Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

Araki Nobuyoshi: An Artistic Rebel, Unbowed

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

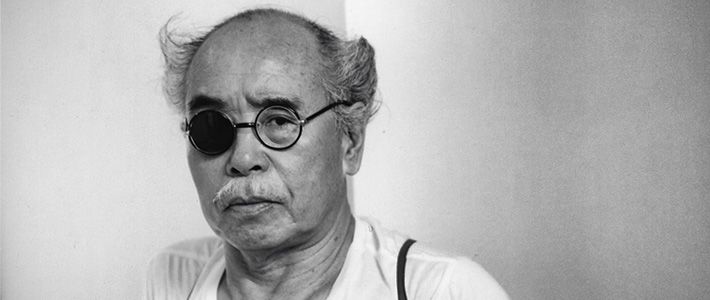

Araki Nobuyoshi is one of Japan’s best-known and most popular photographers. Now in his seventies, he shows undiminished energy, continuing to exhibit at art museums and galleries at home and abroad. He also has more than 500 publications to his credit.

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print. (© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print. (© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)

Eros and Thanatos

Araki was born in 1940 in Shitaya (now Taitō), in the heart of Tokyo’s shitamachi “low town” of small commercial establishments and residences. The family business was making wooden geta clogs, but Araki’s father Chōtarō was also an avid amateur photographer. Under his father’s tutelage, Araki began taking photographs himself while still in elementary school.

The Araki house stood directly opposite Jōkanji temple. This was known as a nagekomi-dera (throw-in temple) because during the Edo period (1603–1868) the bodies of prostitutes from the Yoshiwara courtesan district with no family to claim them had been dumped in the temple grounds. It became Araki’s childhood playground. In later years, he would dub the basis of his photography “Erotos.” The word is a classic Araki concoction, combining the Eros of sex and life with Thanatos, the embodiment of death. We could even say that the essence of Araki’s talent, slipping effortlessly between the worlds of the living and the dead, lies rooted in the soil where he was born and grew up.

By high school Araki had already decided he would be a photographer. In 1959 he entered Chiba University in the Department of Photography and Printing Engineering. Most of his courses were science classes and he struggled hard for every credit, but was finally able to graduate in 1963 and joined Dentsu, Japan’s leading advertising agency. His graduation project was the photo album Satchin, in which he vividly captured the lives of a gang of children in his neighborhood. In 1964 the work won the first Taiyō Prize for photo reportage sponsored by the pictorial magazine Taiyō. This prize marked Araki’s public debut as a photographer.

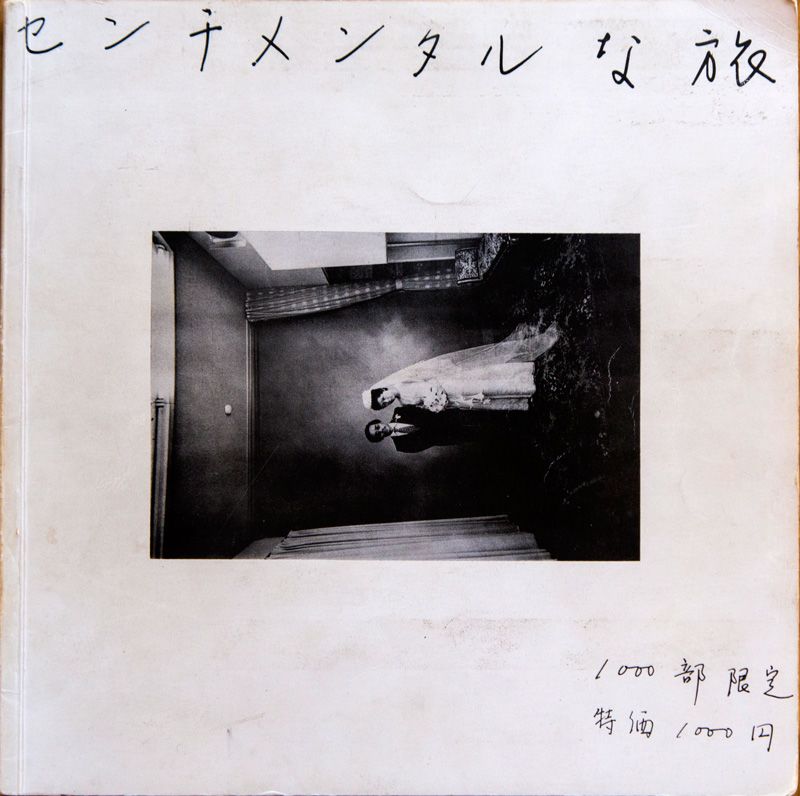

During his Dentsu years Araki worked by day as an advertising photographer while engaging in guerilla photography on the side. He used the Dentsu studios to shoot nude photographs, which he showed in exhibitions and subsequently distributed in his handmade 1970 photo collection Zerokkusu shashinchō (Xerox Photo Book). As written in the title, it was produced on a Dentsu photocopier. The most important of his guerilla works, however, was Senchimentaru na tabi (Sentimental Journey, 1971), a self-published album of photographs he took of his young wife Aoki Yōko, a former Dentsu colleague, on their honeymoon trip to Kyoto and Kyūshū.

Sentimental Journey is structured like a shishōsetsu, or “I-novel,”sometimes called a “personal novel,” a Japanese literary form in which the first-person narrator delves deep into the intricacies of personal relationships. In his short comments that served as the preface, Araki wrote that he had created the collection because, as he put it, “I believe it is the ‘I-novel’ that is the very closest artistic form to photography.”

The photographs in Sentimental Journey function as the text of an “I-novel” might, delicately stitching together the story of the artist’s relationship with a close other. He would later dub the technique shishashin, rendered in English as “I-photography” or “personal photography.” The form went on to become one of the important currents running through Japanese photographic expression.

The collection does not simply unveil the heart of Araki and Yōko’s relationship. It stands alone as a universal, almost mythological, tale that leads the viewer from the world of the living into the world of the dead, and back out again into the world of life.

Scandalous Nudes

Araki left Dentsu in 1972 to go freelance, and soon his distinctive black glasses and moustache were popping up all over Japan’s mass media. It was also at this time that he created his public persona of “Genius Arāki,” and started dabbling in a wide range of fields. His scandalous nudes kept him constantly in the spotlight, and he was developing a rather dubious public reputation. At the same time he was beginning to acquire an extremely high reputation in other quarters. When the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo held its landmark Fifteen Photographers Today exhibition in 1974, Araki was picked to be one of the exhibiting artists.

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print.(© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print.(© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)

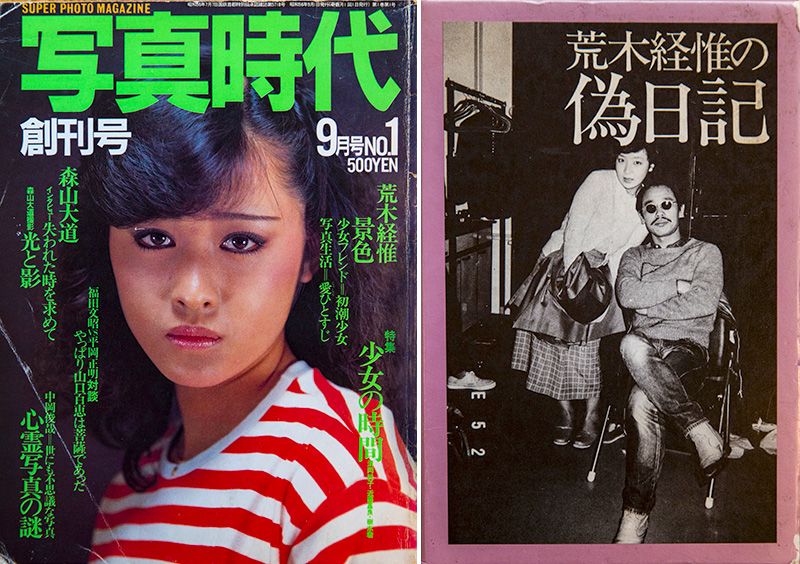

In 1981 the publishing house Byakuya Shobō launched a controversial new photojournalism magazine called Shashin jidai (Photography Age). At one point Araki had three series running concurrently in its pages—Keshiki (Landscapes), Shōjo Furendo (Young Lady Friends), and Araki Nobuyoshi no Shashin Seikatsu (Araki Nobuyoshi’s Photographic Life)—as he threw all his energy into expanding the boundaries of his creative world. Photography Age primarily catered to a young male readership with erotic photographs and articles, but also published in its vibrant pages Araki’s works and ambitious photography by other outstanding artists of the day, such as Moriyama Daidō, Kurata Seiji, and Kitajima Keizō. When we look at the photo collections Araki published during this period—works like Araki Nobuyoshi no nise nikki (Araki Nobuyoshi’s Fake Diary; 1980), Shashin shōsetsu (Photo Novel, 1981) and Shōjo-sekai (Girls’ World, 1984)—we can see how he continued to refine his methodology of blurring the boundaries between real-world events and fabrication, forcibly converting everything that caught his eye into his own “personal photos.”

Inaugural issue of Photography Age (left) and Araki Nobuyoshi’s Fake Diary (right).

Inaugural issue of Photography Age (left) and Araki Nobuyoshi’s Fake Diary (right).

The Photographic Face of Japan

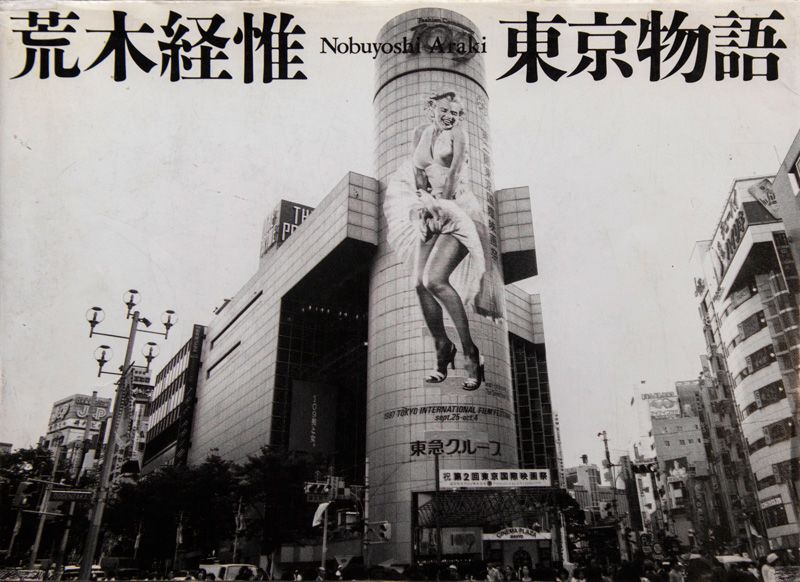

Photography Age was shuttered in 1988 following a stiff warning from the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department over its lurid nudity. Yet Araki continued to publish a series of outstanding collections of his own, including Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo Story). This work overlaid the transformation of the city in which he had been born and raised with the changing face of Japan itself, as the nation transitioned from the wartime and postwar Shōwa era (1926–89) to the Heisei era (1989–).

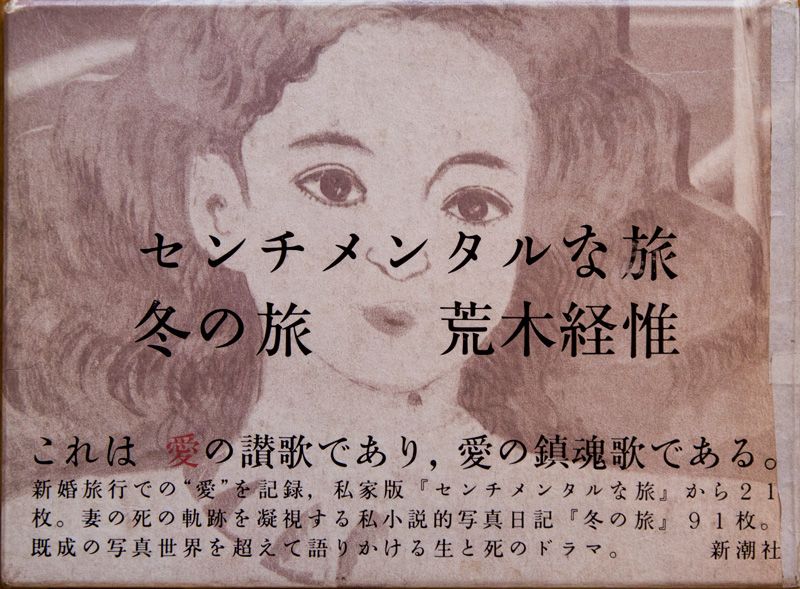

However, it was also around this time that Araki faced a personal catastrophe. His wife Yōko, a constant companion of 20 years, was diagnosed with uterine cancer and passed away in 1990. As a photographer, Araki embraced this sudden reversal of fortune, seeking to ride out the crisis by channeling it into his work. In 1991, he published those results in his powerful collection Senchimentaru na tabi: Fuyu no tabi (Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey, 1991), coupling the photographs taken 20 years earlier for Sentimental Journey with his Winter Journey photo diary of date-stamped photographs shot with a compact camera before and after Yōko's death. The exquisitely polished photographs and text were a comprehensive statement of all that Araki had gained and achieved in his unremitting pursuit of “personal photography.”

Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey.

Sentimental Journey/Winter Journey.

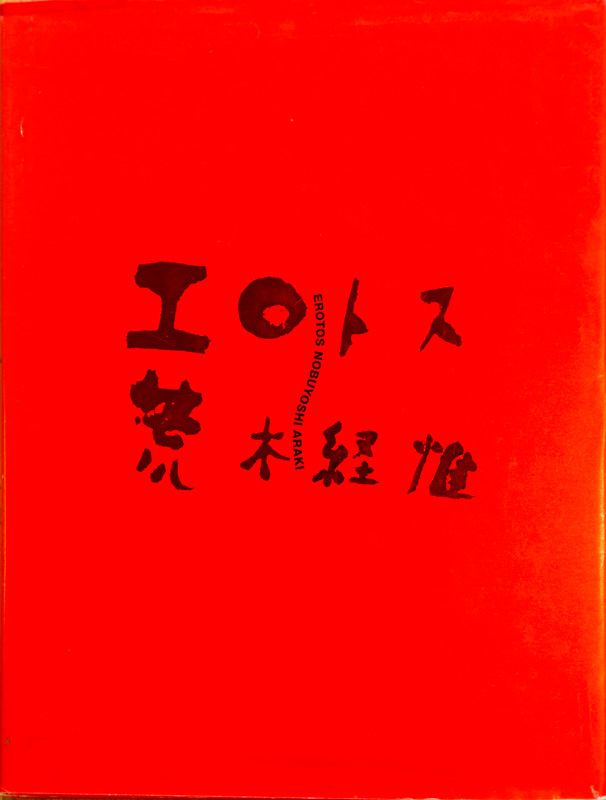

Yōko’s death marked a turning point for the artist. Araki launched himself into what he called a “second round” of work, seeking ever-greater heights of photographic expression. The collections published during this period of his life—Tokyo rakkī hōru (Tokyo Lucky Hall, 1990), Kūkei/Kinkei (Laments: Skyscapes / From Close-range, 1991),and Erotosu (Erotos, 1993)—are all powerful masterpieces, buzzing with creative tension.

It was also during this period that Araki’s work finally began to be recognized abroad, beginning with the AKT-TOKYO 1971–1991 exhibition at Forum Stadtpark in Graz, Austria (an exhibition that later toured Europe). It was followed soon after by large solo exhibitions of Araki’s work in Vienna, Paris, Rome, Taipei, London and other world cities.

Back home as well, the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo held the one-man Araki exhibition Senchimentaru na shashin, jinsei (Sentimental Photography, Sentimental Life), while Heibonsha launched the monumental Araki Nobuyoshi shashin zenshū (The Works of Nobuyoshi Araki) in 20 volumes over the course of 1996–97. These and other shows and publications cemented once and for all Araki’s reputation as one of Japan’s foremost contemporary photographers.

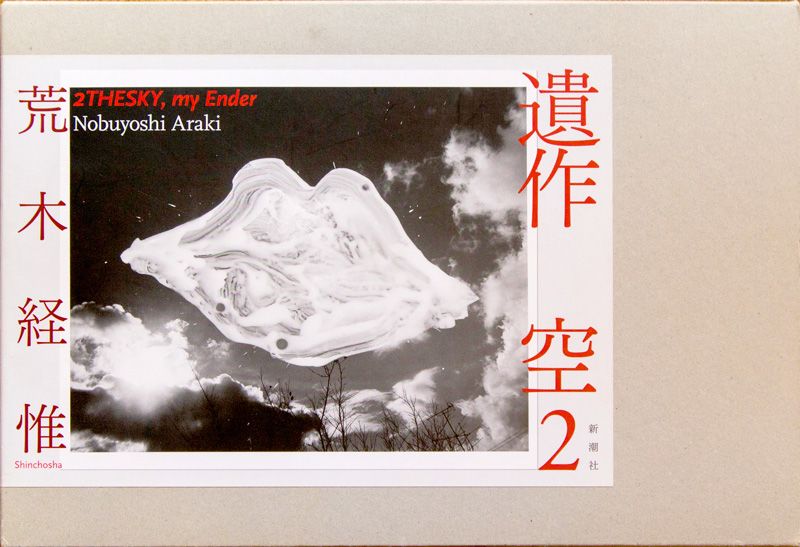

Even with all these accomplishments behind him, Araki’s daring spirit of experimentation shows no sign of weakening. Since the turn of the century, his photographic expression has become ever more freewheeling as he has begun to energetically manipulate his photographs, painting over them, writing on them, and creating photo collages. He now sometimes holds shows purely as a painter, or even a calligrapher. His 2009 Isaku: Sora 2 (2TheSky, My Ender) is a huge collection of 254 works created between January 2009 and August 15 of that year that is almost a visual diary. In it, photographs, paintings, and collages merge into one harmonious whole as Araki’s style of freely mixing and merging Eros and Thanotos achieves a unique pinnacle of its own.

Undiminished Creative Aspirations

In 2008 Araki was hospitalized and underwent surgery for prostate cancer. In 2010 his beloved cat Chiro died at the great age of 22. That loss was followed in 2011 by the Great East Japan Earthquake, and in 2013 by an obstructed retinal artery that cost Araki most of the vision in his right eye. For many years now, the course of Araki’s life has been full of negatives. It seems almost as if that exquisite balance of Erotos that the artist has maintained for so many years is now tilting inexorably toward Thanotos. Yet when we view his most recent photo series —works like Tōkyō zenritsugan (Tokyo Prostate Cancer, 2009) documenting the days before and after his surgery, the heart-rending record of Chiro’s battle with illness in Chiro aishi (Chiro Love Death, 2010), or his 2014 Sagan no koi (Love on the Left Eye), in which Araki blacks out the right half of his negatives with a marker pen—we can see how the artist continues to create to this day, his flourishing creative energy undiminished.

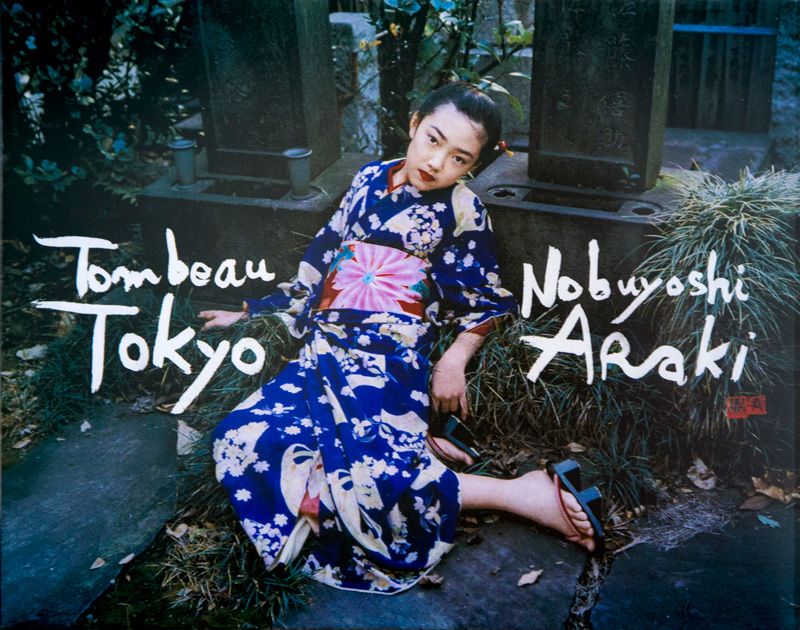

In 2014, Araki held three linked exhibitions titled Ōjō shashin (Paradise) at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, the Niigata City Art Museum, and the Shiseido Gallery in Tokyo. In these shows he presented powerful new works, including his “Road” photo series shot looking directly down at the street below from the apartment where he lives (published later that year in the collection Dōro (Road, 2014), and his Higashi no sora (Eastern Sky) series created following the 2011 earthquake by continuously shooting the sky in the direction of stricken Fukushima. From April to September 2016, the Musée Guimet Asian art museum in Paris presented a major respective titled simply Araki that also included 98 new works, again impressing European audiences with the immense power of his creative world.

Tombeau Tokyo, containing works displayed at the Musée Guimet Araki retrospective.

Tombeau Tokyo, containing works displayed at the Musée Guimet Araki retrospective.

Araki was once a minor figure known only to the cognoscenti. He is now a major global artist who continues to labor on the frontlines of photographic expression. Yet over all these long years his fundamental creative style has never changed. At age 76 there is some concern about Araki’s health, but when I met him recently he was full of vim and vigor. “This year I want to show new work in at least five places,” he declared in great sprits. I suspect that Araki will continue to play brilliantly with different images, sometimes laced with humor, and will continue to pull his viewers deeper into his own magical world for years still to come.

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print. (© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)

Print from Tombeau Tokyo, 2016. Gelatin silver print. (© the artist/courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery)