Japanese Society Needs a Truly Global Approach

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Securing global talent capable of competing in global markets is a major challenge for Japanese industry. Business managers commonly complain that Japanese young people are inward-looking “herbivores” who are no longer interested in venturing out into the world beyond Japan. They claim that this puts Japan in a dangerous position at a time when global talent is in high demand, and call for more young people to study abroad.

But are young people in Japan really so insular? In fact, compared to the current crop of business leaders, Japanese youth are far more global in outlook and have much more global experience. What’s holding them back are the global management policies of the Japanese business world.

Studying Abroad Is Actually on the Rise

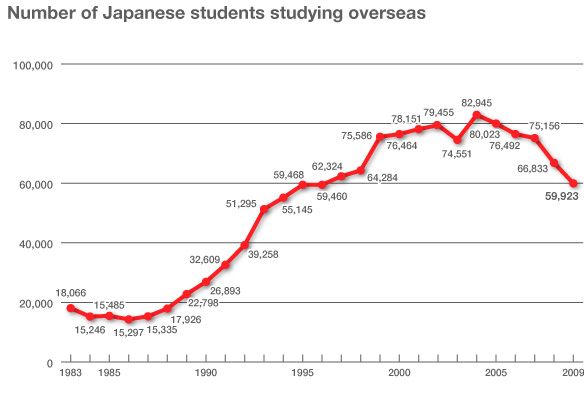

Statistics from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and other sources reveal that the number of Japanese students studying overseas peaked at 82,945 in 2004 and declined thereafter, falling to 59,923 in 2009. Japan has been surpassed in this respect by both China, which has over 500,000 students studying abroad, and South Korea, with over 100,000. Based on these numbers alone, it could be said that young people in Japan are more “inward looking” than those in other countries.

Number of students studying abroad in 2009

| Country or region | Number of students (previous year) | Year-on-year increase/decrease | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 24,842 (29,264) | –4,422 | –15.1% |

| 2 | China | 15,409 (16,733) | –1,324 | –7.9% |

| 3 | Britain | 3,781 (4,465) | –594 | –13.3% |

| 4 | Australia | 2,701 (2,974) | –273 | –9.2% |

| 5 | Taiwan | 2,142 (2,182) | –40 | –1.8% |

| 6 | Germany | 2,140 (2,234) | –94 | –4.2% |

| 7 | Canada | 2,005 (2,169) | –164 | –7.6% |

| 8 | France | 1,847 (1,908) | –61 | –3.2% |

| 9 | New Zealand | 1,025 (1,051) | –26 | –2.5% |

| 10 | South Korea | 989 (1,062) | –73 | –6.9% |

| Other | 2,952 (2,791) | 161 | 5.8% | |

| Total | 59,923 (66,833) | –6,910 | –10.3% | |

Sources: OECD, Education at a Glance; UNESCO Institute for Statistics; Institute of International Education, Open Doors; Ministry of Education, People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan).

- Definitions of a student studying abroad:

- OECD, Education at a Glance

A person enrolled and pursuing a formal course of study at an institution of higher learning who is not a permanent resident or citizen of the host country. - UNESCO Institute for Statistics

A student enrolled at an institution of higher learning who is not a permanent resident or citizen of the host country. - Institute of International Education, Open Doors

A person enrolled at an institution of higher learning in the United States who is not a US citizen or permanent resident. - Ministry of Education of The People’s Republic of China

A person who holds a student visa (an X Visa valid for a period of study of at least 180 days) or a visitor’s visa (valid for less than 180 days) and is enrolled at a university in China. - Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan)

A person enrolled at an institution of higher learning in Taiwan (including students engaged in short-term overseas study).

What that conclusion overlooks, though, is the fact that the population of young people in Japan is declining. If we compare, for example, the percentage of eighteen year-olds in Japan who have studied abroad, a different trend emerges: 1.0% in 1985, 3.4% in 1995, 5.1% in 2000, 5.9% in 2004, and 5.0% in 2009. In other words, the proportion of young people studying overseas has quintupled since the 1980s. The actual numbers, meanwhile, have doubled. If we look back to the era when today’s sixty-something business leaders—now bemoaning the lack of global talent—were themselves young, we see that even fewer Japanese were studying abroad. The young people of today may be more inward-looking than their counterparts in other Asian nations, but compared to previous generations in Japan they are not inward-looking at all.

The soaring value of Japan’s currency, which now exceeds 80 yen to the dollar, might be expected to boost to overseas study, but in reality this does not seem to happening. Why not?

As I see it, young people are behaving quite rationally in light of the current state of the Japanese business world, or, to put it more strongly, the state of Japanese society. If you propose to spend ¥4 million a year, including living expenses, studying overseas, then what return on that investment can you expect? The Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) and others in the business world are advocating greater diversity in hiring practices, but the mass hiring system predicated on the enrollment of new recruits each April will continue to be the norm for some time to come. Given that factor, and today’s bleak employment outlook, young people seeking corporate jobs find it more advantageous to attend university in Japan than to study overseas.

It can cost as much as ¥10 million to study overseas for two years at a business school in the United States. The prospective overseas student has to consider whether he or she can recover such an investment. If she earns an MBA degree and goes to work for an international corporation overseas, she can expect a high annual income, but not if she intends to go back home and join a Japanese company. Faced with the criteria for employment in the Japanese business world, young people in Japan have concluded that it makes economic sense to forego overseas study.

Globalization Is Testing Japan’s Business World

The older generation, appealing to idealism, has been urging young people to be less calculating and more open to taking risks, but this has not improved the situation. There are only two strategies available.

First, Japanese management needs to go global. The mass hiring of university graduates should be done away with immediately, and the disparate treatment of Japanese university graduates and graduates from universities overseas should end. Japanese jobseekers and those of other nationalities should naturally receive equal treatment when it comes to hiring. Those who have acquired an MBA degree at their own expense should be well compensated. Unless the Japanese business world and society as a whole are willing to hire people who have studied abroad (whether citizens of Japan or some other country), there will be little incentive for young people to go overseas.

The other key strategy is for Japanese universities to go global, too. This will require enabling students to acquire the same level of linguistic ability and specialized knowledge whether they attend university in Japan or overseas. It would also require improvements to make it easier for outstanding students from other countries to study in Japan. More venues like Akita International University are needed, where Japanese students and students from other countries can display their abilities in an atmosphere of friendly competition. Instead of a situation in which the path to global talent is only open to those who can afford to study abroad, we can enhance both the quality and quantity of the global talent pool by providing such options within Japan’s own borders.

Complaining about “inward-looking” young people is pointless. The challenge now is whether the Japanese business world, Japanese universities, and Japanese society as a whole can muster the will to break free of their own insular ways.

(Originally written in Japanese on June 21, 2012.)globalization student study abroad university Yasui Takayuki Asahi inward-looking overseas study Keidanren Japan Business Federation MBA Akita International University global talent