Anime “Pilgrimages” Create New Tourist Destinations

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Shinkai Makoto’s 2016 Kimi no na wa (Your Name) was a huge anime hit in Japan, and Yamada Naoko’s Koe no katachi (A Silent Voice) and Katabuchi Sunao’s Kono sekai no katasumi ni (In This Corner of the World), both released in the same year, also performed strongly at the box office. In 2017, the first Sōdo āto onrain (Sword Art Online) theatrical release has received high praise since opening on February 18.

These film explorations of an illustrated world are having effects that spill over into the real world, too. Fan visits to locations that are the settings for their favorite anime are known as seichi junrei, or “pilgrimages.” They were such a social phenomenon in 2016 that the phrase was chosen as one of the top 10 buzzwords of the year. There are said to be some 5,000 locations to visit in all throughout Japan, of which around 700 are particularly popular.

Demand for Greater Sophistication

The pilgrimage trend has been fueled by the use of real-life scenery as a model for anime backgrounds. This in turn is a product of the increasing attention to detail in anime content and production.

Japan grew to love anime in the postwar period, but there was a time when it was mostly for children. Since around the mid-1990s, however, there have been a growing number of films and television series aimed more at an early adult audience. During the 2000s, there was a sudden spike in late-night anime for adult viewers, with more than 150 series produced each year. Viewers were growing more discerning at the same time, though, pressing creators to provide them with products that were not sloppy or rushed. Audiences demanded greater sophistication in all aspects of anime, from characters and story to direction, script, and drawing. In time, this heightened demand led to a stronger focus on realism in the works, which relied more on real-life locations drawn faithfully. Anime pilgrimages were born as viewers realized they could now visit the spots that appeared in their favorite shows.

Media Interest

Girls und Panzer materials on display outside the Ōarai chamber of commerce in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Girls und Panzer materials on display outside the Ōarai chamber of commerce in Ibaraki Prefecture.

It is hard to pin down exactly when these pilgrimages began. They first became apparent as an ongoing phenomenon of any scale when many fans visited the area around Lake Kizaki in Ōmachi, Nagano Prefecture, which had inspired the setting of the series Onegai tīchā (Please, Teacher!), broadcast in 2002. At this stage, though, fans simply made their visits and local authorities and shopping streets made no efforts to cater for them.

The media first took a serious interest when fans descended on Washinomiya Shrine in Kuki, Saitama Prefecture, and businesses seized the opportunity to profit. This time, the series in question was Raki-suta (Lucky Star), broadcast in 2007. The program attracted many people to the district and shrine. After some initial confusion in the local shopping street, stores set up a “stamp rally,” encouraging visitors to go to a list of locations to complete a set of rubber stamp imprints. They also marketed special goods tied in to the popular series.

Hida-Furukawa Station in Gifu Prefecture plays up local connections with Your Name.

Hida-Furukawa Station in Gifu Prefecture plays up local connections with Your Name.

After that the pilgrimages kept coming. Keion! (K-On!) (2009, 2010) sent fans to Toyosato in Shiga Prefecture and Sanjō-dōri in Kyoto. To aru kagaku no rērugan (A Certain Scientific Railgun) (2010, 2013) sent them to Tachikawa in Tokyo. Tamayura (2011, 2013) was a tourist boon for Takehara, Hiroshima, while Hana saku iroha (Hanasaku Iroha: Blossoms for Tomorrow) (2011) was welcome for the tourism industry in Ishikawa Prefecture. Ano hi mita hana no namae o bokutachi wa mada shiranai (Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day) (2011) has been good for Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture, and Hyōka (2012) beneficial for Takayama in Gifu Prefecture. More recently, Gāruzu ando Pantsā (Girls und Panzer) (2012, 2013) has attracted devotees to Ōarai, Ibaraki Prefecture, and Rabu Raibu! (Love Live! School Idol Project) (2013, 2014) has drawn them to Kanda Shrine in central Tokyo.

For several years, anime pilgrimages were mainly a phenomenon limited to the subculture of young enthusiasts. However, the astounding success of Your Name in 2016 changed that. It became the second most popular Japanese film ever in Japan, drawing fans even from outside traditional anime circles to locations like Hida, Gifu Prefecture, and Lake Suwa, Nagano Prefecture. This brought pilgrimages to broad public attention, and in September of the same year, publisher Kadokawa and others got together to form the Anime Tourism Association. The body is putting together a list of 88 anime “holy sites” to visit, based on Internet voting.

Fan visits can bring new life to areas suffering from depopulation. Since 2012, an increasing number of anime companies have been entering tie-ups with local authorities from the beginning of production.

A Fictional Festival Comes to Life

I would like to take a closer look at Hanasaku Iroha, as I am currently living in Ishikawa Prefecture; Hyōka, for which the local government has produced a well-received sightseeing map; and Girls und Panzer, which has apparently been most successful at attracting visitors to the associated area.

Hanasaku Iroha is an original anime series with a setting based on a former ryokan inn at Yuwaku hot springs in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture. It depicts the lives and personal growth of the granddaughter of the ryokan owner and her friends.

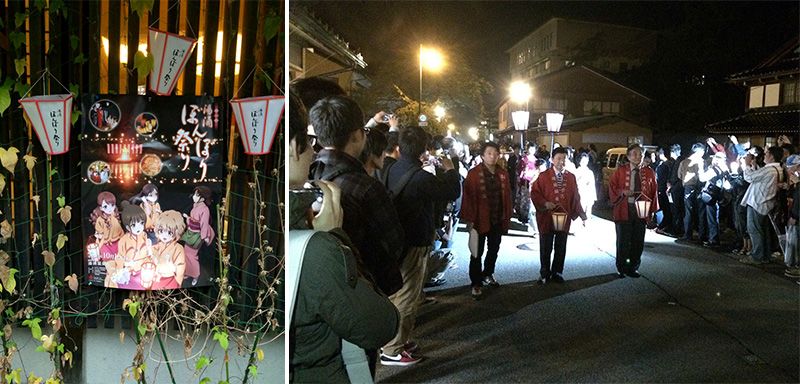

The anime features a fictional event in the hot springs district called the Bonbori Festival. In October 2011, however—the year that the series was broadcast—locals re-created the festival in real life. Since then, the event has taken place every year, with 2016 marking the sixth occasion. The plan is to make it a permanent part of the area’s tradition.

It is not the first Japanese festival to have fictional antecedents. One particularly famous example is the Meguro Sanma Festival, which derives from a rakugo story. But it is the first festival to come from an anime. Fans also make their way to Nishigishi Station in Nanao, which was the model for a location in the series. A move to decorate trains with Hanasaku Iroha characters has brought further hordes of devotees with camera in hand to what is otherwise a thoroughly typical example of Japan’s shrinking regional municipalities.

Mapping Out a Pilgrimage

Hyōka is based on a series of novels by Yonezawa Honobu in which high school students solve trivial mysteries. The stories are quite inconsequential, but the city of Takayama in Gifu Prefecture, where the author went to high school, is faithfully and beautifully described. Many fans, smitten by the anime scenery, have been inspired to make the trip. Visitors have happily snapped up copies of a “pilgrimage map” produced by the city; more than 100,000 copies have been printed to date. Walk around the streets of Takayama and you will see many young people using it for reference. There is a special corner devoted to the anime in Takayama’s Marutto Plaza, a specialty shop selling local goods. Fans also go to cafés and shrines associated with the series.

The Hyōka corner at Marutto Plaza.

The Hyōka corner at Marutto Plaza.

Girls und Panzer is set in an imaginative alternative Japan in which a form of tank battle known as senshadō, or “the way of the tank,” has become a competition. The high-school-girl heroines take part in this activity. The setting of Ōarai in Ibaraki Prefecture has benefitted from its relative proximity to Tokyo, attracting a particularly large number of visitors. Local businesses display panels with characters from the series to give fans a warm welcome. Some visitors develop a love for Ōarai itself that goes beyond their enjoyment of the anime. While in the area, many Girls und Panzer enthusiasts draw anime pictures on the wooden ema tablets at Ōarai Isosaki Shrine. Some of these display a highly professional level of ability.

Anime ema at Ōarai Isosaki Shrine.

Anime ema at Ōarai Isosaki Shrine.

Dreaming of Anime Tourists

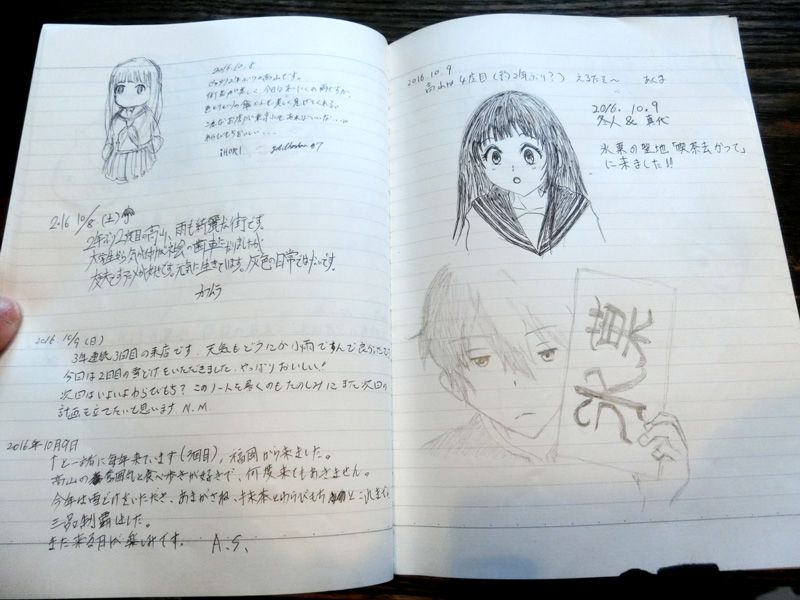

It has been estimated that more than 1 million people visit anime tourist spots each year. This figure is probably even higher, thanks to the Your Name boom. At each location, there is at least a visitor book in a café, local authority office, or station where fans can record their trip. These books reveal that visitors come from abroad as well as from Japan. Anime is popular with young people around the world. In Asia, this includes Taiwan in particular, as well as Hong Kong, South Korea, China, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. There are also comments from French, American, and other Western fans.

Even so, it is not so simple to become a pilgrimage destination. Many representatives at local authorities and shopping areas, seeing the successful revitalization an anime series can bring, dream of a similar transformation—but only a lucky few places are chosen by anime creators, and then by their fans. The producers of an anime may give their artistic urges precedence over the wishes of local businesses and governments hoping for a positive take on their areas. And even if a series showcases a vicinity as hoped for, it may not win enough followers to motivate visits. Finally, if fans are not welcomed as they would hope, they may not come back, bringing an early end to revitalization.

Diverse factors have to come together to draw in anime pilgrims. For those locations lucky enough to achieve the perfect combination, however, the tourism benefits can be extraordinary.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 6, 2017. All photographs by Sakai Tohru. Banner photo: A Hanasaku Iroha–themed train.)