Spotify Aims to Revitalize Japan’s CD-Dominated Music Market

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Green Ships

Spotify, the world’s largest paid music-streaming service, launched in Japan on September 29, 2016. This was four years after the Swedish company first established a Japanese subsidiary. The launch actually ended up taking over five years, as the company had started sounding out record companies and other partners in the country even before beginning its service in the United States in 2011. In the intervening years, Apple Music and Google Play Music began their services worldwide, including in Japan, while domestic competitors Line Music and Awa entered the Japanese market alongside KKBox of Taiwan. An early bird elsewhere, Spotify is a latecomer in Japan.

The delay was caused by wrangling with record companies. Confident about the quality of its service, Spotify insisted on a “freemium” model, where a basic package is available for nothing while paid subscribers get improved features. The idea of giving something for nothing was hard for Japanese labels to accept. Spotify also places importance on providing its users with a wide selection of music, so it was unwilling to launch without songs from the major labels.

In Japan, powerful foreign businesses entering the market are often compared to the “black ships” of US Commodore Matthew Perry, a symbol of the forced opening of the country from its self-imposed isolation in the mid-nineteenth century. I heard that Spotify played on this association by having its representatives bring origami ships in the color of its logo, saying, “We’re not black ships. We’re green ships.” Its company culture is one of considering local conditions and meeting them halfway.

The Japanese record industry has also become more actively involved in streaming since last year. Sony Music, Avex, and Universal Music are among the financial backers of Line Music, launched by the company Line in the wake of the huge success of its texting app. Awa, meanwhile, was jointly established and developed by Avex and major tech firm CyberAgent. This has led to an atmosphere where, rather than turn Spotify down, the industry is willing to choose reinvigorating the music market as a whole.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek talks at a press conference in Tokyo on September 29, 2016. The company launched its service in Sweden in 2008; Japan has become the sixtieth country in which it operates.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek talks at a press conference in Tokyo on September 29, 2016. The company launched its service in Sweden in 2008; Japan has become the sixtieth country in which it operates.

What Makes the Japanese Market Different?

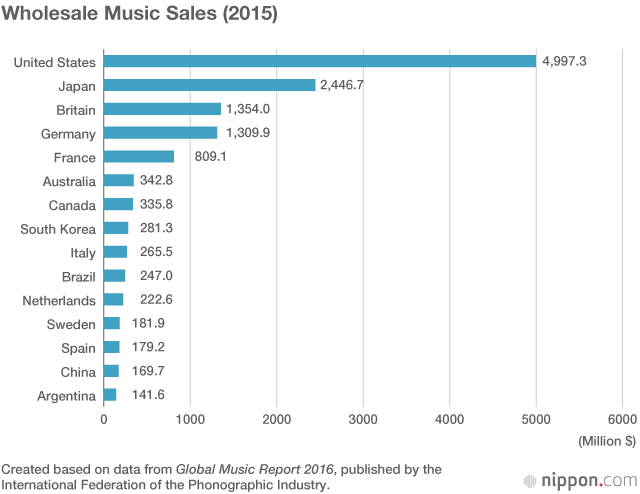

Before thinking about how Spotify will affect the Japanese market—the second biggest in the world—I would like to list some of the factors that set it apart from other countries.

1. A Large Physical Media Market

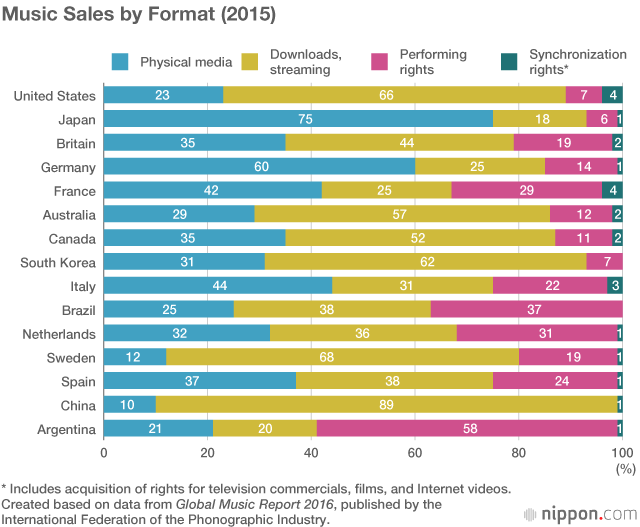

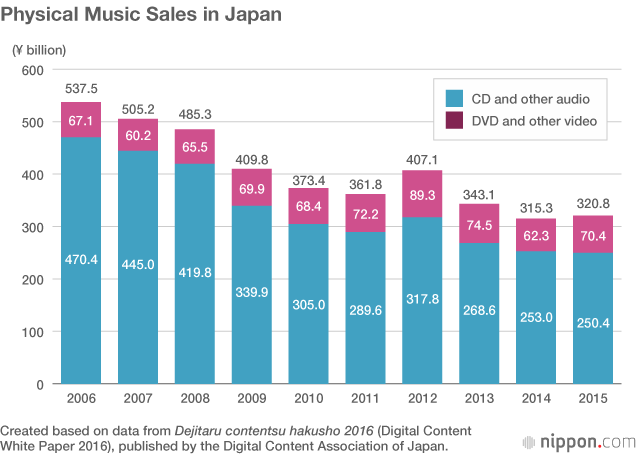

In 2015, Japan’s market for physical music media, including formats like CDs and DVDs, was worth ¥320 billion. Although this market has been on a downward trend in recent years, it still overtook the corresponding US market to become the world’s largest in 2009. Physical formats dominate in Japan with a 75% overall share—considerably higher than in other countries.

Government regulations for maintaining prices and special arrangements between record companies and distributors support the market. In Japan, there is a list price for CDs set by the manufacturer to ensure that they cost the same in every store. This is similar to arrangements for books and newspapers, although with CDs it only lasts for a limited period. The average price of a new album is ¥3,000, which is about two and a half to three times more expensive than in the United States. The packaging and booklets, including liner notes and lyrics, are beautifully produced, and the sound quality is reliable. But from an international perspective, CD prices in Japan are exorbitant.

Another strength for the physical market is the nationwide network of specialist CD stores. Outlets like these have all but disappeared from the streets in many parts of the world, but Japan still has four major chain stores: Tower Records, HMV, Tsutaya, and Shinseidō. There are also regional chains and CD corners at general goods stores like Village Vanguard. Generally, CD stores contract with record companies for direct supplies of product, taking a uniform cut of sales. They share detailed information on titles and build mutually beneficial relationships. Although this cozy arrangement has come under some strain in recent years, it is one reason for the continued popularity of physical media.

It is impossible to discuss physical sales without also mentioning the “AKB strategy.” For some time now, Japan has been home to marketing encouraging core fans to buy multiple copies of the same material. Various forms of DVDs and other extras might be included with special-edition initial pressings of CD singles, for instance. This was how things were done when the first week’s position on the Oricon weekly chart, based on sales of CD singles, was the main indicator of whether a song would be a hit.

The AKB strategy has taken this approach to extremes, driving CD sales by ardent fans by including tickets that can be exchanged for individual handshakes with idols from AKB48 and its sister groups at special events or used to vote in “elections” to decide the standing of members within the group. It is not unheard of for one person to buy several hundred copies. The excessive importance formerly given to the Oricon chart encouraged this excessive tactic. The practice of buying up large numbers of CDs to acquire voting tickets and selling them to secondhand shops or discarding them is a social problem that will perhaps be addressed at some point.

2. CD Rentals

Global digital music distributors like Apple’s iTunes Store have not really caught on in Japan, largely due to CD rentals. Lending music has been legal since the analog record age, with rental stores spreading across the nation in the 1980s. Regulations from industry organizations have remained unchanged from a time when records could be copied onto cassette tapes, through the introduction of CDs, to when music could be ripped to computers as digital files. In 1989, there were more than 6,000 rental stores; although they have become less common, there are still over 2,000 in 2016. Low prices helped iTunes win popularity overseas, but in Japan it is possible to rent albums and singles for around ¥300 and ¥200, respectively, making this potentially a much cheaper way to acquire high-quality digital tracks than downloading them from iTunes. The habit of renting CDs and DVDs from nearby stores became common, especially among young people, delaying the adoption of Internet purchasing.

Although CD rentals have been an important part of the Japanese music market to date, they are likely to succumb to streaming at some point.

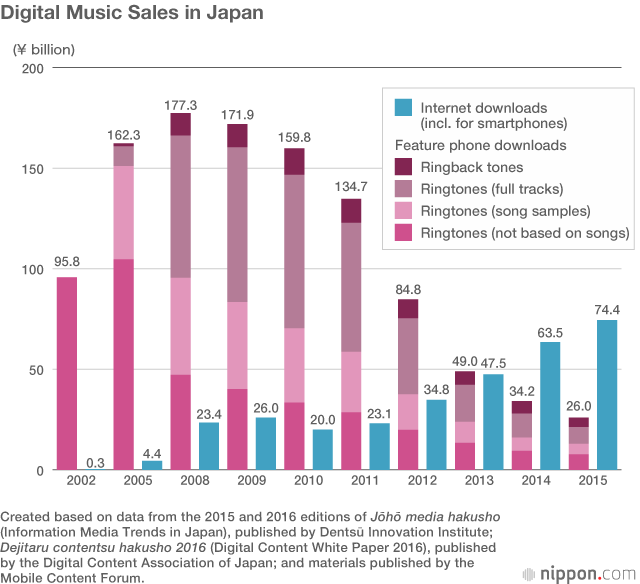

3. Ringtone Market

During the years when iTunes and other digital download services were unable to gain traction, a sizeable market developed for feature phone ringtones based on song samples. Japan is unusual in that ringtones came to dominate the download market for feature phones; in other countries, ringback tones (heard by the caller) were more popular. At first, in 2002, only samples of songs were available, but in 2004 it became possible to download full tracks.

The market peaked in 2008 at ¥177.3 billion, thereafter shrinking rapidly as consumers switched to smartphones. By using download services like iTunes, they could buy songs for ¥150–¥250 instead of the ¥350 cost of full-track ringtones on feature phones.

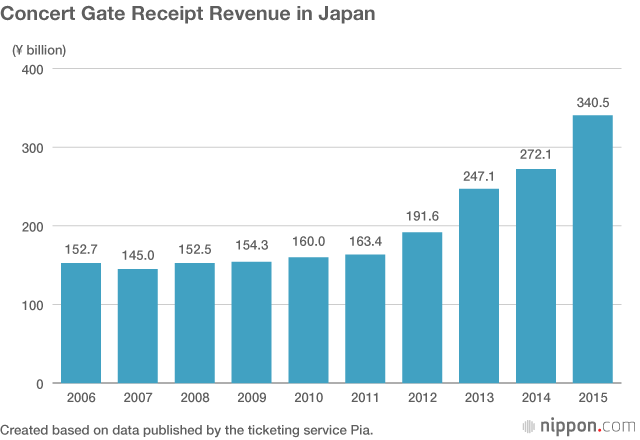

4. A Growing Concert Market

Incidentally, while the music market is stagnant as a whole, the concert market is expanding. In 2015, it cleared ¥340 billion, overtaking the physical media market. This is one sign of Japan’s love for music. The market could expand further if the industry finds a way to benefit from booming tourism figures by attracting international visitors to concerts.

Music and Social Media

As outlined above, physical media have remained a tenacious presence in Japan, CD rental stores have slowed the uptake of digital download services, and a major ringtone market established itself before contracting with the advent of smartphones. A new development in 2015 was the full-scale arrival of streaming services. Now that Spotify has thrown its hat into the ring, will the market change again?

It is well known that Apple set itself in opposition to Spotify and aimed to appeal to the record industry by rejecting the freemium model. In Japan, Google Play Music and KKBox also hoped to stay on the right side of the industry by offering only paid premium services, instead of the freemium models they offered elsewhere. By contrast, Spotify stuck to its identity by launching a freemium model in Japan, even if the design is a little different from that in Europe and North America. This decision may influence other streaming services in the country.

The greatest gift an on-demand freemium service like Spotify will provide for the industry is stimulated communication about music. Streaming services have focused much of their recent efforts on music discovery, playing up their potential for serendipitous encounters with new songs and artists. With its low bar to entry, freemium streaming may be effective in stemming an apparent loss of interest in music among some young Japanese people.

Spotify also allows users to get recommendations from playlists created by musicians and other celebrity influencers. This kind of publicity has helped launch new stars overseas, and we can expect the same to happen via skilled users of Japanese social media. Discovery via streaming services is easily shared on social media, forming still another marketing channel.

For users, joining a streaming service and casually listening to music is a form of consumer activity that has a totally different motivation than buying physical media, which may be done for the enjoyment of building a collection or owning a visible connection with the artist. Streaming services have minimal negative effects on the physical market, while the positive effects from increased encounters with artists have already been demonstrated in Europe and North America. In Japan, where consumers have a strong predilection for physical media, these benefits are likely to be even greater.

As Japanese musicians tend to be cautious, and big names have many stakeholders, many are taking a “wait and see” approach to new digital services. Yet streaming services are not a replacement for physical media, representing rather a more developed form of radio and jukeboxes. Once it becomes clear that these services are a way to capture new listeners and that musicians receive a relatively high share of income, unlike what they can expect from YouTube, it is only a matter of time before more publishers and artists make their songs available.

The launch of Spotify—one of the original music streaming services, enjoying healthy support from the social sharing sphere—is likely to have synergistic effects on the strong network of CD stores and the burgeoning concert scene. I have high hopes for future growth in the Japanese music market.

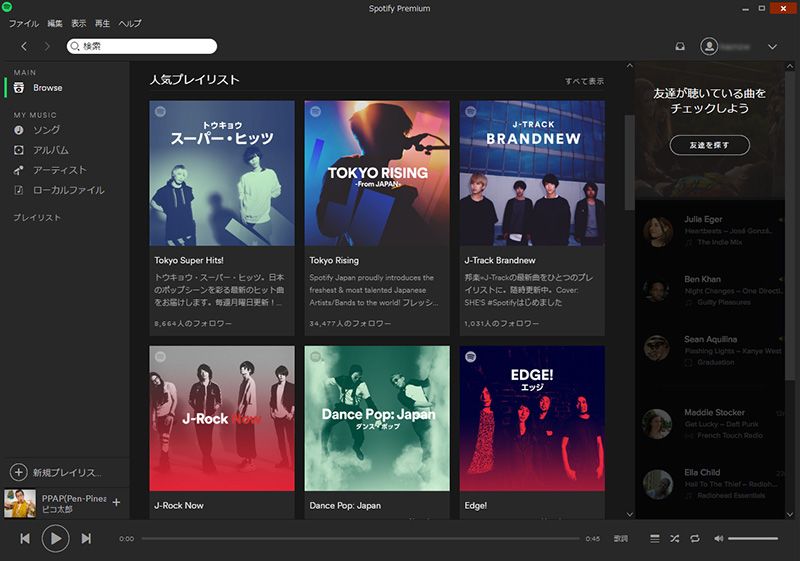

Spotify users can listen freely to over 40 million tracks, including Japanese songs. The free version has ads and reduced functionality, while the premium version—costing ¥980 per month—provides high quality songs without commercials. Like in other markets, the service recommends tracks and playlists to users based on their playback history; as a special feature for Japan, users can display lyrics on the screen while songs are playing. Official Spotify playlists include Tokyo Rising, which introduces Japanese artists to the world.

Spotify users can listen freely to over 40 million tracks, including Japanese songs. The free version has ads and reduced functionality, while the premium version—costing ¥980 per month—provides high quality songs without commercials. Like in other markets, the service recommends tracks and playlists to users based on their playback history; as a special feature for Japan, users can display lyrics on the screen while songs are playing. Official Spotify playlists include Tokyo Rising, which introduces Japanese artists to the world.