The Burden of Inheritance: An Already High Tax Expands Its Reach

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Forty-Percent Cut in Deductions

Japan’s inheritance tax received a major hike on January 1, 2015. The estate tax was hitherto perceived as a tax for the so-called “haves,” imposed only on the wealthy few, because of a high exemption level.

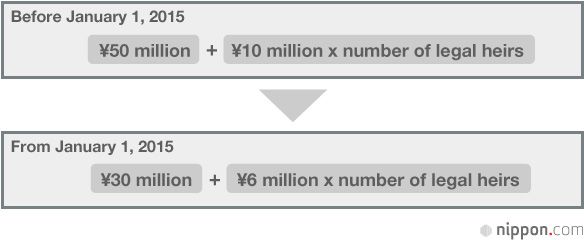

Before revision of the inheritance tax, the total deduction was calculated by adding ¥10 million per heir to a large basic deduction of ¥50 million. If the deceased had two children, they did not have to pay a single yen in inheritance taxes as long as the parent’s estate was within the maximum of ¥70 million (¥50 million + [¥10 million x 2]). Due to this high threshold, inheritance taxes were levied on only about 4% of heirs in Japan.

Under the new system that went into effect on January 1, however, the deduction has been cut back by 40%. In the above scenario, the total deduction would be reduced from ¥70 million to ¥42 million (¥30 million + [¥6 million x 2]). The revision thus brings within the scope of the inheritance tax the assets of a considerable number of individuals that formerly fell below taxable levels.

Adjusting for Disparities or Making Up for Revenue Shortfalls?

The consumption tax went up from 5% to 8% in April 2014, and a further increase to 10% is being eyed as well. It is easy to imagine that objections were raised against the imbalance of boosting a tax that applies to the populace at large while leaving a tax for the wealthy untouched. In this light, the inheritance tax hike may be seen as an attempt to mitigate issues surrounding society’s widening income inequality.

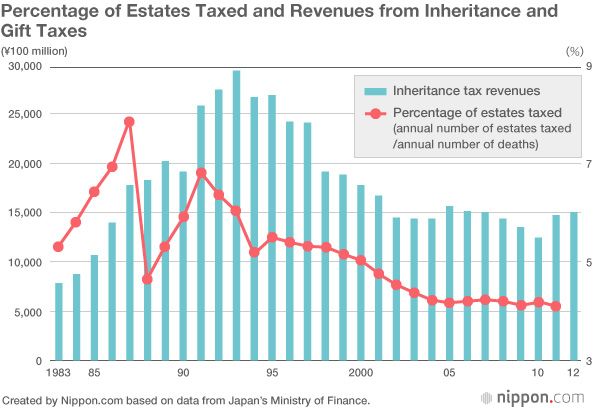

A decrease in the number of taxable individuals along with the bursting of the economic bubble in the early 1990s has significantly lowered inheritance tax revenues. Figure 2 shows trends in the percentage of estates that were taxed and revenues from inheritance and gift taxes, as disclosed on the Ministry of Finance’s website.

Looking at figures from 1983 to 2014, we see that tax revenues have trended downhill after peaking at roughly ¥3 trillion in 1983. They have been hovering at around ¥1.5 trillion over the last several years. In other words, inheritance tax revenues have halved over the 20 years of economic stagnation in Japan—the so-called lost decades. Various factors are involved, but the main reason may be that the market value of land—which often comprises a large part of a person’s assets—has plummeted since the bubble’s collapse.

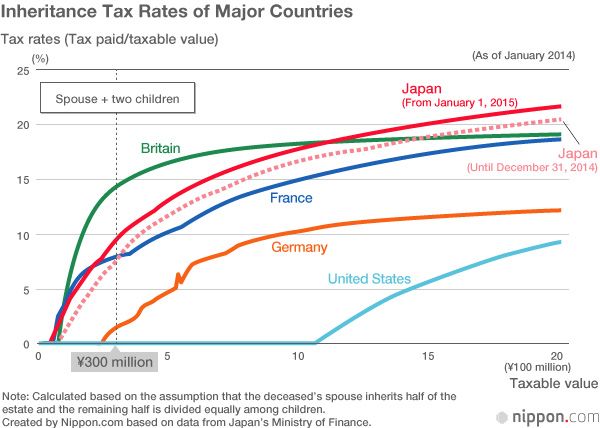

Highest Tax Rates in the World

Some countries in the world have no inheritance taxes. And while many Western countries do, Japan’s tax rates are higher than those of other developed countries. The latest revision brings the maximum tax rate up to 55%, meaning that those in wealthy families may lose more than half of their inheritance to taxes.

The expected response of the rich will be to emigrate to tax havens. It is already not unusual for wealthy people to move overseas, bringing their assets along with them. There are two major factors to relocating overseas:

1. Existence of countries without inheritance taxes

There are many countries and regions in the world that do not levy inheritance taxes, including Australia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Monaco, Singapore, Switzerland, and Thailand. Compared to Japan’s maximum tax of 55%, the absence of inheritance taxes in these countries undoubtedly appeals to the wealthy.

2. Five-year overseas residency requirement

Even if there are countries free of inheritance taxes, it goes without saying that one cannot reap the benefits while living in Japan. Moreover, Japanese inheritance taxes apply to all of an individual’s assets worldwide. In principle, if the deceased had Japanese citizenship, taxes will be levied in Japan even if he or she had been living overseas.

There is a loophole, though. Japanese inheritance taxes are not levied on overseas assets if those leaving and receiving the estate have both lived abroad for five years or longer. For this reason, a growing number of rich people are selling off their domestic assets, transferring their wealth overseas, and moving out of Japan with their families.

Obstacles to Reducing Tax Burdens Through Emigration

However, relocating overseas as a way of lowering estate taxes is not likely to catch on in a big way. The reason lies in people’s attachment to Japan. In particular, those working on the front lines of business often come to feel through their frequent overseas travels that Japan is the most comfortable country for them to live in.

Moreover, many of Japan’s wealthiest belong to the landed class and very few would be daring enough to sell off land passed down from their ancestors and uproot themselves for a new life in a foreign country.

The greatest stumbling block is that not only the asset holders but also their heirs must live abroad for at least five years. While aged parents may be fine basking in retirement overseas, it is a whole different story for their children to leave Japan for five years. If they have careers or children of their own then there will be any number of reasons why they cannot just pack up their well-rooted lives and take off simply for the sake of avoiding a high tax burden.

In light of these factors, the outflow of assets from Japan due to higher inheritance taxes will likely be negligible. Meanwhile, hikes in national taxes and uncertainty in the economic outlook are leading to heightened interest in asset management and protection. A growing number of people are purchasing real estate and investment products overseas, not to save on taxes but to hedge investment risks by diversifying their assets.

Changing Attitudes Toward Asset Management

The January 1 revision of the Inheritance Tax Act resulted in the “democratization” of the tax, meaning that it will now be affecting more families than before. Those living in their own houses in central Tokyo, where land prices are particularly high, will now be subjected to inheritance taxes even if they have little in the way of financial assets other than ¥10 million or ¥20 million in savings.

The Japanese are often derided for their overwhelming indifference to asset investment and tax-saving strategies. But the expanding reach of the inheritance tax, coupled with the rising consumption and income taxes, may discourage more people from keeping all of their financial assets in savings accounts, as has been common. The latest hike in the inheritance tax could serve as a wake-up call for the Japanese to reform their attitude toward asset management.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 9, 2014. Banner photo: A bird’s-eye view of the Sangenjaya neighborhood in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward. With the tax hike, families owning real estate in or near central Tokyo will face inheritance taxes even if they do not have much in the way of financial assets.)

consumption tax Inheritance tax society of disparities tax haven asset management