Education in Japan: The View from the Classroom

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

One of the dominant trends in Japanese education policy in recent decades has been the idea of yutori kyōiku, or “education that gives children room to grow.” The policy was based on the idea of reducing the burden placed on children by their studies, allowing greater flexibility and helping to encourage more independent thinking. The system created more space for extracurricular activities and community service, and introduced “time for integrated studies.” Classroom hours were reduced and a five-day school week was introduced across the board, doing away with Saturday classes. Since these reforms, however, there has been an alarming drop in the performance of Japanese schoolchildren in surveys such as the Program for International Student Assessment. The new curriculum guidelines, which will come into full effect when the new academic year starts in April 2012, have been widely seen as marking the end of the yutori kyōiku experiment. The new guidelines will increase the number of classroom hours in all subjects by roughly ten percent throughout the three years of junior high and six years of elementary school, and place a renewed emphasis on critical thinking, discernment, self-expression, and the acquisition of basic knowledge and skills.

Nothing Wrong With the Idea of “Room to Grow” Education

I don’t think there was much wrong with the basic idea behind yutori kyōiku, which was to encourage children to think for themselves. If there was a problem with the system, it was that the ideas did not permeate sufficiently to teachers and guardians, and that concrete measures for putting the ideas into practice did not function properly in the classroom.

For much of the postwar period, the priority for education in Japan has been on rote memorization of facts. In Japanese, this approach is known as tsumekomi, or “cramming.” The widely shared feeling that this approach had failed to inspire initiative and an appetite for study was what led to a change of direction, in favor of a more relaxed and flexible style of education. Classroom hours were reduced and schools introduced “integrated study” time in which creative, varied learning could take place. Elective classes were introduced to encourage students to be more independent and proactive, and to allow more progressive learning.

But in fact, running the new, flexible “integrated learning” classes turned out to require more energy than most people had imagined. The content of the new classes also depended to a significant extent on the characters and abilities of individual teachers. This meant that there were substantial differences between what different schools were doing. In quite a few cases, the classes were used as convenient chunks of time in which to prepare for sports days, class trips, or other school events. There were problems with elective classes too, such as limitations in the kinds of buildings and facilities available. Children were not always able to choose the options they wanted, and in many cases staff members did not have the extra resources to organize a progressive curriculum. There was thus a substantial gulf between the ideals of yutori kyōiku and the reality in the classroom. There is no doubt that many teachers and schools felt they had had a system thrust upon them that poorly suited their requirements and capacity to cope.

Another major problem was that yutori kyōiku went too far in reducing classroom hours. A certain level of classroom time is essential to ensure that children learn the basics. Ironically, the radical reductions to classroom time meant that more remedial classes were necessary, placing an even heavier burden on teachers. This failure to teach the basics properly also seems to account for why the yutori kyōiku approach fell short of its chief objective of nurturing children’s ability to think for themselves.

There is no doubt that the postwar school education was a vital part of Japan’s rapid economic growth. The fact-based, cramming method worked well in the years when Japan’s economy was going from strength to strength. But inevitably, growth reached a plateau as the economy matured. In a rapidly changing society where diverse values coexist, self-motivation and initiative are absolutely vital. In this respect, the decision to overhaul the education system was commendable. To repeat: There was little wrong with the ideals themselves.

The new educational guidelines that are already in effect in the country’s elementary schools (and will be introduced to junior high schools from the start of the new academic year in April 2012) maintain the ideals of yutori kyōiku while incorporating concrete measures to solve problems that arose from them. I think this represents real progress. The new guidelines demonstrate an awareness of the importance of ensuring both the necessary number of class hours to provide children with basic knowledge and skills in all subjects, and of nurturing the skills of critical thinking, discernment, and self-expression to allow them to make use of this knowledge; a healthy balance between those two sides is maintained.

Another yutori kyōiku idea that merits sympathy is that students’ language skills should be improved by comprehensive activities spread right across the curriculum, rather than solely through Japanese classes. The shift from the traditional extended family to the nuclear family, the weakening of community ties, and the spread of mobile phones and email and messaging services, are all depriving children of opportunities to hone their linguistic skills. Designing an improved language curriculum that uses a variety of activities to restore these skills is one important way for schools to contribute positively to children’s future.

The new curriculum will probably ensure that scholastic standards improve at least to some extent, but if the guidelines are to succeed in their broader aim of giving children “strength for life,” it will be necessary not only for teachers but for parents, guardians, and all the others involved in our children’s education to understand the underlying ideals and put them successfully into practice in the classroom.

Fostering Independent Young People Who Can Contribute to Society

In what follows, I would like to introduce a few of the concrete measures we have introduced at Wada Junior High.

In 2003, Wada Junior High School became the first in Tokyo to recruit a principal from the private sector. Since that time, the school has implemented a number of ambitious and far-reaching reforms. In 2008, I became the school’s second private-sector principal. Four years have passed since then, and this year marks a decade since the school began its wide-ranging reform program. There are many differences between me and my predecessor, Fujiwara Kazuhiro: our ages, our backgrounds, and our management methods are all quite different. But one thing we have in common is a strong desire to use our experiences in business to educate children to be self-reliant in society.

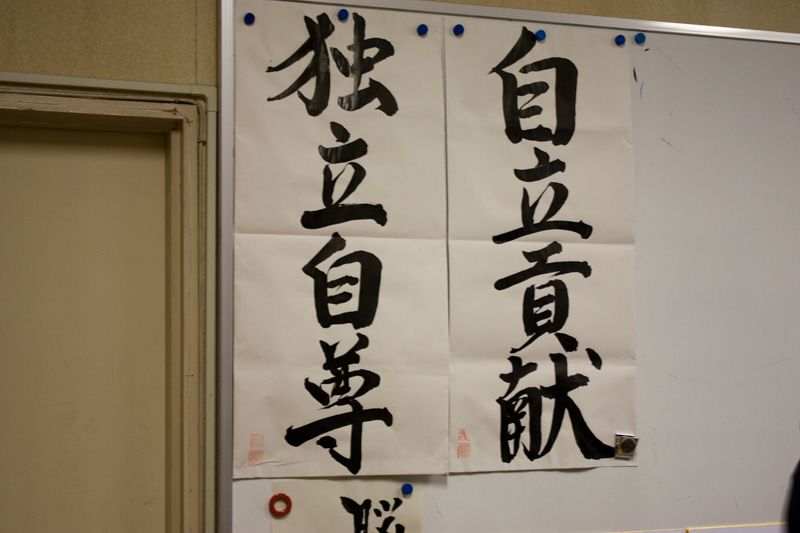

The school motto hangs in the principal’s office

The school motto hangs in the principal’s office

The aim of school management at Wada Junior High School—what you might call our educational vision—is encapsulated in the school motto: “Autonomy and Contribution: Dedicate Yourself to Achieving Your Dreams and Contributing to Society.” Given the hard times we are living through, having hopes and dreams is not easy for many children. But although they may taste defeat or disappointment, we want them to hold on to their dreams and hopes and become the optimistic standard-bearers for a new society, thinking and acting for themselves. This aim lies at the heart of all our efforts. Of course our students need to work hard to pass their high school entrance exams. But as these 13-year-olds stand on the threshold of adulthood, it is more important that they start to think seriously about the lives they will lead after they leave school and go out into the wider world, and to consider the needs of society rather than their own self-interest. We believe that it is necessary to teach children to be considerate of others and to develop an awareness, not of self-sacrifice exactly, but of the importance of making a contribution to others.

At Wada Junior High School, we have always had a clear vision of the kind of students we are aiming to produce. I think this is one reason why we have been successful in implementing so many reforms. We have worked hard to make the school’s educational vision—encapsulated in the motto, “autonomy and contribution”—familiar not only to students and teachers, but also to parents and guardians and others in the local community. This is a crucial part of winning people’s understanding and support for our aims and ensuring that everyone is moving in the same direction. I think this has been a major factor in allowing us to carry through our reform program.

Learning about the World Through Lessons Without Answers

One of the educational activities that embody these ideals of autonomy and contribution is a class called “The World at Large.” This is a class in which there are no right or wrong answers. In contemporary society, many problems do not have simple solutions. When today’s children grow up, they will have to confront these problems and come up with solutions of their own. That is why we believe it is so important for them to develop the habit of thinking about such problems with their teachers and peers during their junior high school years.

Renhō Murata lectures to students at Wada Junior High School

Renhō Murata lectures to students at Wada Junior High School

Do junior high school students need cell phones? Should Tokyo bid to host the Olympics? Is it appropriate to inform junior high school students about cancer? What if a military base moved to Wada? Is human cloning acceptable? — These are just a few of the questions discussed recently in the class. A wide range of guest lecturers also visited our school to help students explore these issues in depth, including doctors, lawyers, professional athletes, politicians, tatami craftsmen, and city hall officials. For example, in 2010, Renhō Murata, the minister for government revitalization, was a guest instructor for an exploration of the subject: “A Fiscal Screening Committee for Wada: Is the Child Benefit Necessary?”

Some students spoke from their own experiences: “In our family, the allowance is not used for education expenses—and in a lot of families, the money ends up being used for everyday living expenses,” one said. Another argued: “It makes no sense to collect money and merely redistribute it again as money. Instead the government should provide additional value that only the government can provide.” It made me proud to see our students speaking up and giving their opinions boldly in front of a current government minister. Such classes not only allow students to deepen their understanding of the subject matter at hand, but also underscore the basic truth that a diversity of opinion exists in society, and enable students to think about the issues more deeply.

But two or three classes with outside instructors a year are hardly enough to change a child’s awareness. On their own, these classes would be of little significance. But they are just one part of what we do. I lead discussions myself in a series of classes under the title “The World at Large: Next.” This involves one 45-minute period a month for first- and second-year students, for a total of ten meetings a year; and one period every two weeks, for a total of 90 minutes a month, or roughly 20 times a year, for third-year students. The “World at Large: News” class, in which students are required to write a short essay based on a news article, also takes place once a month, along with a course for each grade titled “The World at Large: Future,” which invites craftsmen and professionals to speak as guest instructors. The idea is that by the time they graduate, students will come into contact with at least 50 people who are leaders in their fields. Continuity is essential.

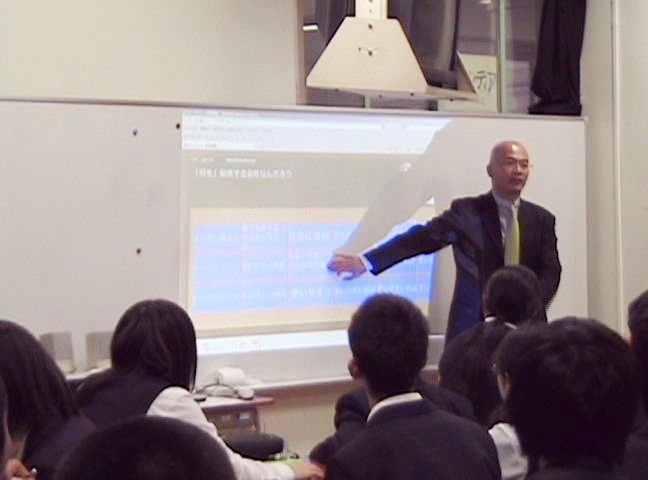

Principal Shirota leads the discussion in one of the school’s iPad lessons.

Principal Shirota leads the discussion in one of the school’s iPad lessons.

Since 2010 we have been using iPads in our World at Large classes. We developed an application that allows students to share their opinions with the whole group in real time, allowing for a lively exchange of views during class time. I believe students can learn from that diversity of opinion.

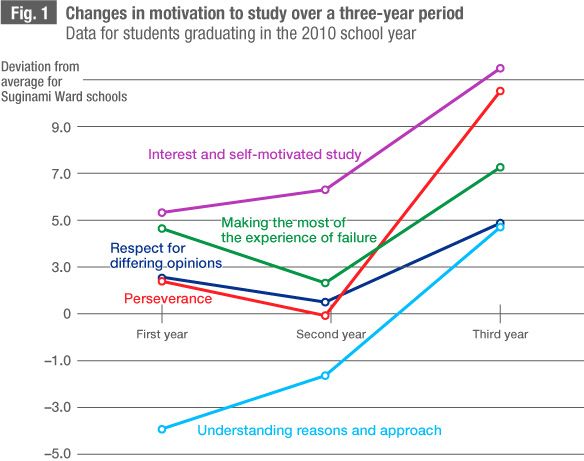

As a result of these efforts, student feedback has shown a clear increase in such areas as “understanding the reasons and approach behind something,” “interest and self-motivated study,” and “respect for differing opinions.” (Fig. 1)

Developing Diverse Communication Skills

Forging even closer connections between the school, families, and the community will continue to be a priority.

Eight years ago, the school launched the “Local Community Headquarters” to help get the wider community more involved in supporting school activities. We believe that a strong community helps to create a strong school, and that the work we do to create a good school will in turn strengthen the community. With community ties growing weaker across society in recent years, the school has made a concerted effort to organize activities that allow local community members to support the school, and that incorporate the community’s rich resources into the way the school is run.

We kicked off this effort by bringing in local people to work in the school, whether to staff the library or care for the school’s playing fields. The scope of these activities has gradually expanded. Today, activities include the “Saturday Terakoya” study support program, run mostly by local university students who intend to pursue teaching careers, and an English program that prepares students to take the standardized tests in practical English proficiency. The Local Community Headquarters is also responsible for the evening classes run in collaboration with private-sector companies. These “Night-time Specials” classes, as they are called, have been prominently covered in the media. At present, around 200 students come to school on Saturdays to take part in a variety of classes run by the Local Community Headquarters.

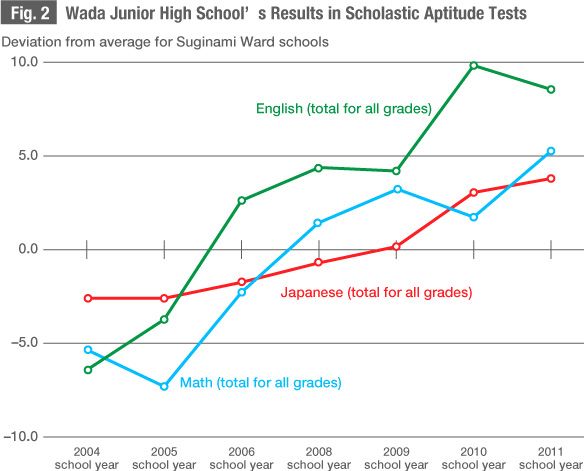

Thanks to these innovations, over the past seven years Wada Junior School has risen from a position close to the bottom of the 23 junior high schools in Tokyo’s Suginami Ward to become one of the top-ranked today in terms of academic results, placing us among the most successful schools in Tokyo.

I prefer to take the results of educational achievement assessments with a pinch of salt. It is always difficult to ascertain the precise reasons for an improvement in academic performance. I am sure our innovations have had an effect. But really our success comes down to a combination of factors: a well-balanced curriculum; a strong school ethos, with an emphasis on politeness and discipline, close liaisons with families to ensure a healthy, ordered lifestyle conducive to study; and diversity in education through our links to the local community.

What the Earthquake Revealed About Japanese Education

In the aftermath of the March 11 disaster last year, the Japanese people’s community spirit and sense of service were widely praised by the media around the world. In that sense, it is fair to say that the Japanese education system has produced some positive results.

But what about the confusion of the nation’s leaders, including certain elements of our corporate management? And the problem was not limited to just a small portion of Japan’s managers. Ultimately, I think, it stems from a failure of the education system to teach more people to think seriously about the direction and state of society as questions that concern them personally.

The yutori kyōiku policy failed to function properly because of a gulf between the ideals of the national government and the reality of life in the classroom. It is essential that similar divisions do not occur under the new guidelines. If we are not to repeat the same mistakes, it is essential for everyone involved, including legislators and those in the classroom, to demonstrate the ability to think for themselves about what skills children need in order to stand on their own two feet in the society of the future.

Akihisa New education guidelines education junior high school elementary school room to grow Wada Junior High School general studies hours student teacher Shirota assessment academic skills Sugninami training creativity