Japan’s Employment System in Transition

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

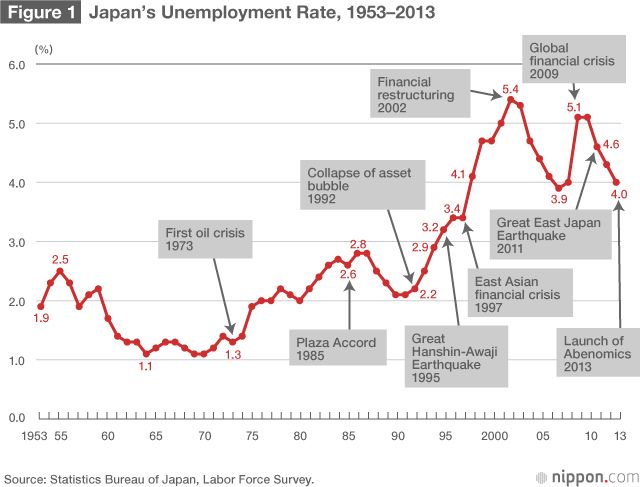

Perhaps the most closely watched of all labor statistics is the unemployment rate, defined as the percentage of people in the total labor force (the sum of the employed and unemployed) who are jobless and actively seeking employment. Figure 1 traces changes in Japanese average annual unemployment rate since 1953.

Throughout the 1960s, the height of Japan’s rapid growth era, the unemployment was very low, staying well under the 1.5% mark. But the period of high-paced economic growth came to a close with the oil crisis of 1973–74, and unemployment began to climb. Later, the Plaza Accord of 1985, which caused the yen’s value to soar, dealt a blow to Japan’s export-driven economy and prompted fears of massive domestic unemployment as Japanese manufacturers shifted to offshore production. In fact, while the unemployment rate for 1986 posted a new high of 2.8%, the government was able to counteract the impact of the Plaza Accord on employment by mobilizing fiscal and monetary policy to stimulate domestic consumption and keep interest rates low.

Postbubble Unemployment

The next major turning point came in 1992, when the collapse of the 1980s asset bubble triggered a sharp rise in unemployment. The 1997 East Asian financial crisis caused another economic contraction, and the following year unemployment hit 4.1% for the first time. From then until 2013, Japan’s average annual unemployment rate fell below 4% only once, in 2007.

In 2002, a new push to restore the health of the banking system by confronting the problem of nonperforming loans led to a round of financial restructuring that temporarily pushed unemployment to 5.4%, the highest rate ever recorded during the decades under review. With the debt problem under control, the employment picture improved again. Then in late 2008, the US subprime mortgage crisis precipitated a financial meltdown and ushered in a recession worldwide, and in 2009 Japanese unemployment soared to 5.1%.

Since then, the jobless rate has fallen steadily. Thanks to growth in the health-care sector, together with emergency job-creation programs undertaken by the Japanese government, the trend continued uninterrupted even after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, and in 2013 the unemployment rate declined to 4.0%.

In 2014, unemployment dipped below 4%, where it has remained every month up through October. As a result, Japan’s annual average unemployment rate is expected to drop to its lowest level since 1997. Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and his supporters have credited the current government’s expansionary policies with the decline in unemployment, but the connection seems dubious, inasmuch as the recent decline began in 2010, three years prior to the launch of “Abenomics.”

Be that as it may, employment ranks with gross national product as a key indicator of economic health, and Japan’s employment picture—especially if judged by the unemployment rate—is healthier than it has been in some time.

The Rise of Nonregular Employment

A key reason the unemployment rate continues to drop is that businesses in most sectors have begun actively hiring again. Indeed, the biggest employment issue facing Japan right now is not joblessness but the growing difficulty employers are encountering in recruiting enough workers to meet their needs.

Still, many critics complain that too many of the new openings are for “nonregular” (temporary or fixed-term contract) employment rather than “regular” (permanent full-time) positions. They argue that nonregular employment offers little or no job security, and as such does little to boost consumer spending and revitalize the economy.

This argument is based on the erroneous notion that nonregular employment invariably equates to job insecurity. In Japan, the category of “nonregular employee” refers to any worker who falls outside the traditional postwar Japanese system of permanent full-time employment. As such, it covers large numbers of long-term contract employees, as well as temporary, dispatched, and part-time staff.

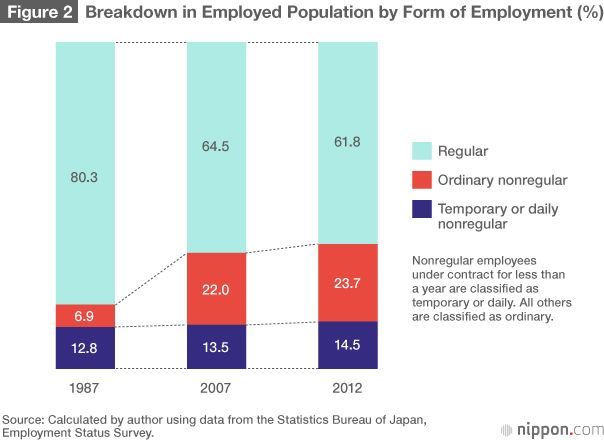

Figure 2 shows the breakdown in the Japanese labor force by form of employment. Following the government’s classification, “nonregular” employees are further divided into “ordinary” nonregular employees, who are hired for a period of a year or more, and “temporary or daily” employees, who work under short-term contracts.

As we can see, regular employees—almost always recruited directly from college—accounted for 80% of the labor force in 1987. By 2007, however, more than one in three employees were nonregular, and nonregulars occupied a still larger share in 2012.

But the chart conveys another key piece of information. It reveals that ordinary nonregular employees, not temporary or daily workers, account for almost all the increase in the share of nonregular employees.

In the economic climate that prevailed after the 1992 collapse of the asset bubble, and particularly in the wake of the 1997 financial crisis, Japan businesses came under intense pressure to cut payroll costs. Their answer was to cut back on the hiring of regular employees, who draw higher wages and limit management’s ability to adjust the size of the workforce as business conditions change.

Still, smooth management requires that a certain percentage of the staff in each workplace consist of long-term employees. Moreover, Japanese companies are aware that the difficulties they currently face in securing adequate staffing will only increase in the years ahead, as Japan’s working-age population shrinks. For this reason, companies value their high-performing nonregular employees and want to keep them on the job as long as possible—hence the growing reliance on “ordinary” nonregular employees working under longer-term contracts. Many companies also offer a path to regular employment for ordinary employees that stay with the company long enough.

Revisiting the Worker Dispatch Act

Nonetheless, the government is responding to concerns about entrenched disparities in the treatment and status of regular and nonregular employees. It hopes to help close this gap by encouraging companies to adopt more flexible systems of permanent employment geared to the diverse needs of employees. Already a few companies offer the option of permanent positions tied to specific jobs and/or locations, allowing employees to enjoy continuity and job security while avoiding disruptive transfers and other harsh job demands frequently imposed on regular employees.

If such options are available, long-term nonregular employees should have more opportunities to transition to permanent positions.

In 2015 the Diet is expected to begin deliberations on a new draft of the revised Worker Dispatch Act, which regulates the temporary staffing industry and the use of dispatched workers in company positions. According to the government, the proposed revisions are designed to expand opportunities for long-term employment by imposing more obligations and scrutiny on the staffing agency, while further loosening the existing three-year limit on the use of dispatched employees in any given job.

Under the amended law, the three-year limit would apply only to the assignment of an individual worker in a given workplace or section. Once an individual worker reached the three-year mark in a particular position or workplace, the staffing agency would be required to take one of several measures to help ensure continued employment, such as formally requesting that the client company hire the worker directly, placing the worker in a new position, or hiring the worker directly on an indefinite basis.

If properly implemented, it could open up opportunities for temporary staff to obtain permanent employee status. The bill deserves calm and objective deliberation in the Diet this time around.

Promoting Employment After 60

Another important focus of Japanese labor policy is the employment of older workers. Japan’s working-age population—defined as those aged 15 and older—is currently 110 million, and a full 32 million of those working-age people are 65 and up. With the population of the younger age groups projected to dwindle further in the years ahead, Japan faces the specter of chronic labor shortages unless it can tap into its underutilized labor resources. In addition to expanding opportunities for women, this means creating a society where senior citizens can continue to work as long as they are willing and able.

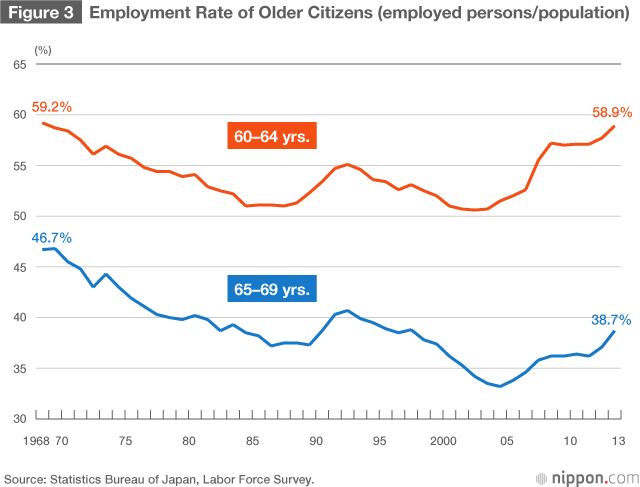

Figure 3 traces changes in the rate of employment among persons in the 60–64 and 65–69 age groups between 1968 and the present.

During the 1960s, when a relatively large portion of the labor force was still employed in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, the employment rate for Japanese aged 60–64 was close to 60%. But as the industrial structure shifted during the period of rapid economic growth, more and more people took jobs that were subject to mandatory retirement. Since most companies set a mandatory retirement age of 55, the employment rate among older citizens continued to decline.

In 1986, the Diet passed legislation encouraging companies to raise their retirement age to 60, and these policies fueled a temporary increase in employment among older citizens during the early 1990s. But earlier trends soon reasserted themselves, and by 2004 only one out of three persons in the 65–69 age group was active in the labor force.

In the years since then, the Japanese government has moved to gradually increase the minimum age for receipt of employee pensions from 60 to 65, a process to be completed by 2030. Since 2012, employers have been legally obligated to offer continuing-employment options until age 65 to retirement-age regular employees who want to keep working. By 2013, the employment rate for persons aged 60–64 was back at the levels that prevailed in the early 1960s. In this age group, the trend toward higher employment can be expected to continue.

Putting the Boomers to Work

Next on the agenda is the challenge of boosting employment among those in the 65–69 age group. If Japan is to maintain the health of its pension system over the long term, it has no choice but to raise the minimum payout age even while cutting benefit levels. This means creating an environment in which people in the mid- to late sixties can earn an income from employment. Fortunately, the rate of employment in this demographic is on the rise. In 2013, close to 40% of this group was employed in some capacity.

The key to making work the norm among Japanese in their mid- to late sixties will lie with the baby boomers, those born between 1947 and 1949. Despite their advancing age, the boomers constitute a huge and influential segment of Japan’s population. According to government statistics, the cohort born from 1946 to 1950 currently stands at around 10 million, outnumbering those born between 1981 and 1985 (still in their early thirties) by about 2.5 million. Going forward, the long-term sustainability of Japan’s social security system and the fiscal health of the nation will hinge on the willingness and ability of people in the former group to continue working into their late sixties instead of retiring en masse to live off their pensions over the next few years.

One way to encourage this trend is by giving older people sufficient economic incentive to work. Under Japan’s current pension system, people between 65 and 70 years of age whose combined salary and pension income exceeds ¥460,000 per month receive reduced benefits. However, to ensure that employment does not lead to a net loss of income, the system deducts only ¥100 in benefits for every ¥200 a person earns over the limit. The government needs to continue building such incentives into the pension system as it promotes expanded hiring of senior citizens. By developing smart labor and social security policies tailored to a rapidly aging population, Japan can provide a valuable model for graying societies around the world.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 28, 2014.Banner photo: Uniqlo explains its new “local regular employee” system to job seekers. © Jiji.)

employment pension Plaza Accord labor retirement Abenomics mortgage