The Meaning of Midwinter

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

From December 2, 2011, to February 14, 2012, Atelier Muji—an art space in Tokyo’s Yūrakuchō district operated by the retailer Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd., which runs the Muji branded shops—joined the Tama Art University Institute for Art Anthropology to present the Winter Solstice Festival. The event was an invitation to reflect on the meaning of the winter solstice, and was arranged in three phases, focused on the themes of “bind,” “circle,” and “connect.”

A Festival to Welcome the New Year

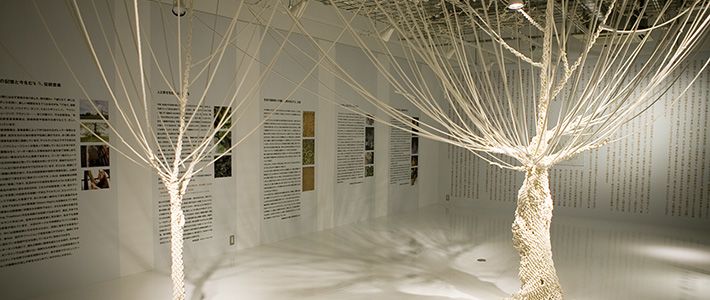

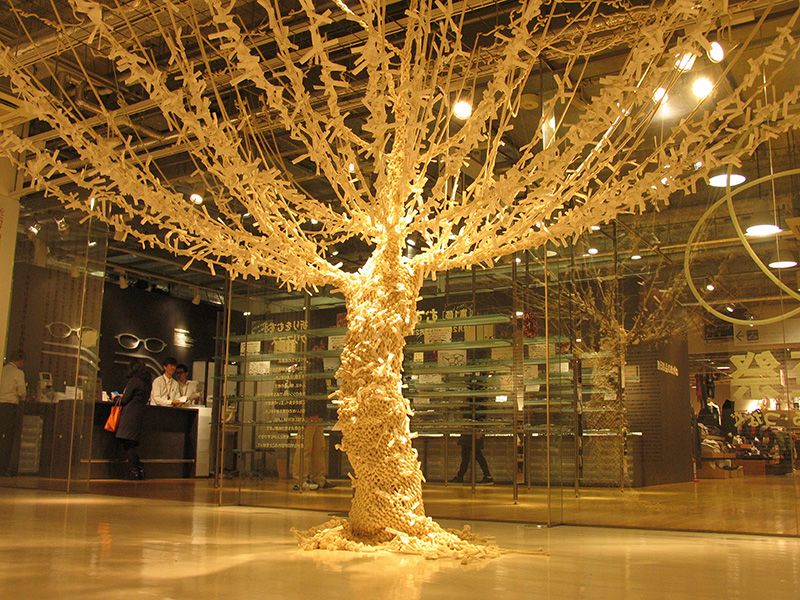

The first phase of the event explored the role played by the winter solstice in the origins of so many festivals held in the last days of the year, including Christmas. Two trees knitted from white rope filled the exhibition space. The knitted rope roots came together to form trunks and branches reaching the ceiling. The work’s creator, Sanada Takehiko, has shown installations made from clothing and textiles in and outside of Japan.

Winter solstice festivals date much further back into European history than even the earliest Christmas celebrations. Sanada adopted Celtic symbolism for these winter solstice pieces. Celtic culture in particular revered the holly plant as sacred. Visitors to the exhibit were asked to write down their hopes or prayers on small sheets of paper, and to tie the papers to the branches of the rope trees. Sanada’s hope was that visitors would play a part in making the trees thrive over the course of the event—binding their wishes to the trees and binding themselves to the exhibit in the process.

Institute for Art Anthropology professor and scholar of Celtic culture Tsuruoka Mayumi explains: “The earth is lit by sunlight for a shorter time on the winter solstice than on any other day. It also signals the approach of spring, and with it, the emergence of new life. Ancient peoples were deeply conscious of this phenomenon and understood the winter solstice as the one day that ‘binds’ each old year with the new. Celts in particular held winter solstice festivities to celebrate the rebirth of life and nature. In the darkest days of winter, Celts celebrated by decorating evergreen holly trees, a symbol of life, holding feasts, and praying for bountiful harvests in the new year.”

Tsuruoka notes connections with her own culture. “Japan has a remarkably similar new year’s tradition of placing pine branches at the gates to a home, or decorating the home’s interior with the native Japanese plants nanten [Nandina domestica] or senryo [Sarcandra glabra], both evergreen and dotted with red berries. Even such far-flung countries and cultures are still likely to share a similar understanding of the bond between humans and nature.”

Tsuruoka notes connections with her own culture. “Japan has a remarkably similar new year’s tradition of placing pine branches at the gates to a home, or decorating the home’s interior with the native Japanese plants nanten [Nandina domestica] or senryo [Sarcandra glabra], both evergreen and dotted with red berries. Even such far-flung countries and cultures are still likely to share a similar understanding of the bond between humans and nature.”

Tsuruoka touches on another form of binding brought to mind by the event. “Since March 11, many people in Japan have been reconsidering their priorities in life. My hope is that this event will help people feel more strongly the bond between humanity and nature that is so often forgotten in today’s world.”

The second phase of the exhibit ran from December 27 to January 10 to see off the old year and welcome the new—marking the circle formed by the cyclical passage of years. The third and final phase of the exhibit, running from January 12 to February 14, was a consideration of the connection between the winter solstice and the practice of welcoming the coming spring.

Winter Solstice Atelier Muji Tama Art University IAA Institute for Art Anthropology Sanada Takehiko Tsuruoka Mayumi Holly Celtic Culture Christmas