Misguided Neomercantilism Threatens Japan-US Relations

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Since Donald Trump’s inauguration as president of the United States last January, it has become dismayingly clear that he actually meant a good deal of what he said during the election campaign, at least on the subject of international trade. Indeed, one of the first promises on which Trump delivered was America’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, an ambitious US-led free-trade initiative. The new administration has abandoned this multilateral approach in favor of narrowly focused one-on-one talks—and those negotiations promise to be tough. But how much does the United States really stand to gain by targeting Japan as a trade adversary?

Rash Rejection of Multilateralism

The administration’s hardline “America first” approach was on display in the recent Wall Street Journal interview of Peter Navarro, chairman of the newly established National Trade Council. In the March 8 article, Trump’s trade czar was forthright about the administration’s intent to apply the screws to its trading partners, saying, “Any country we have a significant trade deficit with needs to work with us on a product-by-product and sector-by-sector level to reduce that deficit over a specified period of time.”

Robert Lighthizer, Trump's pick for US Trade Representative, was more specific during his confirmation hearing in mid-March, singling out Japan as “a primary target . . . for increased access for agriculture.” Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross—a former banker and investor previously known for his balanced and knowledgeable perspective on Japan—has apparently felt obliged to echo Trump’s populist hard line toward China, Japan, and other countries with which the United States has chronic trade deficits.

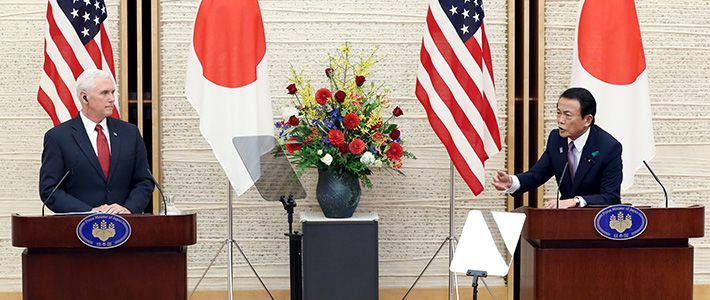

Bowing to the Trump administration’s shift in emphasis, Japan has agreed to a new bilateral forum for economic dialogue, with Vice President Mike Pence and Deputy Prime Minister Asō Tarō overseeing the negotiations. Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has said that the talks will center on the three broad topics of economic policy, cooperation on infrastructure and energy, and rules governing trade and investment. But judging from comments by Navarro and others, it will be difficult to steer the discussions away from Trump’s objective of correcting “imbalances” in specific areas, especially automotive and agricultural products.

It seems clear now that Trump means what he says about trade. But whether he is right about it is a different matter altogether. The issue is not just the pain an outcomes-based bilateral approach could cause to the countries the Trump administration has targeted. It is also whether the benefits to be extracted from such negotiations are worth the time, effort, and potential cost to Japan-US relations.

Politically Motivated Japan Bashing

The last time the United States and Japan were seriously at loggerheads over trade was some 20 years ago. In the 1980s, as the decline in US manufacturing might emerged as a major political issue, friction heated up over trade in automobiles, semiconductors, construction, beef and citrus, telecommunications equipment, and other areas. By the mid-1980s, US business and labor had united in calling for aggressive action against countries that did not “play fair,” and Japan, which accounted for a large portion of the US trade deficit, was an obvious target. Domestic political forces galvanized Washington to place intense pressure on Japan, ushering in a protracted period of Japan bashing.

Eventually, Congress took matters into its own hands by passing the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. While the law covers a great deal of ground, its most celebrated and controversial provision was Super 301, which authorized the administration to take all appropriate action against countries determined to be engaged in unfair trade practices.(*1) When the United States designated Japan a “priority country” under Super 301 in 1989, bilateral tensions intensified to the level of a trade war.

In 1990, following a recommendation from US Trade Representative Carla Hills, President George Bush dropped Japan from the list of Super 301 priority countries, citing progress in trade talks. The decision drew angry criticism from members of Congress. Trade hawks responded with bitter complaints that the executive was overruling the will of Congress and that the omission of Japan from the list of priority countries made a mockery of a provision that had been drafted specifically with Japan in mind. It was a pivotal episode that revealed to Japanese officials what a politically potent issue Japan-US trade had become.

Bilateral trade negotiations between Japan and the United States continued concurrently with the protracted Uruguay Round (1986–94) of the multilateral General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. By the mid-1990s, bilateral agreements had been reached in several key product areas, the World Trade Organization had been established, and the focus of Washington’s strategy shifted. Later, growing impatient with the slow progress of WTO negotiations, the United States spearheaded the Trans-Pacific Partnership as a sweeping regional framework capable of accelerating global progress in free trade and investment, including protection of property rights. Now Washington has abruptly abandoned the TPP and reverted to the old strategy of bilateral negotiations with countries having the temerity to export more merchandise to the United States than they import from it. This might be a good time to review and reassess that strategy.

Chronology of Japan-US Trade Relations

| 1970–72 | Japan-US textile negotiations trigger first outbreak of bilateral trade friction in the postwar era |

| 1973– 79 | GATT Tokyo Round |

| 1981–84 | Japan adopts voluntary quotas on auto exports to US |

| 1983–88 | Japan-US Yen-Dollar Committee |

| 1985–86 | MOSS (market-oriented sector selective) talks |

| 1985 | US semiconductor industry files Section 301 petition with USTR concerning market barriers in Japan |

| Plaza Accord on currency market intervention to strengthen yen | |

| 1986–94 | GATT Uruguay Round |

| 1988 | Japan, US reach agreement on beef and citrus |

| Japan, US reach construction agreement | |

| 1989 | Japan, US reach agreement on telecommunications equipment |

| 1989–90 | Japan-US Structural Impediments Initiative |

| Japan-US Super 301 trade talks | |

| 1993–98 | Japan-US Framework Talks |

| 1995 | Establishment of World Trade Organization |

| 1996 | Japan, US reach semiconductor agreement |

| 1997–2001 | Japan-US deregulation dialogues |

| 2015 | 12 countries, including US and Japan, reach broad agreement on TPP |

| 2017 | US announces withdrawal from TPP |

| Japan-US Economic Dialogue launched |

American Righteous Indignation

What, then, did the Japan-US trade talks of the 1980s and 1990s accomplish for the United States and for Japan?

One comparatively productive series of talks held during this time was the Structural Impediments Initiative (1989–90). Unlike the sector- and product-specific negotiations of the period, these talks focused for the first time on identifying and solving structural problems underlying the Japan-US trade imbalance, including long-term business relationships within Japan’s keiretsu corporate groups and other non-tariff trade barriers built into the Japanese business environment.

The SII led to significant relaxation of the regulations governing the establishment of large-scale retail businesses and the strengthening of the Anti-Monopoly Act and Japan Fair Trade Commission. The liberalization of Japan’s retail sector, leading to the spread of big-box stores like Toys R Us, was probably a welcome development from the viewpoint of the Japanese consumer, although it doubtless had its negative impacts as well.

Focusing on benefits to the average Japanese consumer, Washington presented the trade negotiations as a campaign for all that is good and just. Of course, Washington’s aim was quite simply boosting US industry in the face of global competition. But its attitude, all too frequently, was that of a morally superior entity crusading for truth, justice, and the American way. Indeed, this might be cited as an enduring feature of the American style of negotiation. Another prominent feature is the tendency to approach trade with the view that one side must emerge as the winner and the other the loser. The office of the US Trade Representative, responsible for conducting bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations, is located in the Winder Building, an unassuming, five-story building just west of the White House. But the agency’s modest physical size is belied by its army of shrewd, seasoned lawyers. When negotiations gather steam, the talks tend to assume the tone of a historic court battle.

Faced with a wall of self-righteous intransigence, the Japanese side tends to grow increasingly frustrated. To be fair, one should point out that Japanese negotiators and their American counterparts often develop close personal ties that endure long after the negotiations are over; I imagine there is a special bond that develops between people who have weathered such an intense ordeal together. But among the politicians and bureaucrats who operate at a remove from the actual negotiations, the process always seemed to breed anti-American rancor. The same tendency was seen among ordinary Japanese citizens, who heard about the talks via the news media. There is no question that the Japan-US trade talks of the 1980s and 1990s fostered widespread anti-American sentiment that persists to this day.

Shortsighted Take on Trade

In the end, both Japan and the United States paid a heavy price for the agreements they reached on various products and structural impediments. The big question is whether those agreements corrected the trade imbalance between our countries. And the answer is clearly no. Whatever effect they had on overall trade volumes was extremely limited. The basic reason is that the bulk of the imbalance grew out of macroeconomic factors rather than unfair trade practices.

The other issue is that, since trade is by nature multilateral, dealing with it in a narrow bilateral framework means ignoring the bigger picture. True, in 2016, Japan had a ¥10 trillion trade surplus with the United States, but it posted a deficit with many other trading partners, including China, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Australia, France, and Italy, not to mention the oil-producing countries of the Middle East.

The Trump administration’s narrow focus on trade in goods is another example of shortsighted and outmoded thinking. In the past, Japan’s chronic surpluses in merchandise were accompanied by a huge deficit in the broad area of services, including shipping, tourism, intellectual property rights, and telecommunications. But where goods are concerned, Japan’s trade balance plummeted after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 and only shifted back into the black in 2016. Meanwhile, its services deficit has been shrinking. More important, the primary income account—representing income from foreign investments, including profits generated by overseas production facilities and interest and dividends from foreign stocks and bonds—has become the most reliable generator of surpluses in Japan’s international balance of payments. In 2016, Japan’s primary income account surplus was ¥18.1 trillion, more than three times its ¥5.6 trillion merchandise surplus.

Trends in Japan’s International Balance of Payments

(trillion yen)

| Current account | Goods | Services | Primary income | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | 11.9 | 12.9 | (2.2) | 1.6 |

| 1990 | 6.4 | 10.0 | (6.1) | 3.2 |

| 2000 | 14.0 | 12.6 | (5.2) | 7.6 |

| 2005 | 18.7 | 11.7 | (4.0) | 11.8 |

| 2007 | 24.9 | 14.1 | (4.3) | 16.4 |

| 2009 | 13.5 | 5.3 | (3.2) | 12.6 |

| 2012 | 4.7 | (4.2) | (3.8) | 13.9 |

| 2013 | 4.4 | (8.7) | (3.4) | 17.6 |

| 2014 | 3.9 | (10.4) | (3.0) | 19.4 |

| 2015 | 16.2 | (0.8) | (1.9) | 21.0 |

| 2016 | 20.3 | 5.5 | (1.1) | 18.1 |

Source: Ministry of Finance balance of payment statistics.

To be sure, the United States posted a mammoth trade deficit with respect to goods during the same period, a full $750.1 billion (roughly ¥80 trillion). But its services surplus of $247.8 (about ¥27 trillion) was the world’s highest, and its primary income balance was $180.6 trillion (about ¥20 trillion).

Red Meat for the Masses

Any bid to forcibly equalize the balance of trade between two countries is predicated on a gross oversimplification of the dynamics of international trade and investment. Moreover, most US trade officials are fully aware of this, according to knowledgeable sources in the Japanese government. That being the case, one would think it possible to avert another trade conflagration through rational discussion among the parties concerned.

Unfortunately, the present situation offers scant grounds for optimism on that score. As in the 1980s, Japan bashing is a convenient source of political red meat. The concept of American jobs lost to an unfair and adversarial trade partner is easy to grasp and quick to take hold. The notion that Japan is flooding the United States with exports while deliberately shutting out imports plays well with voters angry over the loss of good American jobs—especially those in the deindustrialized Rust Belt of the American Midwest. And it is well known that Donald Trump won the presidency largely by appealing to those voters’ frustration and malaise.

Thanks to the electoral triumph of Trump-style populism, an unsavory episode in postwar history seems poised to repeat itself. Once again, people who should know better are entering into a futile campaign to correct macroeconomically rooted trade imbalances via tough talk at the bilateral level. We have already seen what an impact such a crusade can have on bilateral relations, and today the stakes for the region are higher than ever. Trump’s heedless neomercantilism is fraught with danger.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 21, 2017. Banner photo: Deputy Prime Minister Asō Tarō and US Vice President Mike Pence during a joint press conference at the prime ministers official residence in Tokyo on April 18, 2017, following the start of a new bilateral economic dialogue. © Jiji.)(*1) ^ Section 301, originally part of the US Trade Act of 1974, was strengthened by means of an amendment incorporated into the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. “Super 301,” as the beefed-up provision was known, required the USTR to issue a report on US trade priorities, prepare a list of priority countries that practiced unfair trade, investigate and negotiate with any country thus identified, and impose sanctions if necessary. Japan’s citation as an unfair trader in 1989 set in motion negotiations that led to Japanese concessions in the areas of supercomputers, communications satellites, and forestry products. Super 301 expired in 1991, though it was temporarily reinstated several times in the mid- and late 1990s.—Ed.