Seeking an Exit Strategy from the Bank of Japan’s Extreme Monetary Easing

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Massive Holdings of Japanese Government Bonds

In April 2014, the Bank of Japan eased its monetary policy and began to purchase massive quantities of Japanese government bonds. Through this policy of quantitative and qualitative easing (QQE),1(*1) JGBs held on the BOJ’s balance sheet rose to ¥420 trillion (of which ¥390 trillion are long-term JGBs), or more than 40% of JGBs outstanding. In comparison, the Federal Reserve Board holds 12% of US Treasuries outstanding. Few other central banks have as many government bonds on their balance sheets as Japan’s does.

The BOJ has established a policy target of 2% for the growth rate of the consumer price index. Once this target is achieved, it will begin to unwind its extreme quantitative easing. If this is accompanied by the gradual rise of interest rates, turmoil in markets will be limited. Concerns, however, are growing among market participants that the long-term interest rate will rise sharply. The shock of a sudden increase in interest rates will hit the earnings of financial institutions. Hence, there are mounting calls for the Bank of Japan to disclose specific simulations of its exit from monetary easing so markets can anticipate the trend for interest rates.

Negative Interest Rate Hits Bank Earnings

The April publication of a document on the BOJ’s monetary policies by the Administrative Reform Promotion Headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party prompted the current apprehension over BOJ exit strategies. The document raised such issues as whether the insolvent state of the BOJ with its massive holdings of JGBs would lead to a loss of confidence in the yen and in Japan as a whole, whether the earnings of financial institutions would be squeezed from the increase of the interest rate for reserve deposits when exiting from monetary easing, and whether the soundness of government finances would be harmed by the sharp rise of interest rates for JGBs. These issues are currently being discussed from a range of perspectives.

Another issue facing the BOJ is the growing difficulty of purchasing ¥80 trillion in JGBs annually (the current level of purchases is around ¥60 trillion). This figure already exceeds the annual government issue of the bonds. As a result, the BOJ is only able to achieve its purchase target by acquiring JGBs on the secondary market with a negative interest rate (over par issue).

Naturally, the BOJ will record a loss when JGBs purchased with a negative interest rate are redeemed. Whether this is a sustainable policy is highly doubtful. Since current policy will clearly need to be terminated at some point in time, the demands of market participants for clarity about exit procedures and for the disclosure of exit simulations are extremely reasonable.

The ill effects of QQE are spreading. A zero or negative interest rate policy pursued over the long term has reduced the lending spreads of financial institutions and is suppressing their earnings. Banks’ diminished risk buffers are curtailing their capacity to extend new loans.

Since the BOJ’s intervention has removed so many JGBs from the secondary market, daily trading has contracted, and the long-term interest rate is fading in the Japanese market as a useful indicator. While JGBs are seen as having unparalleled creditworthiness, their interest rate is no longer serving as a reliable indicator. Without an indicator for long-term interest, there will be no basis for fixing the interest rate for corporate bonds. The same can be said for the interest rate for housing loans. Such a situation will unsettle the finances of companies, and financial institutions will be reluctant to make long-term loans.

The Broken Promise of Short-Term QQE

QQE was intended to be a short-term monetary policy that would last for two years. However, major changes in the economic environment, such as the decline of crude oil prices, compelled the BOJ to keep this policy in place for a longer period. Now that more than four years have passed, CPI is trending near zero despite the BOJ’s policy target of 2% inflation. As long as the BOJ holds to its 2% target, it will likely maintain its QQE policy.

Now is the time to carefully consider whether 2% should be an absolute target. While this level of inflation has not been achieved, a weaker yen and higher share prices, which were the initial covert targets of QQE, have been realized (BOJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko was able to persuade foreign central banks that QQE was a domestic monetary policy and not a foreign exchange policy).

Abenomics also won acclaim for achieving a weaker yen and higher share prices rather than attaining a 2% increase in CPI. Since prospects for a deflationary economic spiral have waned, the downward revision of the CPI target should be considered in monetary policy.

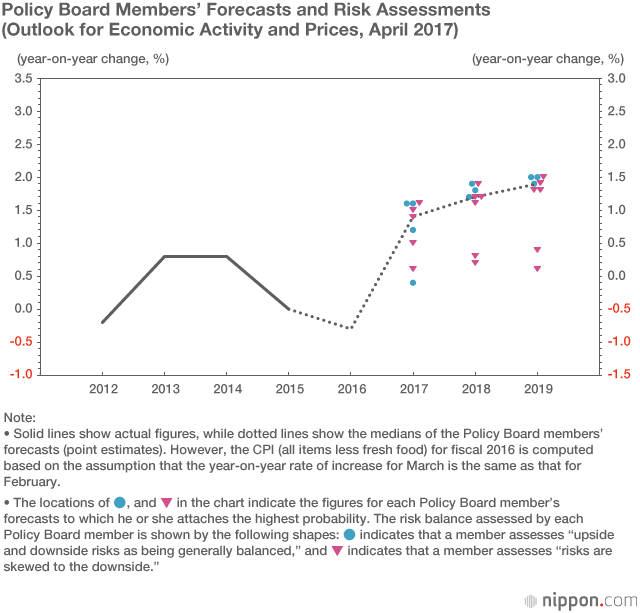

In the April Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices, the BOJ states, “The timing of the year-on-year rate of change in the CPI reaching around 2 percent will likely be around the middle of the projection period—that is, around fiscal 2018. Thereafter, the rate of change is expected to remain at around 2 percent.” The inflation forecasts of Policy Board members are also on the high side, with the median being 1.7% for fiscal 2018 and 1.9% for fiscal 2019.

As depicted in the chart, the slope of the graph has become far less steep in 2017, and its current shape can no longer be called realistic in relation to the policy target. The BOJ has revised its CPI outlook five times since instituting QQE. Can there still be anyone who believes in this outlook?

As depicted in the chart, the slope of the graph has become far less steep in 2017, and its current shape can no longer be called realistic in relation to the policy target. The BOJ has revised its CPI outlook five times since instituting QQE. Can there still be anyone who believes in this outlook?

(*1) ^ To supplement the limits of monetary policy, the BOJ instituted a negative interest rate policy in January 2016. Then, in September 2016, it began Yield Curve Control where the interest rate for 10-year JGBs is held to 0%.

Lowering the 2% Inflation Target

It is highly probable that CPI will rise by 1.0% or better in 2018 from the improvement of the supply-demand gap (demand will exceed supply with respect to the operation of labor and capital investments) and from the increase of wages for non-regular workers. Once this occurs, the BOJ can reduce its CPI target or claim that 1.0% or better is close enough to 2% and announce that conditions are in place for exiting monetary easing.

The conventional approach when the policy target is achieved would be to first slow the pace of JGB purchases (tapering), before halting the purchase of JGBs and reducing the size of banks’ current accounts with the BOJ to the reserve requirement. The BOJ can sell the JGBs on its balance sheet or wait for them to reach maturity. The textbook approach to interest rate policy would be to reverse the zero interest rate (a negative interest rate for some current account deposits) and to raise interest rates to normal levels.

Given its task of controlling the financial market, the BOJ will find it difficult to reduce or maintain the level of JGBs accumulated through QQE in implementing the exit process. Should JGBs be sold, the long-term interest rate will rise. If this interest rate climbs above the 2% target for CPI, the BOJ will be forced to curb the sale of JGBs. Fiscal policies will also be affected. Since the interest rate for new or refinancing JGBs will also rise, the government will need to increase the issue of JGBs to meet interest payments. As a result, the cost of servicing JGBs will gradually increase.

Should the issue of JGBs grow, this will place further upward pressure on interest rates. When this occurs, the BOJ will be compelled to curtail the sale of JGBs. Depending on the situation, it may even have to expand the purchase of JGBs. The BOJ cannot simply sell JGBs while ignoring its impact on the market. Having acquired so many JGBs, the movements of the BOJ have become as restricted as a whale trapped in a pond.

Controlling Long-Term Interest Rate Is Key

What sort of exit strategy is possible in the face of such restrictions? My interviews of economists, former BOJ staff, and others knowledgeable about monetary policy all indicated an exit strategy based on controlling the long-term interest rate. Currently, the BOJ is holding the interest rate for 10-year JGBs to 0% through a policy of yield curve control. What the BOJ should do is maintain this policy while tapering the purchase of JGBs without determining an annual target for JGB sales.

Now that quantitative easing’s lack of effect on CPI has been verified and its theoretical failure has become widely known, the BOJ should abandon its current monetary policy with an ambiguous monetary base target and return to an interest rate policy where the long-term interest rate is made the policy target.

The control of the short-term interest rate should be subordinated to the control of the long-term interest rate and left to the market as with the monetary base. In addition, the BOJ should allow the yield curve to steepen significantly or to even invert. Also, when the 10-year JGB no longer functions as a market indicator, the BOJ should use as its target for monetary policy the five-year JGB or JGBs with maturities longer than 10 years. The point is to view the shape of the yield curve flexibly rather than as being fixed as is the case in the current policy of yield curve control.

This proposal is derived from the strong linkage between the foreign exchange market and the long-term interest rate. A widely shared belief of market participants is that the foreign exchange market will react when the spread between the long-term interest rates of Japan and the United States widens to 2% or more. The proposed monetary policy can be expected to stabilize the foreign exchange market with a direct impact on Japan’s economy and society.

A Return to Sound Government Finances

It is safe to assume that the BOJ is fully engaged in developing exit scenarios. Only the BOJ with exclusive authority over monetary policy can respond to market imbalances and volatility. This fact should be sincerely accepted by government, in particular by the Prime Minister’s Office, which cannot move markets whatever it decides to do. The same can be said for the Ministry of Finance. There are no market players who deal in stocks, foreign exchange, and long- and short-term interest rates at the same time. Only the BOJ is able to do so.

The excess liabilities of the BOJ deserve some comment. When the BOJ and the Japanese government are viewed together as unified government, this becomes an issue of whether profit and loss are assigned to the former or the latter. Either way, this will not influence monetary policy. However, should the issuance of JGBs expand further, their creditworthiness is certain to be affected.

Since excess savings theoretically correspond to a current account surplus, as long as Japan maintains a current account surplus—in other words, as long as savings, the source of funds for digesting JGBs, remain in excess—creditworthiness will not materialize as an issue. However, as Japan’s society ages and its birthrate declines, savings can be expected to be drawn down in the future. Whether steps can be taken toward restoring sound government finances before savings decrease in earnest deserves to be made a fiscal policy issue. This is why Governor Kuroda stressed when instituting QQE that it was conditioned by a return to sound government finances.

Prepare for Risk of Weaker Yen

With regard to the excess liabilities of the BOJ, there is the view that, since the BOJ’s holdings of exchange-traded funds have increased and since their unrealized gains have grown, the BOJ can use such gains to offset the losses incurred from selling JGBs. It should not be forgotten, however, that such gains are influenced by the fluctuations of the stock market. The unrealized gains of ETFs are an issue that should be detached from exit strategies.

In fiscal 2016, the BOJ did record gains on the order of hundreds of billions of yen on the sale of stocks it had previously bought from financial institutions. These were stocks that were acquired when the stock market was down. The ETFs purchased through QQE, however, have a relatively high book value. It would be overly optimistic to think that all these ETFs can be sold at a profit when the time comes to sell. Since it will place downward pressure on the stock market, the sale of ETFs will not be readily accepted by the Prime Minister’s Office. Hence, the sale of the BOJ’s ETF holdings should be considered a political issue separate from monetary policy.

I have stated above that the BOJ may adopt a more flexible CPI target in 2018. This prospect is related to the term of Governor Kuroda expiring next spring. The heads of the central banks of Japan, the US, and Europe have tended to wind up their monetary policies when their terms reach an end. This displays courtesy to their successors by not passing on the responsibility for current policy. It is my hope that Governor Kuroda will act in this manner.

At a press conference following the June Policy Board meeting, Governor Kuroda maintained his opposition to releasing exit simulations, stating that it would not be appropriate to disclose specific simulations of exit strategies since it would only create confusion. There can be no denying, however, that some form of communication with the market is necessary.

The Federal Reserve Board has already exited from monetary easing, and the European Central Bank has begun to explore exit strategies. If Japan alone does not disclose exit strategies when others have done so, the yen has the potential of depreciating beyond the expectations of the BOJ and the Japanese government. This is depreciation that would impart a negative blow to Japan’s economy by overshooting the level that boosts corporate earnings and lifts share prices. Given this prospect, now is the time to consider the possibility of an economic shock triggered by the depreciation of the yen.

On July 20, 2017, the Bank of Japan pushed back the expected timing for achieving its 2% inflation target to around fiscal 2019. This is the sixth delay made to this target.—Ed.

(Originally published in Japanese on July 10, 2017. Banner photo: BOJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko at a press conference following a Policy Board meeting on June 16, 2017, at the Bank of Japan Head Office in Tokyo. © Jiji.)