Japan Needs a Frank Debate About Capital Punishment

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Choosing Who Lives and Dies

In July 2016, Japan was shocked by the stabbing deaths of 19 residents of a disabled care facility in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture. Public outrage swelled when a letter surfaced that was written by the perpetrator, a former employee of the facility, shortly before the incident. In this, he brashly declared that killing the mentally disabled helped minimize misery and that his actions were for the good of Japan and world peace. People across Japan condemned the killer for his eugenic thinking, proclaiming that all life has meaning and that no person has the right to choose who should live and who should die.

I agree that all human life is precious. It defies being ranked or quantified. Yet, if the public outcry we heard after the Sagamihara murders is to be believed, then I am obliged to point out that Japanese society remains willfully ignorant of the eugenic undertones of capital punishment.

The death penalty is the intentional and unnatural taking of human life that a court of law has judged to no longer have meaning or value. In Japan there is broad public support for the system, with more than 80% of citizens approving of judicial executions.

What is important to consider here is not that there is capital punishment in Japan, but why so many people in the country avert their eyes to the reality it represents. People, of course, are cognizant that Japan enforces the death penalty. However, they only give it passing recognition. Hardly anyone in their daily lives ever stops to consider how an inmate is actually put to death, what passes through their mind at the end, or how they spend their final days. More significantly, very few people ever contemplate what having the death penalty means to society.

Aum Shinrikyō on Death Row

For many years my interest in capital punishment was the same as most other Japanese. I felt it was a just and fair punishment for a person who had committed the grave crime of murder. I never questioned why a person who had taken another’s life should also die. My confidence began to waver, however, after I interviewed six leaders of Aum Shinrikyō sitting on death row while I was shooting a documentary about the cult. As I sat and talked with these individuals the reality that I was speaking with people who were waiting to be killed gradually sank in.

Of course, all of us will die someday. Perhaps it will be in an accident, from illness, or simply due to old age. However, these were not to be the fate of the six men I sat speaking to through thick, transparent acrylic panels. These individuals were slated to be legally murdered.

Each of the cult leaders I interviewed said they regretted what they had done in the name of religious fanaticism. Many choked back tears, saying that it was only fair when considering how family members of victims must feel that they too should be killed.

I met with them many times. We also exchanged letters. When we talked, their words were not always those of regret. There were times when we joked and smiled. When I misunderstood a particular detail of their crime one might shout reproachfully, “It wasn’t like that at all, Mori!” In short, these men were normal human beings. In some respects you could even say they were kinder and more genuine and upright than many people I had met.

Somehow I could not make sense of it. It is a sin to kill. These men had broken this fundamental human law, and as punishment they would be legally put to death. The logic defied me. I could not understand why they had to die or why society seemed justified in killing them.

This experience led me to begin reporting on capital punishment. In my work I interviewed a wide variety of people and pondered countless aspects as I struggled to gain an understanding of the issue. After more than two years of reporting, I compiled my experiences and thoughts into the book Shikei (Capital Punishment).

Allow me to begin with my conclusion: there is no one overriding, logical argument that justifies the death penalty. Japanese who are in favor of capital punishment like to cite its effectiveness in deterring crime. By this logic, then, one would expect public safety in the two-thirds of the world’s nations that have abolished the death penalty to be in decline. The statistics, however, do not clearly bear this out. In fact, sociological research overwhelmingly shows the death penalty serves no significant function as a crime deterrent.

Many advocates of abolishing capital punishment point to the risk posed by false convictions. Proponents of the system, however, argue that such risks exist for all forms of criminal punishment and that abolishing the death penalty based on such a premise would effectively undermine the very foundation of the criminal justice system.

This is a false argument as the two punishments could not be more different. Incarceration restricts a criminal’s freedom, whereas capital punishment results in their death. While behind bars there is hope that an offender can be rehabilitated and eventually rejoin society. Executing a prisoner eliminates any such chance. Imagine a legal system where the punishment for breaking a person’s arm was to break the arm of the perpetrator. This would be no different than the eye-for-an-eye reprisals of the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi and would hardly be compatible with the spirit of modern jurisprudence. Yet the death penalty is the lone form of criminal punishment that is still based on this ancient idea of retributive justice. Its finality—once carried out a prisoner can never be freed if later found innocent—gives the potential of wrongful conviction weightiness far beyond that of other punishments.

Out of Consideration for Victim’s Families

Ultimately, many death penalty advocates do not rely on logical arguments, but base their position on the feelings of the family of victims. When a heinous killing occurs in Japan, the media is quick to play up the bitterness and hatred of the victim’s relatives toward the attacker. Exposed to this emotionally charged coverage, readers and viewers naturally feel sympathy toward the family, certain they would harbor the same thoughts if it was one of their own loved ones who had been murdered. Seen in this light, the death penalty serves to assuage the grief and anger of the victim’s family. Its justification, then, does not have a logical foundation, but is based on the raw desire for retribution.

Society, of course, must do all it can to help and support family members in dealing with such an incomprehensible act of violence as murder. There is an endless array of issues that families face, many of which can be addressed through social programs providing emotional and psychological care. However, supporting survivors and vengeance against the perpetrator do not occupy the same space. If maturity is responding to calamity in a calm and logical manner, then we must say that Japan has yet to grow up when it comes to considering the death penalty.

When I make the case for ending capital punishment I am often asked if I would feel the same if my own child had been killed. I generally preface my response by acknowledging the sheer impossibility of knowing how I would react, and then follow by saying that instead of the death penalty I would prefer to kill the perpetrator with my own hands.

Understandably, many people are taken aback by this and some even accuse me of having double standards. My response is that it is only natural to have double standards. If my child was killed, I would suffer from the crime too.

It is important that we try to empathize with the victim and their family. Yet it is also important that we acknowledge that we can never truly understand their thoughts and emotions without experiencing a similar trauma in our own lives.

Many family members of victims that I have met are wracked by guilt, even while harboring a strong desire for retribution. They endlessly berate themselves, asking such questions as “Why did I let you go out that night?” or “Why did I take my eyes off you?” These are the things that while kneeling alone in front of the family Buddhist altar they repeatedly wail to their lost loved ones. Carrying such remorse must be a living hell. People who support the death penalty, however, have no way of understanding such heartrending agony. Even as they tell me in voices quivering with emotion how they understand the feelings of the survivors, all they can really relate to is a banal desire for revenge.

The truth is that more than half of all murders in Japan are committed by family members. In such situations it is difficult for others in the family to speak out, and the media, too, tends to tone down its coverage. As a result, a majority of murders in Japan go unnoticed by the public, and very few people are even willing to imagine that surviving family members of these killings exist.

Again, if one is going to hold up the feelings of family members as a pillar for maintaining capital punishment, then should we not seek a lighter sentence if the victim has no immediate family? This is not logical, of course, but such crimes actually occur. If such exceptions were made, however, the very cornerstone of modern criminal justice would collapse. In short, emotion would defeat logic, a situation that would invite innumerable legal inconsistencies. The 80% of the population who support the death penalty choose to remain oblivious to this contradiction. Instead of honestly and logically considering the issue, they avert their eyes. This is where Japan stands today regarding capital punishment.

France as an Example

It has been said that there is no other country in the world where it is so easy to generate a boom or create a bestseller than in Japan. Said another way, Japanese have a strong tendency to follow those around them. Extreme centralization coupled with a propensity toward blind obedience makes for a powerful predilection to submit to the decisions of those in power. I feel that these national traits and Japan’s refusal to let go of capital punishment are by no means unrelated.

France, one of the last European nations to abolish capital punishment, is a perfect example of how popular support for the death penalty can change. Public sentiment was strongly in favor of capital punishment prior to the government ending the practice. French leaders did not let popular support sway their decision, and once they moved to stop executions, public consciousness shifted.

The question Japanese leaders must consider is what brought about this change. Quite simply, French citizens found that abolishing the death penalty had no adverse effects to the peace and order of society. Numerous other countries have come to the same conclusion by putting logic ahead of emotion and abandoning this archaic form of punishment. It would be a tall order, however, to expect the Japanese government to come to such a decision as there are far too many legislators who fear that they might lose the next election if they call for ending capital punishment.

Market principles—these might be characterized as a form of populism—are extremely powerful in Japan and are reflected in the way the Japanese mass media cover the news. The media tend to select information that will have the broadest appeal—out and out fabrication is also not unheard of. When a crime is committed, the media zooms tightly in on the rage and sorrow of family members as it boosts ratings and sells more newspapers and magazines. The first priority of the media is to reduce a story to its base elements, making it easy for the public to understand and digest. Any difficult, logic-based arguments are swiftly rounded off to make a clean, simple story. This appeal to raw emotion drives support for the death penalty by making the execution of criminals appear as a “just” punishment.

An Overdue Debate

The fact of the matter is that the Japanese public has almost no access to information about capital punishment. Japan and the United States are outliers among developed nations in their continued use of the death penalty. However, one aspect where they diverge is that America makes information about executions public. Representatives of the media are present when a death sentence is carried out, and many states also allow relatives of the victim and perpetrator to view the event. In this way the American public is exposed to the reality of capital punishment and is able to frankly consider the moral and legal implications. Having an open and public debate on the issue has led a number of states to abolish or impose a moratorium on executions.

In sharp contrast, it is unimaginable in Japan to allow media or family members to be present during an execution. And as a result, the Japanese public is not forced to have a candid debate of the issues.

The consequence of this is that Japan still carries out death by hanging, a method it officially established for executing prisoners back in 1873. Hanging does not exact a swift and painless death, and many inmates struggle in agony for long minutes before they finally expire. But the public does not seem to be interested in this fact. In America, states have changed how they carry out executions, moving from hanging to the electric chair to lethal injection. Information about capital punishment being made public has brought about this shift by sparking debate among average citizens. The conversation in the United States now wavers between continuing or abolishing capital punishment.

If the Japanese media were performing its duty, it would demand that the Ministry of Justice disclose more information about executions. But as the Japanese public is willing to remain ignorant, the media does not pursue the issue as it should. This has long been the status quo.

The situation must change, however. First, information about the death penalty must be made publicly available in order to spur debate. Only when this happens will citizens have the capacity to honestly contemplate whether the system works, its risks, the thoughts of inmates as they face death, and the social repercussion of maintaining a system of capital punishment.

If after this debate Japan decides to keep the death sentence, then I will accept that decision. For the time being, however, I will continue working to pull back the curtain on capital punishment and bring balanced debate to Japan’s lopsided approach to the death penalty.

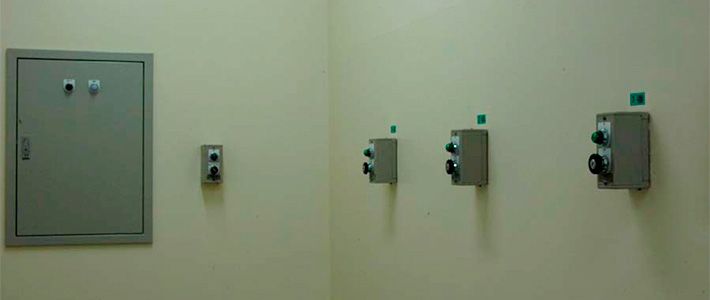

(Originally published in Japanese on December 27, 2016. Banner photo: The control buttons in the execution chamber at the Tokyo Detention House. The three buttons pushed simultaneously open a trapdoor to execute a condemned prisoner by hanging. The use of three buttons disguises which jailor releases the trapdoor. © Ministry of Justice/Reuters/Aflo.)