A New Shopping Center for a Tsunami-Struck Town

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Crowds Gather Once Again

On March 3, 2017, the Minamisanriku Shizugawa Sun Sun Shopping Village opened for business. Located in Minamisanriku, a coastal town in Miyagi Prefecture that was devastated by the March 11, 2011, Great East Japan Earthquake and ensuing tsunami, this shopping district replaces a temporary facility that opened in February 2012. With permanent shops in place, the town now hopes to regain the vitality that comes from having a central hub for residents to do their daily shopping.

The famed architect Kuma Kengo designed the bright wooden structures, built with Japanese cedar wood harvested right here in Minamisanriku.

The famed architect Kuma Kengo designed the bright wooden structures, built with Japanese cedar wood harvested right here in Minamisanriku.

March 3—a date that can be pronounced san san in Japanese, echoing the name of the shopping center—was cold, with a biting wind, but the Sun Sun Shopping Village was crowded with locals and visitors from out of town. Abe Tadahiko, who heads the district’s shop association, beamed as he looked at the new shops on their first day of business: “For six years since the disaster we’ve worked so hard to reopen our stores. It’s a wonderful feeling to see this reopening day come at last.”

A Higher Home for the New Shops

Six long, single-floor wooden structures make up the new, 28-shop district, which stretches across a plot of land located some 600 meters closer to the sea than the temporary shops residents have used for the last five years. Construction costs totaled some ¥700 million, around ¥500 million of which was covered by government reconstruction funding. Twenty-three shops have moved from the temporary facility to their new, permanent location, along with five new entrants.

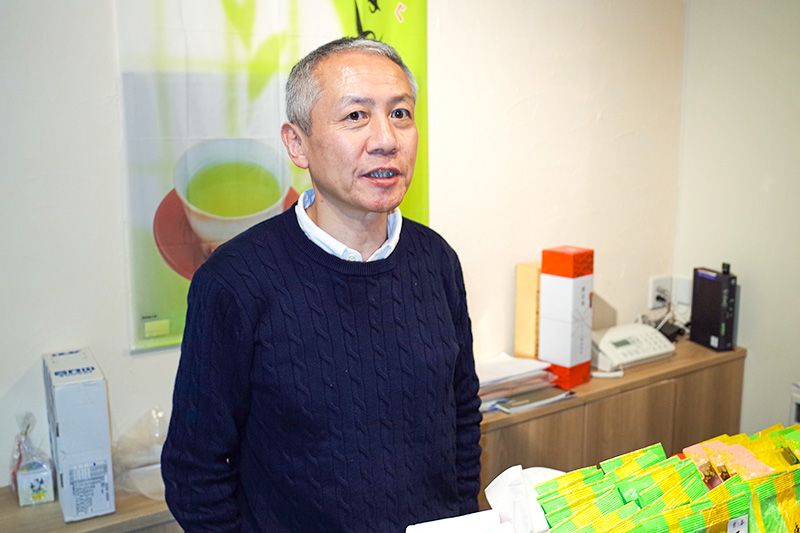

“It’s a relief to be open at last,” says the district association chief, Abe Tadahiko.

“It’s a relief to be open at last,” says the district association chief, Abe Tadahiko.

Abe, who operates Abe Chaho, a tea and confection shop, talked of the business owners’ determination to succeed in their new location. “We’re finally at the real start line. We face plenty of problems in this tough business environment, but we’re ready to come together in our efforts to prosper and meet the needs of the town’s residents.”

I spent time in Minamisanriku soon after the 3/11 disaster, as well as two years later, in March 2013, when I chronicled my visit for this site. Today the town presents a completely different face, with dramatic progress in the construction of public housing units along the hills inland from the sea. The earth excavated from those hillsides to make room for homes has been trucked down to the town’s devastated lowlands and piled into tan pyramids flattened at their tops.

The Sun Sun Shopping Village stands around 10 meters above sea level, atop one of these platforms. To the west of the shops, tucked into the valley between raised spaces, is the reinforced frame of the only former town office building to remain in place after the 15-meter tsunami swept through the community. This twisted metal structure is being preserved as a reminder of the 3/11 destruction.

Some of the raised platforms near the new shopping area. At right is the red frame of the only town office building to remain standing after the tsunami hit.

Some of the raised platforms near the new shopping area. At right is the red frame of the only town office building to remain standing after the tsunami hit.

No Smooth Sailing Ahead for Business Owners

Abe Takekazu, the fourth-generation proprietor of the bakery and pastry shop Yūshindō, has relaunched his business in a shop around twice as large as the space he was using when I interviewed him four years ago. He remains concerned about prospects for his business, though: “We face a tough climate today, just as we did in 2013. The key will be whether we can maintain steady sales during the off season, when we don’t see much tourist traffic. We can’t just sit around waiting for shoppers to come to us—we’ve got to think up ways to improve business during the dry spells, such as delivery-based sales to take our products to where the customers are.”

Abe Takekazu’s Yūshindō bakery was founded in 1910. Its showcases are packed with a delicious variety of sweets and baked goods.

Abe Takekazu’s Yūshindō bakery was founded in 1910. Its showcases are packed with a delicious variety of sweets and baked goods.

Abe’s worries appear well-founded. Unlike when he sold from the temporary shopping center, where rent was free, his new location costs around ¥200,000 a month to lease. He is also responsible for paying wages to his employees. All this weighs heavily on him, but he is determined to soldier on.

One shopper I spoke with was Hasunuma Akira, who was visiting Minamisanriku from the Miyagi Prefecture town of Rifu, some 70 kilometers to the southwest. He talked about the surprise he felt upon visiting the shopping district for the first time since last May, when he had come to the temporary facility farther inland.

“I was shocked to see what used to be the bustling heart of the town covered in these barren mounds of earth. The town’s roads aren’t even rebuilt yet. Rifu, where I live, is right next to the big city of Sendai, and it takes more than an hour to drive here. But even so, I have to say that this shopping center has plenty of food you can only get here, like all this fresh fish. If there are tasty things to be had, I expect people like me will make the trip from out of town to get them.”

In April, the Sun Sun Shopping Village will be joined by another shopping center called Minamisanriku Hamare Utatsu, located in the Utatsu district in the northeast of the town. Eight restaurants, clothing merchants, and other businesses will set up shop in this smaller center, some of them moving from the temporary shopping mall at the northern tip of Isatomae Bay.

Hopes for a Revitalized Community

Both of the new shopping centers are managed by Minamisanriku Town Future, a company set up by the town government and business owners to promote growth in the municipality. Miura Hiroaki, who serves as president of this company in addition to running Marusen, his own shop in the Sun Sun center, states clearly: “We aren’t going to survive if we stick to how we did business in the past.”

President Miura of Minamisanriku Town Future lost nine properties to the 3/11 tsunami, including his home, shops, and a factory. He is now working to rebuild his facilities one by one.

President Miura of Minamisanriku Town Future lost nine properties to the 3/11 tsunami, including his home, shops, and a factory. He is now working to rebuild his facilities one by one.

He describes what local business owners are doing to stay afloat: “Every single shop has got to come up with new ideas. Now that the new shopping centers are opening, one kimono shop switched over to the dry-cleaning business, where demand is more reliable. If we don’t try anything new we can’t expect to see any new success. Really, we’re being asked to prove our mettle as entrepreneurs.”

There are other signs of progress: town-owned permanent housing units are almost ready for residents who have been forced to live in temporary housing for years, and the harbor has regained considerable vigor, particularly in fisheries industries like oyster and wakame seaweed farming. But while Minamisanriku may be gaining two new bases for shopping activity this spring, they amount to little more than a single step forward on the commercial front. Many reconstruction projects are far from completion; the local government will not be able to move into its newly built, permanent town hall until this autumn. Minamisanriku’s population, which was already dwindling before the 2011 disaster struck, has fallen from its pre-3/11 level of 17,700 to 13,500 people today. And it is an increasingly gray-haired town: more than 30% of those residents are aged 65 or over.

Yonekura Shin’ichi, who manages the Hotel Kan’yō—Minamisanriku’s largest hotel, which served as an evacuation center following the disaster—stresses that the launch of the new shopping centers must be a springboard for further recovery in the town.

“Media interest in 3/11 has faded over time. For the first two years or so after the disaster, we did brisk business thanks to all the construction industry people, government observers, tourists, and volunteers who made their way here. Over the last three to four years, though, our vacancy rate has gone up steadily. From here on out we’ll need to plan events to publicize the local specialties people can buy and the destinations they can visit. It’s what we have to do to attract people from outside Minamisanriku, outside Miyagi, and even outside Japan.”

New Homes With No New Community

These municipal apartments in a higher area of Minamisanriku’s Shizugawa district, as well as those built elsewhere in the town, are almost all ready to house residents, but many remain in temporary housing units instead.

These municipal apartments in a higher area of Minamisanriku’s Shizugawa district, as well as those built elsewhere in the town, are almost all ready to house residents, but many remain in temporary housing units instead.

Miyakawa holds a card with messages that her neighbors gave her when she left the temporary housing unit. “We’ll never escape the sorrow of having our homes washed away, but we had each other, and that was a great source of strength.”

Miyakawa holds a card with messages that her neighbors gave her when she left the temporary housing unit. “We’ll never escape the sorrow of having our homes washed away, but we had each other, and that was a great source of strength.”

I made my way to the hilly inland district where the new housing projects are going up. These apartments are located one or two kilometers from the Sun Sun shopping center—a tough walk for the town’s elderly residents who do not drive, particularly given the steep slopes involved. There is a bus service, but the number of buses that run each day is as limited as the number of bus stops.

The 82-year-old Miyakawa Hakiko left a temporary housing facility and moved into one of these new apartments around a month ago with her son and grandchildren. “The temporary home where we lived for almost six years was cramped and inconvenient,” she admits. “But we had plenty of neighbors in the same situation. It was like the old-style nagaya ‘long house’ buildings where people were never lonely. Now I’m in this brand-new apartment, but when the rest of my family is out during the day, I’m left all alone, with nobody to talk to. If the transportation system were a bit better I’d head down to the shopping center all the time, probably.”

Minamisanriku: Under Construction

Takahashi Kazukiyo, who heads the town government’s industrial promotion division, explains the official prognosis for Minamisanriku’s recovery: “We’re positioning the new shopping centers as ‘advance models’ for a revitalized town. Ordinarily shopping facilities would come after basic infrastructure in a recovery blueprint, but we want these to serve as visible models of our recovery. Over the next year or two, we plan to complete our work on new roads, parks, roadside rest and shopping areas, transportation networks, and all the ancillary projects these will entail.”

The Minamisanriku Shizugawa Sun Sun Shopping Village has unquestionably brought fresh liveliness and hope to the community, which today is filled with the busy roar of delivery trucks and construction vehicles. Still, it is clear that true recovery in every sense—particularly emotional recovery for the residents who lost their families, friends, and homes to the destructive power of the great tsunami—will not come easily. The important task for those of us living outside communities like this one is to give thought to the reality they face today, and to keep our attention from fading with time. This is the lesson I took away from my latest visit.

The broken frame of the reinforced town hall building where many residents lost their lives in the 3/11 tsunami. The surrounding area is changing rapidly, but this structure remains as a reminder of what took place.

The broken frame of the reinforced town hall building where many residents lost their lives in the 3/11 tsunami. The surrounding area is changing rapidly, but this structure remains as a reminder of what took place.

Calm seas at the harbor in the town’s Shizugawa district. Many new buildings can be seen thanks to progress in construction of port facilities here.

Calm seas at the harbor in the town’s Shizugawa district. Many new buildings can be seen thanks to progress in construction of port facilities here.