Clouds on the Horizon for Solar Power in Japan

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Introduction of Feed-in Tariffs

Ever since the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station in March 2011, there have been strong calls from the Japanese public to rethink this country’s energy policy in a way that places greater emphasis on renewable sources of energy. And just half a year after the accident, in August 2011, a new law was enacted to promote the shift to renewable sources like solar and wind power. Titled “Act on Special Measures Concerning Procurement of Electricity from Renewable Energy Sources by Electricity Utilities,” the law introduced a system of feed-in tariffs, or FITs, for renewable energy.

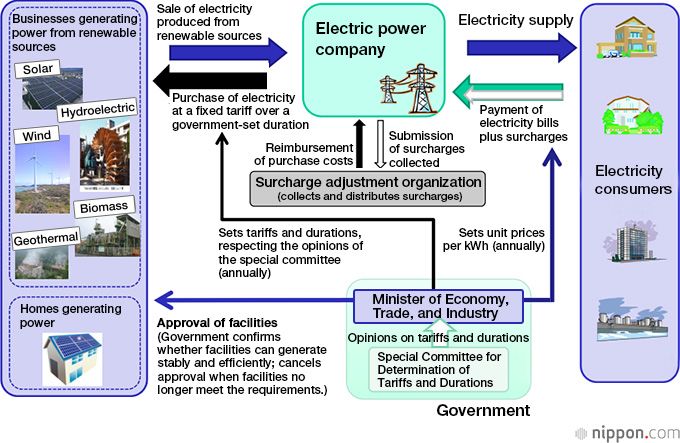

Under this scheme, which went into effect in July 2012, electric power companies are required to purchase all the electricity generated by operators using renewable power sources at a fixed price (tariff) over a fixed duration. The power companies pass their extra costs under the system on to their customers in the form of a surcharge added to the electricity bills paid by households and businesses.

As a means of promoting renewable energy, the current system of FITs had a number of problems from the time of its introduction. First was the concern that because the initial tariffs for the purchase of energy were fixed quite high, the surcharges imposed on users could rise to the point where they produced a widespread backlash. In particular, the high prices and long periods fixed for purchases from operators producing 10 kilowatts or more of solar electricity were seen by many as overly preferential, and there was a widely held assessment that a rising tide of complaints would make it impossible to sustain the scheme.

How Feed-in Tariffs Work

Source: “Feed-in Tariff Scheme in Japan,” a document produced in July 2012 by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry’s Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, p. 3, with editorial revisions by Nippon.com.

Tariffs and Durations under the Feed-in Tariff Scheme (2014)

| Energy source | Category | Tariff (¥/kWh) | Duration (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After tax | Before tax | |||

| Solar | 10 kW or over | 34.56 | 32.00 | 20 |

| Less than 10kW (purchase of excess electricity from homes and other sources) | 37.00 | 37.00 | 10 | |

| Wind | 20 kW or over | 23.76 | 22.00 | 20 |

| Less than 20 kW | 59.40 | 55.00 | ||

| Offshore wind | 20 kW or over | 38.88 | 36.00 | 20 |

| Geothermal | 15,000 kW or over | 28.08 | 26.00 | 15 |

| Less than 15,000 kW | 43.20 | 40.00 | ||

| Small- and medium-scale hydroelectric power | 1,000 kW–29,999 kW | 25.92 | 24.00 | 20 |

| 200 kW–999 kW | 31.32 | 29.00 | ||

| Under 200 kW | 36.72 | 34.00 | ||

| Hydroelectric power systems fitted to existing dams and waterways | 1,000 kW–29,999 kW | 15.12 | 14.00 | 20 |

| 200 kW–999 kW | 22.68 | 21.00 | ||

| Under 200kW | 27.00 | 25.00 | ||

| Biomass | Biogas | 42.12 | 39.00 | 20 |

| From forest thinning | 34.56 | 32.00 | ||

| Wood and agricultural waste | 25.92 | 24.00 | ||

| Organic construction waste (wood) | 14.04 | 13.00 | ||

| Domestic waste (garden clippings, paper, etc.) | 18.36 | 17.00 | ||

Compiled using data from the METI Agency for Natural Resources and Energy website.

Reassessing Measures to Promote Solar Power

Two years after the scheme was introduced, in June 2014, a New and Renewable Energy Subcommittee was set up under the Committee on Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Advisory Council for Natural Resources and Energy (an organ of the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry), to review the FIT scheme. The materials provided by the subcommittee’s secretariat of METI bureaucrats for its sixth meeting, held on November 5, 2014, included the following passages:

The many available sources of renewable energy each present their own distinct characteristics. When aiming to expand the use of renewable energy, is it not important to take these differences into account?

[Progress toward achieving] “maximum possible adoption [of renewable energy]” is assessed on the basis of the amount of electricity generated (in kilowatt-hours), but is it not important to conduct the maximization in a cost-effective manner? And if so, then is it not important to adopt [renewable energy] in a well-balanced manner, taking into account the distinct characteristics of the various sources of electric power—such as by adopting considerable amounts of power generation that can produce more electricity (in kilowatt-hours) with less generating capacity (in kilowatts)?

In the language of bureaucrats, what the repeated instances of “is it not important?” seen in the above passages actually mean is “it is important.” The same document also contained the following figures for electricity generated (in million kilowatt-hours) per unit of capacity (in kilowatts) from various forms of renewable energy over the course of a year: solar, 11 million kWh/kW; onshore wind, 18 million kWh/kW; geothermal, 70 million kWh/kW; small- and medium-scale hydroelectric, 53 million kWh/kW; biomass, 70 million kWh/kW. Geothermal, small- and medium-scale hydro, and biomass were described as “stable” power sources, while solar and wind were described as much more variable. So it seems likely that solar power, with its low, variable output, will be subject to a harsh verdict when the New and Renewable Energy Subcommittee issues the results of its rethink of the FIT scheme.

A Sudden Freeze

On top of this, another new problem has manifested itself even as the New and Renewable Energy Subcommittee continues its deliberations. In order to avoid chaos in the power supply network as a result of a sudden surge in connection applications from enterprises planning or engaged in the construction of large-scale “megasolar” plants to the regional electricity monopolies in Hokkaidō, Tōhoku, Shikoku, Kyūshū, and Okinawa, a temporary freeze was placed on the processing of new grid connection applications from operators generating electricity from renewable sources.

Against this backdrop, at its fourth meeting on September 30, the subcommittee hurried to establish the Working Group on Systems. But regardless of the conclusions at which this new working group may arrive, it is clear that the delay in connecting new facilities to the grid is set to become a dark cloud that obscures the way ahead for the application of the FIT scheme to solar power.

The Need for a Market-Driven Expansion

It is important to remember that although the FIT scheme has presented significant opportunities for the expansion of solar power, it is not in itself a panacea. In a piece in the October 2014 edition of solar industry magazine PVeye, titled “Dependence on FITs Delays Dawn of Renewable Energy Age,” I declared: “When all is said and done, the role of FITs was to provide the initial impetus for solar power. But ultimately solar cannot be considered truly sustainable unless it becomes an energy source capable of succeeding in a market-driven environment. If we truly intend to continue using solar power in the future, it is clear that an energy source that can only expand by imposing a burden on the public simply will not last.” I also expressed this view in “On the Future of Renewable Energy in Japan,” an article in the November edition of Solar Journal; in this piece I offered my forecast of a 2030 energy landscape in which renewable sources (including hydroelectric) command a 30% share.

This does not mean I am opposed to the FIT system. What I want to say is that FIT alone is not enough: We must consider what comes next. It is vital not to forget that a fundamental principle for the successful expansion of solar power is for the process to be market-driven.

Addressing the Problems in the Power Supply Network

By focusing just on FIT in our quest to promote renewable energy, we restrict our potential role models to Germany and Spain. We would do far better to note the example of nations including the United States, Australia, China and the Scandinavian countries, all of which have seen some measure of success in expanding the use of solar and wind power in certain regions through the working of the market mechanism. A feature common to all the places where this has been achieved is the existence of well-developed regional grids for the distribution of electricity.

In Japan too, the key to ensuring a successful future for solar and other forms of renewable energy beyond the use of FIT is solving the flaws in the nation’s energy-supply network. How might we go about achieving this?

Make Use of Facilities Left Redundant by Nuclear Decommissioning

First we should check whether there is actually a shortage of transmission capacity. The focus here should be on the transmission facilities and substations used by nuclear power plants. According to the 2012 revision of the Nuclear Reactor Regulation Act, individual nuclear power facilities are in principle to remain active for no more than 40 years. If this guideline is followed, 30 of the 48 such facilities currently extant in Japan will have to be decommissioned by December 2030. Of the facilities run by Kyūshū Electric Power Company alone, both the first and second reactors of the Genkai nuclear power plant in Saga Prefecture (which went online in 1975 and 1980, respectively) face decommissioning in the very near future, though the plans for the closure of such facilities remain unclear. There is also the matter of the transmission substation currently used by the six reactors at the infamous Fukushima Daiichi plant. Making good use of such soon-to-be-surplus facilities would present a strong platform for a solid expansion of renewable energy in this country.

Install More Power Lines

Another step is to install more power lines. Some suggest that nobody wants to lay power cables because there is no money to be made from them, but is this actually the case? There is no doubt that, in a Japan where there is a clear demand both for the expansion of distributed energy resources (smaller, localized devices to produce and store energy where it is needed) and for an energy system integrated across broad geographical areas, power lines are set to become a bottleneck. And bottleneck equipment is ordinarily a source of considerable profits for those who supply it. The profits from power lines may not be high in terms of yield ratios, but they are sure to be constant and stable. When it comes to the construction of new power lines, it is important to clearly establish not only a framework where the financial markets can correctly assess the potential benefits of any project, but also to build a broader societal understanding in areas where such projects are deemed necessary, as well as to ensure policy-based support for investment in such construction. We must also remember that power companies have the ability to increase the capacity of the grid by improving the performance of existing facilities.

Use More Local Electricity

A third step is to adopt arrangements to obviate the need to transmit electricity over long distances. A nationwide increase in the number of “smart communities” where electricity is produced and consumed locally will decrease the burden on the grid. Another step with the same general aim would be to enhance storage capacity at facilities producing power from renewable resources or at the substations connecting them to the grid. At the point of production, surplus electricity can be used to electrolyze water, allowing energy to be transported to where it is needed in the form of hydrogen. The SPERA Hydrogen System currently under development by Chiyoda Corporation will enable hydrogen to be transported at standard temperature and pressure by mixing it with the solvent toluene. These are all ways to promote the uptake of renewable energy without the need for extensive construction of power lines.

Some of the potential solutions to Japan’s power supply issues that I have described here will take a long time to realize, while others can be achieved relatively swiftly. Working steadily to implement measures of both types and overcome Japan’s power transmission problems while aiming for a market-driven move toward renewable energy sources is the best way to achieve a full-scale expansion in Japan’s use of renewables.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 1, 2014. Banner photo: Photovoltaic cells at a solar power facility. © Jiji Press)

nuclear power electricity energy renewable energy solar power sustainability