Even as Evacuation Orders are Lifted, Recovery Remains Distant Prospect for Many Fukushima Residents

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Beginning of the End, or the Prelude to New Heartache?

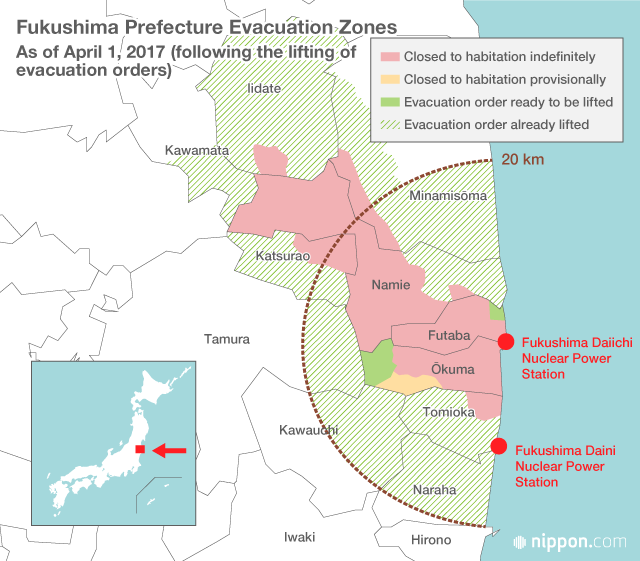

The Japanese government on March 31 and April 1 of this year lifted evacuation orders for areas around the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station it issued in the wake of the nuclear accident at the plant more than six years ago. The decision finally allowed some 32,000 residents of the four radiation-affected municipalities of Iidate, Kawamata, Namie, and Tomioka to return to their homes. Following the move, the only places still subject to evacuation orders are Futaba and Ōkuma (where the Daiichi plant is located) and parts of five neighboring towns and villages.

The Japanese media almost universally hailed the decision as a “major milestone” toward residents of affected areas rebuilding their lives. But this supposed milestone can be taken in two quite different ways. In much of the media there was an optimistic sense of a return to normalcy, resulting in the view that the evacuation orders lifting was a long-awaited new beginning in the recovery effort, and that residents would finally be able to start rebuilding their lives and communities. Another, more cynical view, however, is that it merely marked the start of new string of woes. Considering the challenges that face residents, in my opinion this second interpretation is closer to the truth.

The optimistic view is pushed by the national and prefectural authorities in charge of advancing recovery efforts in Fukushima, and is based on the following scenario.

- Designate evacuation zones across areas affected by radiation, and provide support to evacuees in the form of temporary housing and compensation.

- Decontaminate the affected areas.

- Prepare to lift the evacuation orders as radiation levels fall.

- Rebuild local infrastructure and reestablish local services, rebuilding health, welfare, and retail facilities where necessary.

- Lift evacuation orders.

- Evacuees return home.

For the thousands of evacuees forced to live away from their homes over the past six years, however, there is quite a different sense to the orders being lifted. Some people will decide to return home while others will remain where they are. No matter their decision, though, we must face the fact that new challenges await both groups.

Many of those most eager to return home are the elderly, but health and welfare provisions are still far from satisfactory in many areas. There are also lingering doubts for other members of the community, such as the future of the area’s farming, forestry, and fisheries. Local economies have been devastated, raising the question of employment and whether people will even be able to buy daily necessities, let alone support themselves long term.

The situation at the power plant also remains precarious and much work remains to be done. The problem of radioactive water has yet to be solved and a medium-term storage facility must be found for huge amounts of contaminated material. However, there is not even a timetable for when these will be accomplished. Faced with such uncertainty, many people will simply choose to remain where they are rather than risk returning home. However, this decision brings a different set of problems, as many of the support systems put in place to help evacuees will be cut off now that they are no longer prevented from going back.

In surveys carried out between 2014 and 2017 by the Reconstruction Ministry, the Fukushima Prefectural government, and the evacuated municipalities, more than half of residents of Futaba, Namie, Ōkuma, and Tomioka said they did not plan to return to their homes after the evacuation orders were lifted. In other areas where more than a year has already passed since evacuation orders were rescinded, the number of residents who have returned remains at 20% or less everywhere except Tamura. These sobering figures illustrate the steep road awaiting evacuees wishing to go home.

Assessing Conditions in the Affected Areas

The fact that authorities lifted evacuation orders despite so many issues still unresolved demonstrates a disregard for the challenges confronting residents. Now more than ever, we must consider and assess the uncertainties residents face and ascertain future challenges.

In the areas recently deemed fit again for human habitation, flexible containers filled with contaminated materials still lie in heaps at various temporary storage points, where they have been since clean-up operations began. While the plan is to eventually move these to medium-term storage facilities, I wonder if authorities when deciding to lift the evacuation order really understood the anxiety and stress placed on residents who must live their lives surrounded by mountains of contaminated debris.

Containers of contaminated soil in temporary storage await safety checks in Minamisōma, Fukushima, on June 11, 2016. Photo by Tsuchie Hironori. (© Manichi Shimbun/Aflo)

Containers of contaminated soil in temporary storage await safety checks in Minamisōma, Fukushima, on June 11, 2016. Photo by Tsuchie Hironori. (© Manichi Shimbun/Aflo)

The town of Hirono is situated 22 kilometers from Fukushima Daiichi. Following the disaster, the town’s medical services fell to the sole efforts of the head of the local hospital, Dr. Takano Hideo. However, the future of the hospital was thrown in doubt when Takano died in a fire late last year. Nakayama Yūjiro, a physician in Tokyo, assisted for a time, spending two months earlier this year as the hospital’s resident doctor.

Nakayama wrote a diary based on his experience, which was published in April 2017 by Nikkei Business online as Ishi ga mita Fukushima no riaru (The Reality of Fukushima: A Doctor’s View). In his account, Nakayama describes the ongoing tragedy of the disaster and discusses the numerous people who have died from conditions brought on by the stress of residing in temporary living conditions. He points to three main reasons for these deaths: Separation from family and loss of community; interruption of ongoing medical treatment; and change of environment. Nakayama’s experience illustrates how in indirect ways, the death toll from the disaster continues to rise.

Giving Up on the Dream of Going Home

Sasaki Yasuko’s memoir of her years in temporary housing.

Sasaki Yasuko’s memoir of her years in temporary housing.

The situation is worse still for people whose homes are subject to ongoing evacuation orders. Sasaki Yasuko, who was evacuated from her home in Namie, spent the time since the disaster in temporary housing in the town of Koori. In a 90-page record of her life as an evacuee called Osoroshii hōshanō no sora no shita (Under a Fearsome Radioactive Sky), she writes: “I don’t want to die in temporary housing. That’s all I ask. Everyone is talking about wrapping things up and bringing an end to the disaster—but I don’t want my life to end like this. . . . Since the disaster, there seem to be slogans everywhere I go that are meant to keep our spirits up. But what more can I do than what I’m already doing? I wish someone would tell me what I’m expected to do.”

I met Sasaki for the last time in the spring of 2013. She was still living in temporary housing and was working to complete a model of her home in Namie, desperately trying to recreate from memories a place she thought she would never see again. Around a month after that, I learned that she had been hospitalized and had passed away at the age of 84. I also heard that before entering the hospital, she had taken her model and smashed it to pieces.

Sasaki Yasuko toward the end of her life, at work on a model of her abandoned home in Namie. Photo taken by the author in 2013.

Sasaki Yasuko toward the end of her life, at work on a model of her abandoned home in Namie. Photo taken by the author in 2013.

I had many other opportunities to talk to people whose homes are in areas “closed to habitation indefinitely.” Several of them told me that when they had tried to tidy up one of their short visits home, they found their houses in a state of chaos as a result of intrusions by boars and other wild animals. The residents asked the authorities to do something about it, saying, “Can’t you catch the boars, or at least hire someone to stop them from getting into our houses?” But no business could be persuaded to take the project on as everyone was too afraid of the high radiation levels.

Faced with difficulties and indignities like this, people’s eagerness to return home slowly withered. They say that the radiation tore everything up by the roots—history, culture, community—and they wonder if any amount of compensation can make up for such a loss. Robbed of their local heritage, many residents of affected areas continue to lament the cultural implications of the disaster.

The Need to Support Both Returnees and Evacuees

The authorities imagine a simplistic scenario where lifting the evacuation orders results in everyone returning home and living happily ever after. But life is not so simple, and this storyline does not include solutions for problems like those outlined above. As well as working to restore and rebuild the physical infrastructure in the evacuated towns and villages, the authorities need to work with residents to develop programs that will help them get their lives back on track. These programs need to have realistic outlooks of the future and must consider the hopes of the residents themselves.

From the initial days after the disaster, the message from the national government and Tokyo Electric Power Company, the operator of the Daiichi plant, has been: “Leave this to us.” This has permeated their attitude in establishing support efforts for evacuees in temporary housing, setting radiation safety standards, cleanup work, compensation negotiations, livelihood support, and reconstruction plans. Everything has been handled in an ad hoc fashion, leading to misunderstanding and anxiety and opening gaps between the authorities and those they are supposedly trying to help. For residents, all these actions are closely connected. There is still no process for building consensus and bridging the gulf that has formed between the authorities and the residents who should be playing a leading role in rebuilding their communities. It is in this context that the evacuation orders were lifted.

The authorities should make it a priority to draw up a less simplistic scenario that better reflects the reality on the ground. There must be a multiple-track plan balancing programs to rebuild communities and support returnees’ lives back home with measures that provide help to evacuees who choose to remain where they are. One idea worth considering would be a program that allowed evacuees to divide their lives between two areas for a bridging period, giving them time to rebuild their hometowns while remaining in temporary housing. One way this could be accomplished is to provide residences where evacuees could live on a part-time basis as they work to rebuild their communities and repair their damaged and neglected homes.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 9, 2017. Banner photo: A photographer snaps photos of somei-yoshino cherries in Tomioka, Fukushima Prefecture, on April 12, 2017. Most of the 2.2-kilometer stretch of cherry trees is barricaded off inside an evacuation area. Since this spring, the first 300 meters of the road have been opened to the public during the daytime. The district is now designated an “area closed to habitation provisionally.” © Jiji.)Great East Japan Earthquake Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station nuclear power Fukushima TEPCO