MOOCs: A Professor's Reflections on Online Education

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Massive open online courses have spread to an extraordinary extent worldwide over the past few years. The most popular of the MOOC platforms is California-based Coursera, which boasts over 7 million registered users and provides courses from leading international schools including Stanford, Yale, the University of Toronto, and the University of London.

In September 2013, the University of Tokyo started offering lectures in English through Coursera. Its first courses were From the Big Bang to Dark Energy by Professor Murayama Hitoshi and Conditions of War and Peace by Professor Fujiwara Kiichi. More than 80,000 students from 150 countries and territories signed up and over 5,000 completed one of the two courses. As well as lecturing, Fujiwara was responsible for overseeing UTokyo’s first online classes. He talked to us about the pros and cons of MOOCs and the divide between universal and local education.

Open Courses Held in English

INTERVIEWER The rise of MOOCs is creating learning opportunities for many who previously were unable to receive higher education. What kind of global impact are these courses having?

FUJIWARA KIICHI One advantage of these courses is that they’re available to anyone with an Internet connection. The Open University of Japan and Britain’s Open University are examples of similar programs open to all, but they provide distance learning via television broadcasts. Taking courses on the Internet allows for a greater degree of freedom, with little restriction on when you can watch course programs.

A second feature is that the classes are conducted in English. Generally, English is the lingua franca of academic research, so there is the advantage that these classes can reach large numbers of students around the world, even in non-English-speaking countries. This isn’t possible with classes in Japanese. Another point is that university classes can usually be attended only by people who have passed the entrance exam and paid tuition fees at the institution where they are given, but this restriction doesn’t apply to MOOCs.

On the other hand, the lecturers don’t know what sort of students will be taking the course until it begins. I thought most of the students for my course would be from Western Europe and the United States, but in fact they came from many other places too, including India, Serbia, and Syria. I think it must have been especially hard to get online in Syria. Looking at the bulletin board discussions that took place alongside the course, I felt the scale and range of participants.

Going Beyond Fixed Notions

INTERVIEWER You taught Conditions of War and Peace on Coursera from October 2013. Why did you choose war as a topic?

FUJIWARA War and peace is a subject where it’s difficult to find a correct answer. In Japan, the mass media is currently painting pacifism and defense of the pacifist Constitution of Japan as a symbol of folly, and rejection of these shibboleths seems to be all that’s required to establish one’s position as a “realist.” However, on the global level the topic of war and peace continues to spark fierce debate. In many parts of the world, war is a part of everyday life and it’s clear that military force is needed to prevent conflict. Armies can bring peace or destroy it; this is the paradox at the center of military power. The topic has the potential for endless expansion.

On the bulletin board, for instance, some students responded to a statement that conflict is inevitable with dissenting views including specific examples. Others put forward the idea that countries don’t have permanent allies, only permanent interests, or that when considering conflicts, whether historical or recent, it’s necessary to ascertain what sort of conclusion they reached. There were many lively and interesting discussions.

My hope and aim for the course was to make students think for themselves and put them into a position where they had to produce their own answers. I wanted to make it difficult for them to reach a conclusion without going beyond their fixed notions. That’s why I chose this topic. It’s the kind of trick that teachers use in their classes on a daily basis.

No Illusions About the Future of MOOCs

INTERVIEWER MOOCs have reminded us of the power that knowledge can bring. Do you think that power can effectively be applied in the future to conflict resolution?

FUJIWARA I think it would be good if that happened, but I’m skeptical. MOOCs began with the major constraint that they were intended for universities to advertise themselves by providing something for free. Universities can’t make a profit on these classes and it’s almost impossible for them to break even. Furthermore, they can only provide a limited number of courses. In this initial stage, universities are striving to differentiate themselves and display originality in their offerings. But these free samples need to be seen as limited-time offers provided for advertising purposes.

For Egawa Masako, UTokyo’s executive vice president, getting MOOCs started was an absolute priority; all the top overseas universities had them and UTokyo couldn’t be left behind. It was seen as PR for the university. But I personally believe it’s better to hold classes with the instructor and students looking at each other face to face and I don’t think online classes will replace this basic model for teaching at universities. MOOCs will probably just become a set way to supply supplementary teaching materials. If that happens, the online courses will most likely lose a lot of their originality and move toward teaching the kind of material for which it doesn’t matter who the instructor is. In that sense, I don’t hold any illusions about the future of these kinds of courses.

Even so, MOOCs are interesting in the way they let you cross all these boundaries of academic level, country of residence, native language, and ethnic background. There aren’t many places where you can teach people from Syria, Turkey, and the United States on the topic of war at the same time.

The Universal-Local Divide

INTERVIEWER Some people have criticized MOOCs for various reasons. For example, only holding courses in English excludes many students, and access to YouTube is blocked in China. Would you also agree that there’s a difference between the education system in Asia and the West?

FUJIWARA I foresee MOOCs splitting into universal and local varieties. The universal MOOCs will be held in English and their content can be expected to follow a somewhat standardized line—like what we see in Europe, where higher education is being standardized through the Erasmus Program for student exchange. Meanwhile, Japan will probably follow the completely opposite path and become extremely focused on local offerings.

Leaving aside other pros and cons of this approach, education always has the greatest impact when it’s conducted in the local language. However, I don’t think the problem is just that classes are held in English; language alone isn’t creating a barrier for students.

Large numbers of female students are signing up for MOOCs, and a lot of them are interested in other countries and want to boost their careers through jobs with an international dimension. As the labor market certainly doesn’t favor women, they have to seek out new opportunities for changing their environment. This trend also applies to Japan, where women in particular are taking these kinds of courses. Our male students have mainly been retirees, but the many female students are of all ages and highly motivated.

As for the universal-local divide, holding classes in English means limiting the students who can take them. The relationship between universal education in English, as typified by MOOCs, and vernacular education in local languages is extremely complicated and one of today’s biggest issues. For example, schools using English don’t teach that women should wear chadors or something similar to cover their hair and bodies, but this is taught as a matter of course in the Islamic world. It would be terrifying if vernacular and universal education grew further apart to the point where they became completely disconnected.

Unless we take action, Japan may drift toward isolation. While universal classes and scholarship go on in English, there’s a danger of Japan heading in the opposite direction, toward partisan local scholarship based on the thinking, “What do foreigners know about Japan?” China currently represents an extreme version of this form of localism. Language can have a highly powerful impact.

MOOCs may be getting positive coverage, but the clash between universal and vernacular education will remain as a problem. That is to say, the limited vernacular education based on the idea that “the only people who can know about a country are the people who live there” will remain. That makes me uneasy. And I’m not only talking about MOOCs; as an instructor, it’s something I constantly view as a major issue.

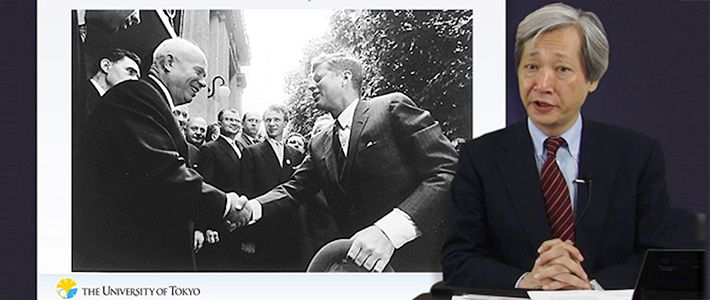

(Based on a May 13, 2014, interview in Japanese held at the University of Tokyo. Banner photo: Professor Fujiwara Kiichi teaching Conditions of War and Peace through Coursera in October 2013. Photograph courtesy of the University of Tokyo.)