When Beatlemania Came to Japan

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

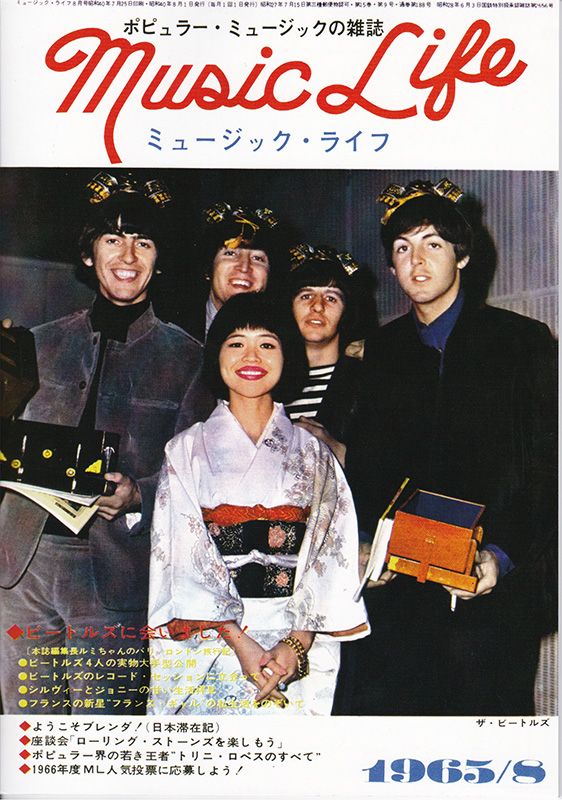

I met the Beatles in June 1965. I boarded a plane for the first time in my life and flew to London for an exclusive interview with John, Paul, George, and Ringo at EMI’s legendary Abbey Road studios. A year later, the Beatles came to perform in Japan, at the Nippon Budōkan. Following that original interview in 1965, I was able to meet and interview the Beatles every year until the band split in 1970. This wonderful opportunity gave me a precious glimpse of the personalities beyond these icons of my generation. (I was born the same year as John Lennon.) As 2016 marks 50 years since Beatlemania hit Japan, in this article, I look back on my meetings with the four men at the heart of a musical revolution and their impact on mid-1960s Japan.

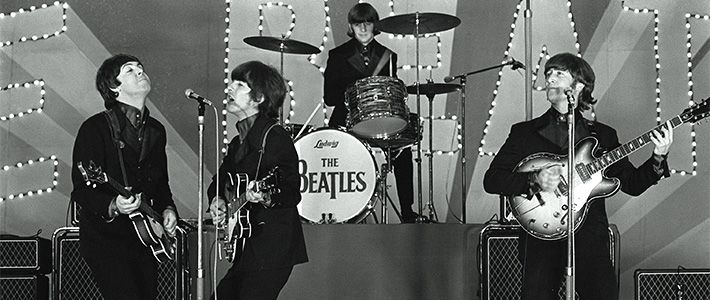

The cover of Music Life’s August 1965 issue, which contained the author’s interview with the Beatles at Abbey Road studios.

The cover of Music Life’s August 1965 issue, which contained the author’s interview with the Beatles at Abbey Road studios.

Meet the Beatles

I started hearing about the Beatles some years after I began my career as an editor at Music Life, which I had joined straight out of college. It was my love of American rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, and Elvis Presley that had led me to join a music magazine. In the beginning, I wasn’t particularly interested in a British pop group like the Beatles.

In 1963, the band’s name began to appear regularly in the American music magazines I was reading. When they toured the United States in 1964, tens of thousands of screaming fans filled the streets wherever they went. News of their sensational reception soon reached Japan. From the second half of 1964, we noticed a growing interest in the band among our readership, with girls stopping by our offices on their way home from school to ask if we had any fresh news on the Beatles or to beg us for photos of the band. Apparently they’d heard Beatles records on the American Forces Far East Network (FEN) and other late-night radio stations.

The first Beatles single to be released in Japan was “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” It was as successful in Japan as it had been everywhere else. But for me, used to American rock ’n’ roll of the 1950s, there was something strange about the Beatles sound, and at first I assumed that their music would be just a passing fad.

Despite my reservations, the band’s popularity among young people meant that we definitely wanted to cover this new phenomenon. Music Life’s first editor-in-chief, Kusano Shōichi, told me to go to London and interview the group. As if it were the easiest thing in the world! I used all my connections in Japan and other countries and tried to come up with a way to meet the Beatles. Of course I wrote to the band’s manager, Brian Epstein, begging an interview, but the reply was not encouraging: “Absolutely not.” His desk was already buried under a mountain of similar requests from journalists around the world.

In the end, I flew to England in June 1965, on the advice of a contact who worked for EMI in London. My contact told me that the Beatles were in London till the end of June recording what became the Help! album, and that this represented my best chance to meet them. And then, just one week before I was due to depart, Mr. Kusano stepped down and I took over as editor-in-chief.

I had an appointment with Brian Epstein, but of course no promise of a meeting with the Beatles themselves. It would be unthinkable today, but I took with me a Japanese samurai sword as a present. Thinking that one sword on its own might draw unwanted attention, I bought four fake swords to go along with the genuine one and wrapped them in paper as part of my carry-on baggage. I visited Hamburg and Paris for interviews before proceeding to London, and not once as I passed through customs did anyone give my collection of swords a second look.

Three Hours in Abbey Road

Even if he didn’t know much about Japan, Epstein would have been well aware that the Japanese music market was booming dramatically at the time. Probably, though, his policy was that he didn’t want to give special treatment to any one journalist when he was swamped by requests from the world’s media. Eventually, perhaps impressed by the determination that had brought me all the way from the Far East, or perhaps pleased by the samurai sword I had brought with me as a gift (he told me he knew Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai), he eventually agreed to let me meet the band.

With John Lennon and Paul McCartney during my interview with the Beatles at Abbey Road on June 15, 1965.

With John Lennon and Paul McCartney during my interview with the Beatles at Abbey Road on June 15, 1965.

The Beatles and their producer George Martin (wearing a necktie, at back ) look through copies of Music Life.

The Beatles and their producer George Martin (wearing a necktie, at back ) look through copies of Music Life.

It was just after five in the afternoon of June 15 that I set out for the EMI studios in Abbey Road, where the Beatles were recording. Producer George Martin welcomed me to the mixing room of Studio 2. The Beatles were downstairs in the studio. Curious about this new arrival, dressed in a kimono, they stopped their conversation and looked up toward me in the mixing room. Paul McCartney pointed to the staircase and gestured at me to come down into the studio.

They’d been told that a journalist was coming to interview them, but probably hadn’t expected someone like me: a small (150-centimeter) woman dressed in a kimono. George Harrison rushed over and started asking me questions. Why was I wearing such a huge belt? And why were my sleeves so long? My decision to wear a kimono turned out to have been an inspired decision, proving an ideal icebreaker and talking point.

I think the sight of me—around the same age as they were, speaking hesitant English, small, and obviously harmless—put them at ease. They opened up right away. I’d been told I had only thirty minutes for my interview, but in the end I was with them for three hours. We’d solicited questions for the four Beatles from Music Life readers. When I handed a piece of paper with around ten questions to Paul, he took one look at it and said, “With your English, this’ll take all night,” and hurriedly passed question sheets to his bandmates. They all started dutifully writing their answers to our readers’ questions.

The most talkative of the four was John. At first he’d struck me as a bit reserved, but he soon relaxed and started cracking jokes. He seemed to know a fair bit about Japan, and told me he wanted to meet a sumō wrestler if he visited the country. He said a friend at art college had shown him a collection of old photos of Japan, including some “beautiful” photos of sumō wrestlers. “I can speak Japanese, you know,” he told me, before launching into a demonstration of pseudo-Japanese babble.

From London I flew to the United States for a month of interviews and other work. When I got back to Japan the issue with my Beatles interview was already in the shops. We normally sold around 50,000 to 70,000 copies per issue, but for this issue we printed 250,000 copies, almost all of which were snapped up.

Beatlemania Comes to Japan

It was not long after New Year in 1966 when the first rumors began to circulate that the Beatles were coming to Japan. I remember meeting the promoter Nagashima Tatsuji of Kyōdō Kikaku (now Kyōdō Tokyo), who asked me for my personal impressions of the Beatles as people. I told him that the Beatles had been charming but that their manager Brian Epstein was a tough customer. It was a little after that that the group’s tour was confirmed.

There were several major sponsors for the Beatles performances in Japan: Kyōdō Kikaku, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, and the Chūbu-Nippon Broadcasting Company. The tour was to involve five performances between June 30 and July 2, and applications for tickets had to be made by sending a postcard to the Yomiuri Shimbun, by entering prize competitions run by sponsors including Lion toothpaste and Toshiba Musical Industries (the distributors of the Beatles’ records in Japan) or by entering a ticket lottery by buying a round-trip air ticket on JAL. Many young women tried a combination of all these methods in a desperate attempt to get their hands on tickets.

While young people were generally enthusiastic about the Beatles, many older people objected to their style of music and long hair. Conservative adult audiences at the time preferred presentable, clean-cut groups like the Brothers Four, an American band who combed their hair into neat partings and sang unthreatening “college folk” music.

The Beatles arrived in Japan early on the morning of June 29, delayed by a typhoon. They held a press conference later that afternoon. The four Beatles sat in a row on stage and it was announced that three officially approved journalists would be allowed to ask questions as representatives of the press. The journalists solemnly read their questions from old-fashioned scrolls of paper. I couldn’t help laughing at the absurdity of the scene from my seat in the press section. The Beatles must have been surprised by the stiff formality of the press conference, but nevertheless provided witty and evasive answers to the questions.

John Lennon’s Strange Outburst

I met the Beatles for the first time since their arrival in Japan on the afternoon of July 2. I was the only journalist to receive an official invitation to visit them in their presidential suite on the tenth floor of the Tokyo Hilton. There was a constant stream of people coming and going, and the atmosphere wasn’t at all conducive to a conventional interview. The band members hadn’t been given permission to leave the hotel, and were whiling away their time sketching doodles for fans and listening to the records of Japanese folk songs they had received from the tour’s sponsors. When I entered the room they were looking at cameras and other souvenirs that had been brought in for their perusal, including various kimono and obi. They seemed particularly interested in cameras, and I remember them asking Hasebe Hiroshi, my photographer, for advice on which were the best to buy.

At the Tokyo Hilton, July 2, 1966, introducing John and Ringo to the signature pose made famous by a character in the Osomatsu-kun, a manga and anime popular in Japan at the time. John had asked me about what kids in Japan were into. Ringo apparently struck up the pose himself later on, but sadly the moment was not captured for posterity.

At the Tokyo Hilton, July 2, 1966, introducing John and Ringo to the signature pose made famous by a character in the Osomatsu-kun, a manga and anime popular in Japan at the time. John had asked me about what kids in Japan were into. Ringo apparently struck up the pose himself later on, but sadly the moment was not captured for posterity.

John kept coming and going in and out of the room. Suddenly he picked up a glass of orange juice that had been sitting on top of a table, raised it high and shouted out something. I wasn’t sure, but it sounded to me like “The Beatles will fade out.” Everyone treated this as a joke and laughed it off, but Ringo who was next to me pointed over at Epstein and said “Brian. We’ve made all this money, but where can we spend it? We’re not allowed out of the hotel.” Later, Epstein came over to me and put his finger to his lips. “You mustn’t write anything about what John just said,” he told me. He was serious.

I went to see the Beatles in concert twice: on the opening night and on July 2, the final night of their tour. There was loud screaming throughout the performances, but it was not so loud that I couldn’t hear what they were singing. And I remember the girls shushing one another when it came time for Paul to perform “Yesterday.” The whole hall suddenly seemed to fall silent.

Watching Lennon and McCartney at Work

The visit to Japan totally changed the way people in this country viewed the band and their music. Before the tour, there were protests against the idea of allowing the “sacred space” of the Budōkan, which had been built as a venue for Japanese martial arts, to be sullied by a group of long-haired rockers from Liverpool. Right-wing extremists trawled the streets in their black vans calling for a ban to keep the Beatles out of Japan.

The Beatles were only in the country for a little under five days, but that short visit was enough to change public opinion totally. People soon realized that they had no choice but to embrace the Beatles. Sales of the band’s records went through the roof after the visit and the media, which had previously been somewhat non-committal, suddenly adopted an effusive, adoring tone. Many adults who hadn’t previously been interested in the Beatles took the opportunity to listen to their music for the first time, and realized that the songs weren’t bad after all. Following the Beatles path-breaking tour, it became routine for major bands to perform at the Budōkan. The social pressure on young people relaxed in various ways after the visit.

Fifty years after their performances at Budōkan, Japan’s passion for the Beatles shows no signs of fading. Here Hoshika gives another talk about her meetings with the band.

Fifty years after their performances at Budōkan, Japan’s passion for the Beatles shows no signs of fading. Here Hoshika gives another talk about her meetings with the band.

After the shows in Japan I received an offer to cover the band’s performances in North America in August 1966 for what became their final tour, and from then on met the Beatles every year until the band split in 1970. I was lucky enough to be on hand for several precious moments in Beatles history. Between rehearsals before the band’s opening concert in Chicago in 1966, I remember John Lennon suddenly appearing stark naked in front of me out of the shower and shouting, “Hey Rumi, toss me a towel from that chair will you?” Apparently it was a joke.

In September 1967 I was in London again at a recording session as John and Paul worked together to finish up the lyrics to “The Fool on the Hill.” I was not the only Japanese woman in the studio that day. Also sitting in a corner of the studio was Ono Yōko, whose relationship with John Lennon would make headlines around the world by the end of the year.

I also happened to be present at the now legendary rooftop concert in January 1969. I had gone to London for another job, when an employee of Apple Records—founded by the Beatles—contacted me, telling me they would perform on the roof and inviting me to go and see them. I thought it was just a one-off with the four members getting together on a whim for the first time in a long time, so I was surprised later on when the album and film versions of Let It Be were released.

Precious Memories

When the news broke that the Beatles had split up in 1970 I was disappointed but not really surprised. Apple had been struggling since 1968 and the four Beatles had hardly been seen at the company apart from the day of the rooftop performance. Although I’d been privileged to watch John and Paul collaborating happily on the lyrics for “The Fool on the Hill,” even a cursory listen to their next album The Beatles (commonly known as The White Album), released in 1968, was enough to make it clear that the two driving spirits of the band were heading in quite different directions. I felt it was only a matter of time until they decided to go their own separate ways.

At the time, I could never have imagined that we’d still be talking about the Beatles fifty years later. Their songs, of course, have a universal appeal that reaches out to people across distance and time. But I think Japan is the only country in the world where special events are held to mark every significant anniversary of their visit. Perhaps even more than in other countries, I think many fans in Japan still treasure their precious memories of the Beatles and their visit to our shores all those years ago.

(Written by the Nippon.com editorial department based on an interview conducted in Japanese on June 25, 2016. Banner photo: The Beatles perform at the Nippon Budōkan on June 30, 1966 .©Jiji Other photographs courtesy of Shinko Music Entertainment.)