Child Abuse on the Rise: Exploring the Societal Factors

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

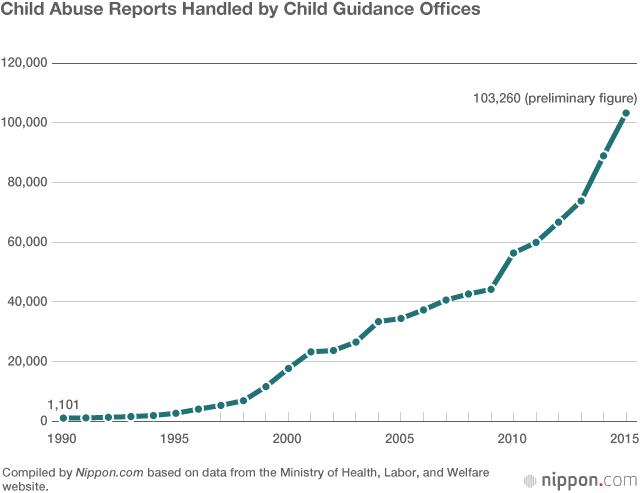

In August 2016 the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare issued preliminary figures for the number of child abuse reports to which child guidance offices responded nationwide from April 2015 to March 2016. The total was 103,260, topping 100,000 for the first time. The number of reported cases was 1,101 in 1990, when statistics were first compiled, and a hundredfold increase is extraordinary to say the least, the passage of 25 years notwithstanding.

Municipal governments are also required to respond to reports of child abuse under the revised Child Welfare Act of 2005. From April 2014 through March 2015, municipalities across Japan handled roughly 88,000 cases. Although there may be some overlap between the two figures, the fact remains that child guidance offices and local governments attend to well over 100,000 cases annually. The situation is very grave.

Disproportionate Prevalence of Psychological Abuse

According to the latest statistics, psychological abuse comprised 47.5%, or nearly half, of the reports received by child guidance offices. It was the most commonly reported of the four types of abuse, the others being physical abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse. Psychological abuse in this context refers to language or behavior by a parent or other caregiver that negates a child’s worth, such as “I didn’t want you to come into this world” or “We would be a happy family if it weren’t for you.” This kind of abuse is harder for others to detect compared to physical abuse and neglect.

This may give the impression that psychological abuse accounts for an overwhelming majority of child abuse in Japan. In fact, however, the prominence of this figure is a consequence of classifying the witnessing of domestic violence as a form of psychological abuse.

The main culprit behind this state of affairs is the definition of psychological abuse under the Act on the Prevention of Child Abuse. The 2004 revision of this law expressly states that witnessing domestic violence is tantamount to psychological abuse for a child. Accordingly, the National Police Agency instructs prefectural police to notify a child guidance office if there are any underage children between partners in a case acknowledged by police as involving domestic violence.

As a result, the percentage of psychological abuse in Japan’s statistics is disproportionately higher than those of Western countries, precluding an accurate understanding of the state of psychological abuse in Japan. It is also impossible to make effective comparisons with statistics on abuse overseas. To remedy the situation, the question of how to treat the data on children’s witnessing of domestic violence needs to be urgently addressed.

By way of comparison, Child Maltreatment 2013, a US report based on data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System, notes that 679,000 victims of abuse and neglect were confirmed by child protective services agencies across the United States in 2013. Of these, 79.5% were subjected to neglect, 18.0% to physical abuse, and 9.0% to sexual abuse; victims of psychological abuse were the smallest group, accounting for only 8.7% of the total.

Incidentally, the US report compiles data on children who may have witnessed domestic violence in a separate category from the four types of abuse, under the heading of “children with a domestic violence caregiver risk factor.” Of the 464,952 child maltreatment victims reported in 36 states, 27.4%, or 127,519 victims, fell in this category.

Misconceptions Surrounding Child Abuse

Subtracting the number of psychological abuse cases from the total reported in the health ministry statistics, cases of abuse of the other three types numbered 54,567. Physical abuse was the most common of the three, at 54.5% of the subtotal. This was followed by neglect, accounting for 44.8%, while sexual abuse came to 2.8%. Comparing these figures with the US statistics, physical abuse would appear to be more prevalent in Japan and neglect and sexual abuse less so.

But this is more likely an outcome of underestimating the frequency of neglect and sexual abuse than a reflection of things as they are. Part of the reason why neglect cases are underestimated may be the misconception that neglect rarely leads to death. Another problem is ignorance on the part of officials of the authorities responsible for handling cases of neglect. Given that chronic neglect exposes children to the risk of serious consequences, such as nonorganic failure to thrive, this is a situation that we cannot afford to overlook.

In Japan, moreover, most of the reported cases of child sexual abuse involve adolescent victims, and there is little data on sexual abuse of younger children. There appears to be a preconception even among child welfare professionals that the targets of sexual abuse are limited to adolescent and older females, hindering an accurate grasp of the full picture.

The Implications of the Leap in Reports

As we have seen, Japan’s statistics on child abuse are plagued with problems. Still, it is remarkable that reports have increased exponentially from just over 1,000 to more than 100,000 in the quarter of a century since the statistics were first compiled in 1990.

Two factors account for this upsurge, the first being changes in public attitudes. It was once the norm in Japan for the community to stay out of problems involving violence and other abuse within the family, regarding them as “family affairs.” But today violence is increasingly seen as requiring societal intervention, even if it is between family members. Such changes in societal attitudes led to the Act on the Prevention of Child Abuse in 2000. This in turn triggered changes in people’s attitudes, resulting in a higher number of abuse reports.

This chain of events alone is not enough, however, to explain the sharp rise. We must presume that a second factor is involved: an actual increase in the frequency of child abuse.

The Demise of the Nuclear Family

Empirically analyzing the sociopsychological factors underlying the growing frequency of abuse is next to impossible. But among the variety of conceivable factors, one that merits attention is the declining ability of families to care for their children. A number of social indicators point to such a decline:

- An increase in marriages preceded by pregnancy and a high divorce rate among those marriages

- A marginal increase in the number of teenage mothers

- An overall rise in the divorce rate

- An increase in single-mother households comprising a young mother and infant(s)

- A high poverty rate among single-mother households

These phenomena point to a shift or growing deviation from the “standard” of the nuclear family, which emerged in Japan in the second and third decades of the twentieth century and steadily gained dominance up through the postwar period of high economic growth.

We can hypothesize that this shift has brought about a serious decline in the caregiving abilities of families, contributing to a greater frequency of abuse. It should be noted that societal factors are also involved in this decline. For instance, because current forms of societal resources and support for families are predicated on the norm of the nuclear family, they often do not reach families with problems like those given above.

Turning the situation around requires such efforts as setting up new mechanisms of societal support for the growing number of young single-mother households. By implementing practical measures, moreover, it should become possible to nip abuse in the bud.

Getting a Handle on Child Abuse

Above I have examined the current state of child abuse in Japan and speculated on the factors contributing to its increase based on published statistical data. But new traits have been observed that are not discernible from these statistics: an increase in instances of shaken baby syndrome, or abusive head trauma, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy.

Shaken baby syndrome is a form of abuse whereby vigorously shaking a baby who will not stop crying causes cranial hemorrhage and other serious conditions. In Munchausen syndrome by proxy, also known as medical child abuse, a caregiver either fabricates or deliberately causes symptoms in a child, leading repeatedly to unnecessary medical testing and treatment.

To the best of my knowledge, no hard data exists indicating increases in these types of abuse. But anecdotal evidence reported by clinical professionals tackling child abuse points to a rise in the incidence of such cases. We have yet to gain a complete picture of the state of child abuse in Japan. Along with a thorough analysis of the reality of child abuse, including what the data does not reflect, Japan must make further clinical efforts to reduce the psychological trauma of child victims.

(Originally published in Japanese on January 10, 2017. Banner photo © Aflo.)