of three years. If employees who have been working under contract for more than five years request permanent jobs, their employers are obliged to comply. Exceptionally, however, five-year contracts are allowed in the case of highly skilled positions that are often filled by foreign professionals. In this case, the switch to permanent employment on request only becomes mandatory after 10 years.

The Labor Contract Act clearly sets out matters related to dismissal of workers on fixed-term contracts. These employees cannot be dismissed until the expiration of the contract, barring the presence of unavoidable circumstances. The act also states that employers should not make contracts unnecessarily short, to avoid overly frequent renewal.

Many “nonregular” employees are on fixed-term contracts, but this does not mean they can be legally dismissed at will. Some people also believe that employers are free to simply let workers go when they complete their contracts, but this is not true either.

Employers are actually required to provide advance notice if they do not plan to renew a worker’s contract, and to make the reason for dismissal clear if requested to do so. The 2013 amendment to the Labor Contract Act also incorporated the principle, based on Supreme Court precedents, that employees cannot be dismissed without objectively reasonable grounds and if the dismissal is not in line with socially accepted principles.

If more people started thinking in terms of fixed-term rather than nonregular employment, it would certainly encourage a correct understanding of employment rules.

Some “Nonregular Employees” on Permanent Contracts

The table below gives the numbers and percentages of regular and nonregular employees—the latter divided into various categories based on the terms in use at each company—on permanent and fixed-term contracts.(*1)

(Millions of people)

| Total | Permanent Contract | Fixed-term Contract | Don’t Know | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 53.54 (100%) | 36.70 (69%) | 12.12 (23%) | 4.45 (8%) | |

| Seishain (regular employees) | 33.11 (100%) | 30.54 (92%) | 1.35 (4%) | 1.21 (4%) | |

| Hi-seishain (nonregular employees) | 20.43 (100%) | 6.16 (30%) | 10.76 (53%) | 3.23 (16%) | |

| Pāto | 9.56 (100%) | 3.71 (39%) | 4.38 (46%) | 1.35 (14%) | |

| Arubaito | 4.39 (100%) | 1.57 (36%) | 1.49 (34%) | 1.28 (29%) | |

| Haken shain | 1.19 (100%) | 0.18 (16%) | 0.84 (71%) | 0.16 (13%) | |

| Keiyaku shain | 2.91 (100%) | — (—) | 2.70 (93%) | 0.19 (7%) | |

| Shokutaku shain | 1.19 (100%) | 0.18 (15%) | 0.95 (79%) | 0.06 (5%) | |

| Other | 1.19 (100%) | 0.52 (44%) | 0.41 (35%) | 0.20 (17%) | |

Notes: Prepared by the author based on the Employment Status Survey (2012) conducted by the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. As some respondents did not answer the question about contract status, figures may not add up to 100%. Company directors were not included in the survey.

The table shows that 69% of all employment is based on permanent contracts. At 92%, the vast majority of seishain have contracts with no specified end-date, but nonregular employees are not necessarily all on fixed-term contracts. In fact, 30% of hi-seishain have permanent contracts.

With permanent contracts, workers can more easily plan their future lives. In a time of labor shortages, corporations can secure talented employees over the long term. To ensure “equal pay for equal work,” the government should introduce a law whereby employees on permanent contracts doing essentially the same work are treated the same, whether or not they are described as “regular employees.”

Those on comparatively less stable fixed-term contracts include short-term workers with contracts of one year or less, who are considered statistically as “temporary or daily” employees. These people account for 15% of all workers and 38% of nonregular employees. They do not get the same opportunities for workplace training as permanent employees and those on long-term contracts. Increasing the number of permanent workers and making long-term contracts standard whenever possible would bring an increase in the number of people with stable employment.

Employees with Unclear Contract Status Worst Off

Then there are people who are unsure of their contract status. They find themselves in a yet more unstable position than temporary or daily workers.

The table indicates that 4.45 million people—8% of all workers—answered that they did not know if they were on a permanent or fixed-term contract. This includes 16% of employees in “nonregular” positions and 29% of those in jobs described as arubaito. The proportion of people whose terms were unclear was particularly high among workers in their teens and early twenties, as well as employees over the age of 60. The proportion was also high among women, employees of small businesses, and people who regularly changed their jobs.

Respondents who did not know their job status were paid less and provided with fewer training opportunities by their employers than not only permanent but also fixed-term employees. As well as expanding permanent and long-term fixed-contract employment, Japan must do its utmost to reduce the number of employees with undefined contract terms.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 23, 2016. Banner photo: University students at a company recruitment information session in Tokyo in August 2015. © Jiji.)(*1) ^ Other than “dispatch workers” for haken shain, Japanese terms for hi-seishain lack clearly defined English equivalents. The words are frequently distinguished from each other by their association with housewives earning some extra money for the home finances (pāto), students and people in other positions taking on work on the side (arubaito), and employees rehired after retirement (shokutaku shain), although there is considerable overlap in their usage. Keiyaku shain means literally “contract workers.”—Ed.