Will Lowering the Voting Age Change Japanese Politics?

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Younger Voters

In 2016, the legal voting age in Japan will be lowered from 20 to 18, in time for next summer’s House of Councillors election. The move has sparked much discussion in the media and among political commentators.

As for how the Japanese political landscape could change, the two main questions that the amendment has sparked are, will it prompt new directions in policy by mitigating the influence of the country’s “silver democracy,” and how will it affect the election results.

“Silver Democracy”

The term “silver democracy” was coined to describe the political influence exerted by the elderly—on the strength of the high share of seniors in the population and their high election turnout—which was believed to impede reforms to policies that prioritize their needs. Some argued that a younger electorate would lead to legislators pushing policies that would shift more benefits to the young, while others expressed skepticism in view of the small size of the teenage population and the generally low turnout of young voters.

The idea of silver democracy itself is no more than a hypothesis, though, and as the following facts demonstrate, the preponderance of older voters has not necessarily encouraged a social welfare system that favors seniors.

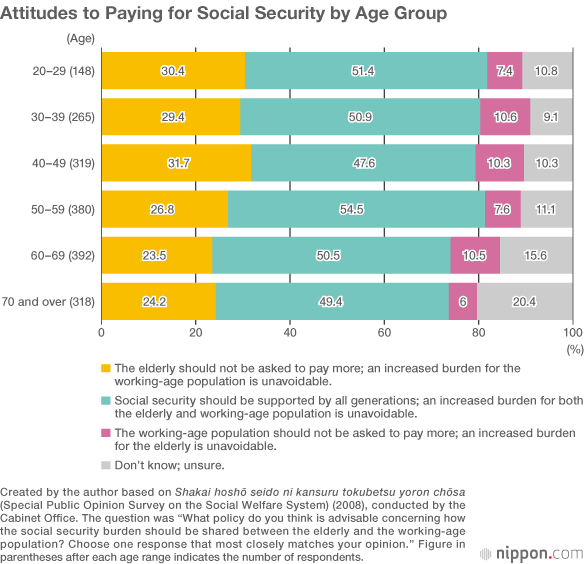

First, the current social security system in Japan was established several decades ago during the high-growth period, when the largest age groups were people in their twenties and thirties and when there were minimal differences in voter turnout by age. Other developed countries with low birthrates and aging populations have social security systems more favorable to the young, contradicting a simple correlation between populous cohorts and bigger benefits. Attitudes toward who should pay for social welfare are fairly similar across generations, moreover, with seniors not wishing to place an excess burden on the working-age population.

The following figure shows the results of a public opinion poll on this latter point. Noticeably, younger people were more likely to say that an increased burden on the working-age population was unavoidable than respondents aged 60 or over. There was no clear generational difference in opinion other than the fact that higher shares of older respondents tended to choose “don’t know.” Such data suggests that a lower voting age will not lead to the election of politicians with different social policy priorities.

Experts commonly talk about “silver democracy” these days as if it were an established fact. The truth is, however, that the high share of older voters is not a significant factor behind social security policies that favor the elderly. There are probably other factors, such as the very small number of female Diet members, the many years that the Liberal Democratic Party—which espouses conservative family values—has been in power, and the seniority-based hierarchy of political parties and the bureaucracy. Whatever the causes, lowering the voting age to 18 will have no bearing on the “silver democracy” argument.

Earlier Political Engagement

So how will voting rights for 18- and 19-year-olds affect Japanese elections? Probably not very much, judging by the fact that this age group represents just 2% of the electorate and that turnout tends to be low among younger voters. Elections may become more volatile in the short term, though, as swing voting among the young was a factor in the wildly fluctuating support enjoyed by political parties in recent elections. But I would like to focus here on the longer-term significance and potential of a lower voting age.

There is less grassroots participation in political activities in Japan than in other developed countries. Few voters take the trouble to speak directly with their representatives or take to the streets to protest; for most people, political activity is limited to casting their ballots at elections. Being able to vote two years younger means an earlier start to political engagement. If this brings with it greater political knowledge and interest, future voter turnout—when these voters reach their twenties and thirties—could rise.

Ages 18 and 19 can be considered the formative years in one’s voting career. There are thus moves within the LDP to require high school teachers to maintain political neutrality in the classroom by legislating strong penalties for violations. But the impact of such a law would be limited, since students will already be in the final year of high school by the time they turn 18. By contrast, almost all college students will have the right to vote; given that around 50% of high school graduates in Japan go on to a four-year university, the repercussions of a lower voting age will be much greater on university campuses.

A Greater Role for Politics at Universities

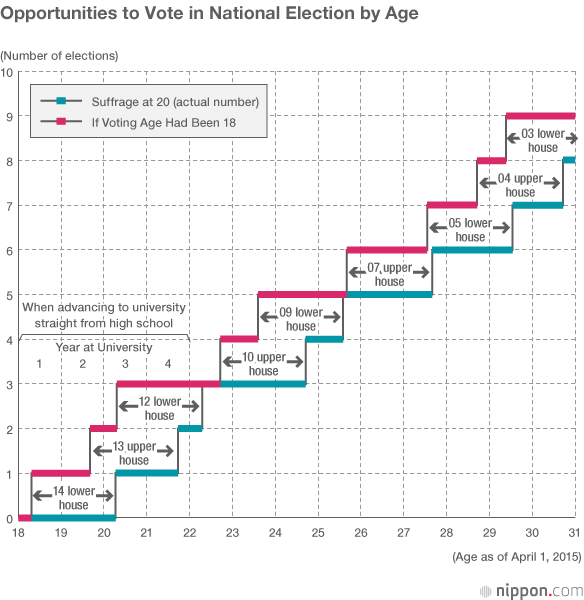

The above figure shows the number of national elections people of different ages have experienced (as of April 1, 2015) since acquiring the right to vote. The blue line is the actual number, while the red line shows what they would have experienced had voting rights been granted at 18. The ages on the horizontal axis are for April 1, 2015, with each gradation including those people in the same academic year (the Japanese school year begins in April). Ages 18 to 22 correspond to one’s undergraduate years at university (assuming advancement to tertiary education immediately after high school).

Overall, the red line runs one or two places higher than the blue line. Thus, if the voting age had always been 18, young people would have experienced one or two more elections. If national elections continue to take place every 18 months or so on average, the lower voting age will essentially mean one or two more opportunities to vote in national elections for younger voters.

The vertical sections of the curve divide those who were old enough to vote in a particular election and those who were not. For example, people born before December 14, 1994, were able to vote in the lower house election of December 14, 2014. This division is represented by the vertical line for the blue curve, to the right of “14 lower house” on the chart.

Since the voting age was still 20 at that time, the line comes during the third year of college. Had the voting age already been lowered to 18, many first-year students—and all second-year students—would have been able to vote, as indicated by the vertical line for the red curve to the left of “14 lower house.” Third-year students may already have taken part in two or three national elections by then.

In short, under the new system, essentially all university students will be eligible to vote, rather than just third- and fourth- year students (along with second-year students with early birthdays). This means that if an election were to take place in the second half of an academic year, the number of potential student voters will increase by over 50%.

Universities may therefore gain greater prominence in the election campaign strategies of many politicians and as venues for political engagement among young people. With all students able to vote, political parties will no doubt give greater attention to winning their support, since securing loyalties while voters are still young could lead to ongoing support for several decades—something that cannot always be said of elderly voters. The lowering of the voting age thus represents an opportunity to get politicians thinking more about the needs of the younger generation.

Reaching Out

Students have hitherto been regarded mainly as staff workers or volunteers during election campaigns, and, with few exceptions, efforts have not been made to reach out to them as constituents or as party members.

This is because, in most major parties, individual politicians have been left to build electoral campaign teams and find backing on their own. Since university students have had little interest in politics or voting, have often not changed their registered addresses and thus cannot vote in the electoral districts where they are now studying, and are likely to move again after graduation, politicians have had little incentive to actively engage them or invite them into their party organizations. Given this state of affairs, their parties need to undertake the bulk of the outreach efforts. Most party organizations are weak, however, and little organized attempt is being made to broaden support among students and other young people.

An even bigger weakness in rounding up grassroots support has been the inability to attract voters—regardless of age—with a coherent set of policies. Voting patterns continue to be dictated by occupational or workplace interests and community ties. Such strategies are effective only when voters have fixed jobs and dwellings; they have almost no meaning for university students. On the other hand, building a network of young, likeminded cohorts is a task that can be better advanced precisely through an elucidation of policy goals.

Politicians and the media will no doubt begin giving greater thought to the kind of policies that appeal to younger voters. This is a task that that will require talking directly to young people, getting them involved in grassroots activities, and working with them to come up with policy solutions. Political parties today are not doing enough to build policies from the ground up, relying instead on bureaucrats, experts, and other elites with specialist knowledge to provide answers from on high. This is one reason for the rift between politics and people on the street.

Whether politicians and parties ultimately seize the opportunity that the lowering of the voting age provides depends on being able to reduce this gap and win back voters’ interest and expectations. Suffrage at 18 in itself will not be a solution, but it can prompt important changes in the activities, organization, and awareness of Japan’s political parties.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on August 24, 2015. Banner photo: Second-year high school students take part in a mock vote on security legislation at Ritsumeikan Uji Junior High School in Uji, Kyoto, on July 8, 2015. © Jiji.)social security aging population politics elections right to vote silver democracy low voter turnout university students