Ninoshima: Island of Refuge

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Mystery writer Naomi Hirahara’s father Isamu was born in California, but was taken as an infant to Hiroshima, where he survived the atomic bombing in 1945, just miles from the blast. Her mother Mayumi, born in Hiroshima, lost her father to the bomb. Shortly after the end of World War II, Isamu returned to California and eventually established himself in the gardening and landscaping trade in the Los Angeles area. After Isamu married Mayumi in Hiroshima in 1960, the couple made their new home in Altadena and then South Pasadena.

In August 2016, with an Aurora Challenge Grant from the Aurora Foundation in Los Angeles, the author made a trip to Japan to learn more about the history of the small island of Ninoshima near Hiroshima and its connection with the atomic bombing. Below she writes about the research she did there in preparation for the seventh and final installment of her Mas Arai mystery series.

Visiting a Hiroshima Island

I am obviously one of the few newcomers to Ninoshima on this 20-minute ferry ride from the port of Ujina, in the south of the city of Hiroshima. For one thing, I am standing and studying the color map of the island affixed to one of the boat’s walls. The other passengers—many of them elementary school children—sit in the galley, more interested in each other than in the looming green mound of Ninoshima in the distance.

At 278 meters in height, Aki no Kofuji, the island’s top peak, is called Hiroshima’s Mount Fuji. This peak attracts hikers to the island; then there are bicyclists that dare to tackle the narrow, windy street that circles Ninoshima. Oyster harvesters have established a base on the island, with poles of scallop shells anchoring oyster spat visible at low tide. And the island has its own elementary and junior high schools, situated right next to one another.

But I’m not going to Ninoshima for the hiking, fishing, water sports, oysters, or school. I’m going to learn about how the island has historically been a refuge for the Japanese at times of transition and great trouble. Now only supporting a population of less than 1,000, no one—not the Japanese and not even Hiroshima’s urban residents—knows much about Ninoshima. But I have some direct ties to the island: One of my mother’s relatives helped establish a senior citizens’ home there, and others continue to operate it. As a result of this connection, I’m able to take a peek into a place that perhaps outside people may have forgotten but history has definitely not.

Poles of scallop shells anchoring oyster spat are visible at low tide.

Poles of scallop shells anchoring oyster spat are visible at low tide.

A Place of Refuge

The island once served as a former quarantine medical center housing soldiers returning from the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), when there was concern about the ongoing global cholera epidemic. It later became an internment center for German prisoners during World War I, explained Miyazaki Kazuo, a former town representative who is a self-described “peace volunteer guide.” After the bomb fell, when the injured and sick needed a place to go, that place happened to be Ninoshima.

As Ninoshima still had its large structures intact, atomic bomb casualties were transported there in lifeboats. It’s amazing to imagine this tiny island being a refuge for 10,000 victims. In fact, many of the searing photos of men and women burned by the blast were taken on the island.

The victims stayed here for 20 days. Of course, many died, but the ones who survived were eventually transferred to other, better-equipped medical facilities in Japan.

The story of Ninoshima and its connections to war could have ended there. But there was a greater force—a redemptive spirit—that would not release the island. In the following year, 1946, a home for children who had been orphaned due to World War II, Ninoshima Gakuen, was built.

Thirty-four children, their clothing tattered and heads shaven, were part of the inaugural group who made Ninoshima Gakuen their home. Later in 1967, this facility was joined on the island by the retirement home Heiwa Yōrōkan, established by a nonprofit that had one of my relatives, Mukai Satoshi, as its founding director. The facility later expanded its services to include assisted care. Most retirement homes up to this time were under the umbrella of a Buddhist temple, so to have one independent of that affiliation was groundbreaking.

The Kannon statue in front of the Heiwa Yōrōkan erected to pray for the victims of the atomic bomb.

The Kannon statue in front of the Heiwa Yōrōkan erected to pray for the victims of the atomic bomb.

Just to the south of the island’s elementary and junior high schools is a memorial cenotaph commemorating the atomic-bomb blast—nothing special compared to Hiroshima, in which similar plaques are placed throughout the city. However, this one marks the approximate location in which a mass grave of 617 bodies was discovered on the grounds of the junior high school in 1971. The bones were transferred across the bay to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The discoveries continued in 2004, when the remains of 85 people were uncovered in a field across from the school.

Blooms of Hope

The official Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony is on August 6, but Ninoshima has its own two days earlier, on August 4. I am told that it is much smaller, a village version, but I actually look forward to this more intimate gathering.

I spend the night at my relatives’ retirement home and wake up early on August 4.

The sun is out and you can feel the hot humidity rising from the ground. I take a walk and snap photographs. I’ve spied an earthworm the length of my shoe and two men playing gateball, a game like croquet popular with older Japanese, in a field near the island’s tennis courts. I eventually head for the coast. On an empty country road the croaking of the cicada is broken up by the putt-putt of a scooter.

An older woman, wrapped in clothing and wearing a hat to shield herself from the punishing sun, parks her scooter next to a garden across from the white tent set up for the memorial service. She heads for a gardening shed and I wander onto the garden, which abuts a slope.

There’s a sign there marking the field as Irei no hiroba, or a place to comfort the dead. The sign explains that the various plots of flowers represent the six rivers of Hiroshima.

The sign explaining the commemorative area where the remains of many A-bomb victims were discovered.

The sign explaining the commemorative area where the remains of many A-bomb victims were discovered.

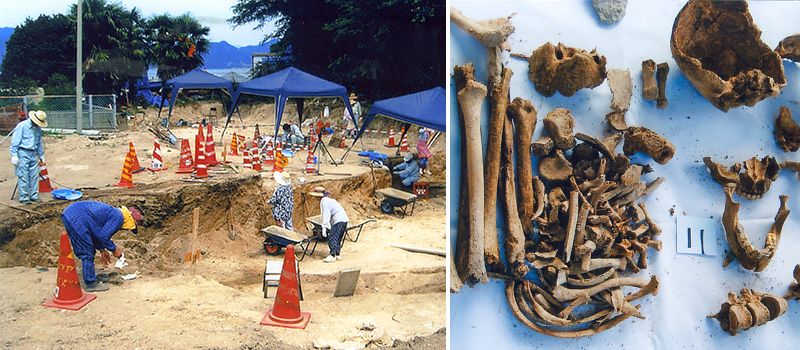

A digging of the remains in 2004 (left) and the excavated bones. (Photos courtesy of Miyazaki Kazuo). The remains are now collectively enshrined at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

A digging of the remains in 2004 (left) and the excavated bones. (Photos courtesy of Miyazaki Kazuo). The remains are now collectively enshrined at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

As I’m gazing at the stalks of a sunflower varietal, the woman on the scooter says to me in Japanese, “These were my idea.” Holding a garden hose, she explains that she’s not from the island, but moved there with her husband a couple of decades ago. Amidst the sadness, loss, and horror of war, she wanted to plant flowers.

She beckons me to enter the shed. Next to the gardening edgers are black and white photographs pasted on the wooden walls. As I write mystery novels and was introduced to the legacy of Hiroshima as a 14-year-old, the images don’t immediately shock, but they do seem out of place in this idyllic spot. Images of dark skulls stacked together, human bones measured and identified. It’s almost too much to process on this increasingly hot day.

Slowly people in black clothing begin to fill the folding chairs underneath the white tent. The only thing really adding color to the ceremonies is a row of brilliant yellow and gold decorations, which I later learn are a typical offering in Hiroshima during the Obon season.

Traditional Obon decorations in Hiroshima.

Traditional Obon decorations in Hiroshima.

Local schoolchildren attend the memorial ceremony.

Local schoolchildren attend the memorial ceremony.

I take a seat underneath the tent, again probably one of the few newcomers and probably the only foreigner there. Children from the neighboring elementary school, on summer break yet dressed in uniforms for the ceremony, fill the back rows. Buddhist priests chant and one of them speaks, mentioning his own grandmother, a hibakusha (atomic-bomb survivor), as well as US President Barack Obama’s visit to the Hiroshima Peace Park earlier that year. Incense is offered and the ceremony ends within 45 minutes.

The Inochi no tō (Monument of Life) located on the hill above Ninoshima Gakuen.

The Inochi no tō (Monument of Life) located on the hill above Ninoshima Gakuen.

It’s there where I meet Miyazaki, who tells me the history of the island. We later go to Ninoshima Gakuen, which is no longer a traditional orphanage but more of a place for children who cannot live at home with their parents. From an administrator, I learn how counselors work with the children to get them to voice their emotions and feelings—something not often encouraged in Japan, at least in educational settings.

Miyazaki takes me up to where a statue stands on the hill above the Gakuen. From a distance, it resembles a child floating in the middle of the green foliage, but now I see that it is Buddhist, inscribed with the writing Inochi no tō (Monument of Life). The statue was erected in 1971 to commemorate the children’s home’s twenty-fifth anniversary. There’s a small vault in the back holding the ashes of those who worked there and some who stayed there.

Since my smaller ferry to take me back to Hiroshima City is due to arrive at Gakuen Pier, we make our way down the hill. As we walk through a crowd of children approaching the dirt playground, I hope that Ninoshima is their transitional place, their place for a second chance. While bones of the past are still being discovered, I hope that the island is not haunted by destruction, but is rather a haven for life—good soil for wildflowers as well as the blooms of hope sown by its residents.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Aki no Kofuji seen from the Hiroshima Port side of the island. Courtesy of Miyazaki Kazuo.)