Tougher Laws No Answer to Money in Politics

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Few Criminal Charges

Since the return of Abe Shinzō as prime minister in 2012, Japanese politics has regained some stability after many years of ineffective and short-lived administrations. A number of cabinet members have been forced to step down since last year over financial scandals, however, casting a shadow on the administration’s future.

Improprieties involving political funds are regarded as a weakness of Japanese politics. They not only sow seeds of distrust among the public but can also cause political turmoil, as was the case following the Lockheed bribery scandal of 1975 and the Recruit insider trading scandal of 1988. An inappropriate response could stir up a controversy big enough to shake the very foundations of an administration.

Blame is often assigned to inadequacies in Japan’s political funding regulations. Despite the plethora of scandals, few politicians are actually indicted or convicted of wrongdoing. Instead, they tend to simply resign from a cabinet or other post to take “moral responsibility” for their actions, and the matter is usually closed. Such practices, though, expose the legal farce that the political funding system has become.

No “Restrictions” on Political Funds

The chief law governing the use of political donations is the Seiji shikin kisei hō (Political Funds Control Law). While kisei is often translated as the verb “control,” here its meaning is closer to “correct.” The purpose of this legislation, in other words, is not to regulate or restrict the flow of political funds but to ensure that such funds are properly managed. Herein lies the biggest shortcoming of Japan’s political funding system.

The financial scandals that have hit the Abe cabinet since last year have focused on the improper use of political funds, but since the thrust of the Political Funds Control Law is on the collection of such funds, it has few provisions on their uses.(*1) This is why politicians and their parties are seldom, if ever, held liable for inappropriate uses of political funds.

While the law prohibits, in principle, political donations by loss-making companies and those receiving government subsidies, politicians are not held liable if they were not aware of those facts. This is a gaping loophole for politicians and their parties that has exacerbated the public’s distrust and outrage.

Sidestepping Legal Liabilities

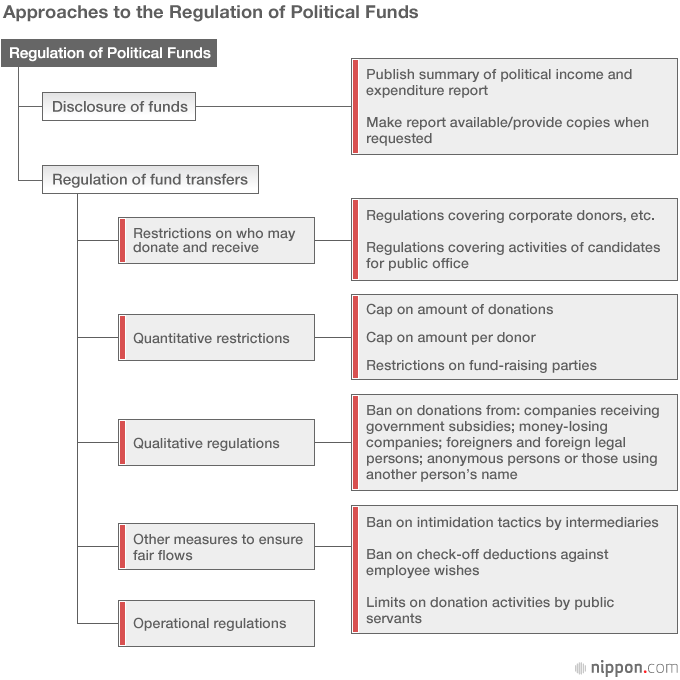

The Political Funds Control Law calls for (1) the disclosure of political receipts and expenditures and (2) the regulation of political fund transfers. The former requires political parties and politicians to submit and disclose a political income and expenditure report every year. The latter contains both “qualitative regulations” describing who may make political donations and “quantitative restrictions” minutely defining the upper limit on the amount that can be donated. In these respects, the law places a cap on permitted donations, violators of which face criminal charges.

As mentioned above, however, politicians are rarely punished, not only because of the many loopholes available but also due to a number of “tricks” that they can employ to sidestep any legal liabilities.

Following revisions to the Political Funds Control Law in 1994 and 1999, individual politicians and the organizations responsible for managing their political funds were banned from accepting political donations from private groups; such funds were now required to go to political parties. But the amendment did not distinguish between party headquarters and local chapters. The chapters were usually headed by a party-affiliated politician, so by donating to a local branch, private groups were, in effect, still able to channel funds to specific politicians, who regarded the chapters as their “second purse.” This made the ban on donations to individual politicians meaningless.

While the law sets upper limits on the amount companies and organizations can donate, they can easily get around this restriction by donating through a subsidiary or other affiliated company. Even companies that are prohibited from making donations can purchase tickets to fund-raising parties or make “personal” donations in the name of an executive. In other words, there are any number of ways to donate above and beyond the amount stipulated by law. As these examples show, the Political Funds Control Law actually does very little to regulate the flow of funds.

Lingering Need for Political Funds

According to the income and expenditure reports published last year, total political funds in fiscal 2013 reached ¥231.5 billion. Why is so much money needed, and why is there no end to financial scandals in Japan? Clues can be found in the country’s unique political and election practices.

The political reforms of 1994 introduced an electoral system combining single-seat districts and proportional representation, giving the party a larger role. This replaced midsized electoral districts, from which several Diet members (usually three to five) were elected, often forcing members of the same party to run against one another in the same district. Consequently, in the case of large parties like the Liberal Democratic Party, the focus of political and electoral activity was on the kōenkai (local support groups) established by each candidate, rather than on the party. Maintaining such groups required massive political funds; indeed, in the early 1990s, total political funds exceeded ¥350 billion.

To be sure, the 1994 reforms reduced the size of electoral districts, and the total political funds required did decline. However, with a few exceptions, most parties lacked the organizational and financial strength to subsidize the political activities of their members, so the kōenkai of individual politicians continued to play a major role. The funding needs of politicians remained unchanged, forcing them to seek out fund-raising opportunities at every turn. A highly porous legal system further contributed to keeping politics in Japan a hotbed of financial improprieties.

The fact that recent financial scandals have been a series of incidents involving single politicians is quite telling. The electoral and political funding reforms of 1994 were aimed at creating a policy-oriented system pitting one political party against another, but the reality seems to be that individual politicians are still the focus of political activity, hindering a clean break from money-related scandals.

Why a Ban on Corporate Donations Will Not Work

What can be done to remedy the situation? Since the problems have focused on corporate donations, a group of opposition parties has submitted a bill to further clamp down on these funds. The effectiveness of such a measure, though, is highly dubious.

Placing a complete, legal ban on political donations from private companies can be done. But this will not eliminate donations from industry groups and labor unions, such as the Japan Medical Association. The JMA has a political arm called the Nihon Ishi Renmei (Japan Doctors’ Political League), to which member physicians make private donations. There are, at present, no limits on the donations that can be made by political organizations, so even if private companies are banned from making donations, political funds will continue to pour in from these industry groups.

It goes without saying, moreover, that donations by corporate executives, managers, or even the rank and file—when made in their personal names—are impossible to restrict. How much sense does it make to ban corporate donations while doing nothing to regulate the flow of political funds from individuals?

A Realistic Look at Supply and Demand

As we have seen, no amount of effort to curb the “supply” of political donations will be effective as long as the “demand” for such funds exists to meet real needs. So a more fundamental solution would be to reduce such needs, which would require a rethinking of the governance of political parties, including the relationship between politicians and their parties.

Problems stemming from the mixing of politics and money are not limited to Japan, of course; they are common in most West-European democracies as well. As such, this is an issue that must be examined in the context of the political system as a whole. For Japan, two decades following the political and electoral overhaul in 1994, now may be a good time to systematically revisit the issue, examining what went well and what did not, and to explore what further improvements are necessary.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on May 4, 2015. Banner photo: Agriculture Minister Nishikawa Kōya replies to reporters’ questions at the Prime Minister’s Office on February 23, 2015, after submitting a letter of resignation. © Jiji.)

(*1) ^ In October 2014 Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Obuchi Yūko’s fund-management organization was reported to have used political funds to purchase baby products, cosmetics, and designer accessories from department stores. Further revelations showed the organization making payments for unexplained trips to the theater, forcing the cabinet minister to step down. She explained that the baby items were gifts offered as a matter of courtesy and that she had not used public funds for private purposes. Her resignation, rather than bringing the matter to a close, ignited further controversy when the fund-managing body of her successor, Miyazaki Yōichi, was found to have used its funds to settle “entertainment expenses” at an S&M club in 2010. —Ed.

Political Funds Control Law political donation donations by companies and organizations party chapter political-fund management organization