Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

A Thousand Cranes Take Flight

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Morning Banquet

The observatory at the Akan International Crane Center outside of Kushiro in Hokkaidō has a sweeping view of an expansive snow field where red-crowned cranes come to feed every year from November to March.

Today around 50 cranes are busily picking at the feed that has been scattered for them. They are soon joined by a flock of whooper swans descending from the sky, a small herd of Japanese deer, and more than 100 mallards. The morning banquet has begun.

Japanese deer join the cranes in their feeding grounds.

Japanese deer join the cranes in their feeding grounds.

Two cranes commence an elegant dance on the snow. They call out to each other in unison and prance about. Their breaths escape from their bills in white frosty puffs. Suddenly, the two cranes simultaneously kick at the snow and leap high into the air. This is the fascinating mating dance of the red-crowned crane.

A pair of cranes leap high into the air in an elegant mating dance.

A pair of cranes leap high into the air in an elegant mating dance.

Back in 1950, the farmer who owned this land noticed a number of large white birds pecking at his cornstalks. When he realized they were the red-crowned cranes that were thought to be extinct, he scattered corn on the field, but they showed little interest until one day in 1952, when he saw them eating the corn in the midst of a morning snowstorm. This was the start of the feeding program that continues to this day.

The Akan International Crane Center was built later for research and educational purposes. The sight of hundreds of cranes feeding on the field is a spectacular one that regularly attracts tourists from all parts of Japan and the world. The crane are now considered one of east Hokkaidō’s three must-see “white tourist attractions,” along with white swans and the seasonal white ice drift in the Sea of Okhotsk.

The Tsurui village crane sanctuary is a popular Hokkaidō tourist attraction.

The Tsurui village crane sanctuary is a popular Hokkaidō tourist attraction.

1,800 Strong

In the observatory in front of the center, a number of people peer through binoculars while clicking counters in their hands. These people are members of the Red-Crowned Crane Conservancy (RCC), a nonprofit group based in Kushiro, Hokkaidō, that is dedicated to conserving the rare species. They have been counting the cranes at the sanctuary for the past 32 years, most recently at the beginning of 2017. January and February are the months of Hokkaidō’s most bitter cold, with temperatures regularly plunging below –20ºC. But this is when most of the red-crowned cranes come to the feeding grounds, making it the easiest time to count their numbers.

The RCC is currently headed by Momose Kunikazu, who leads about 70 volunteers in the winter census taking. The volunteers range in age from 19 to 85 and include students, adults, veterinarians, researchers, zoo keepers, and translators. Some come from Tokyo and Hyōgo Prefecture. And some have been regular participants in the census taking since it first began. All share a common love for the red-crowned crane.

RCC Chair Momose Kunikazu (in pink coat) with volunteers before the census taking.

RCC Chair Momose Kunikazu (in pink coat) with volunteers before the census taking.

The volunteers bundle up in layers of clothing and warm boots and arm themselves with pocket warmers to stave off the cold. They divide up into three groups to count the cranes that are in the feeding grounds, airborne, and in the nesting areas. The figures are rigorously checked and rechecked, and though the final data has not yet been made public, it is estimated that in 2017 they counted the highest number ever, around 1,800 cranes.

Counting the cranes at the feeding ground in front of the Akan International Crane Center annex.

Counting the cranes at the feeding ground in front of the Akan International Crane Center annex.

The census taking in the depths of winter is followed by aerial surveys in search of nests and pairs of cranes in the April–May breeding season. Planes are chartered to fly over possible nesting grounds for mapping and photographing the nests and surrounding habitat. This information is used later, in the early summer, to capture and band newborn chicks and fledglings. The process involves waves of volunteers moving into the nesting grounds to capture the young birds, take blood samples, and attach bands to their legs. This time, it is not the cold but the mosquitoes, horseflies, and ticks that pester the volunteers as they search out the nests while talking to each other with transceivers.

Preparing to board a light plane for an aerial survey of nesting sites. (Courtesy Momose Kunikazu)

Preparing to board a light plane for an aerial survey of nesting sites. (Courtesy Momose Kunikazu)

The bands make it possible to identify individual cranes, gather data on life expectancies and reproduction rates, and keep track of cranes when they change partners. All of this has greatly helped to increase the information on crane behavior and habitats. The blood samples are also helping to identify successive generations of cranes.

The RCC’s survey of the red-crowned cranes is one of the longest-running studies of its kind in the world. Researchers from China, Korea, and Russia, countries that also have red-crowned crane populations, are frequent participants in the RCC surveys. These visitors express admiration for the Japanese volunteers who willingly work in freezing cold weather. In 2016, the RCC won a Japan–South Korea International Environment Award, presented to individuals and groups contributing to environmental conservation in East Asia.

Revered and Admired

The Japanese and Chinese, in particular, have always had great esteem for the elegant and refined red-crowned crane. The crane is depicted along with turtles in the etchings on ancient dōtaku bronze bells of Japan’s Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD). And the eighth-century Man’yōshū collection of Japanese poetry has poems by 46 poets referring to tazu, a term used for large, white water birds like swans, but now believed to allude in most cases to cranes.

Red-crowned cranes were also frequently depicted in twelfth-century Yamato-e art, appearing as motifs in Buddhist-themed paintings, sumie ink brush paintings, fusuma sliding door art, and woodblock prints. Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800), a painter of the Edo period (1603–1868), had a particular affinity for painting birds and flowers and often included red-crowned cranes in his work.

The crane is an auspicious symbol, and art historian Okanobori Teiji (1888–1976), in his Mon’yō no jiten (Encyclopedia of Patterns), asserts that it is probably the most widely used motif in Japanese arts and crafts. Cranes are used on noshigami wrapping paper and as mizuhiki decorative cording. They can be found in family crests and kimono patterns and on lacquer and ceramic ware, as well as on traditional weapons and armor.

The crane also figures in traditional folk stories. Tsuru no ongaeshi (The Grateful Crane) is well-known throughout Japan and has even been made into musicals and an opera. The crane is cited as a symbol of long life and is also regarded as a symbol of peace, the most famous example being the 1,000 origami cranes folded by Sasaki Sadako, who died at the age of 12 due to radiation sickness following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Hunted by the Shōguns

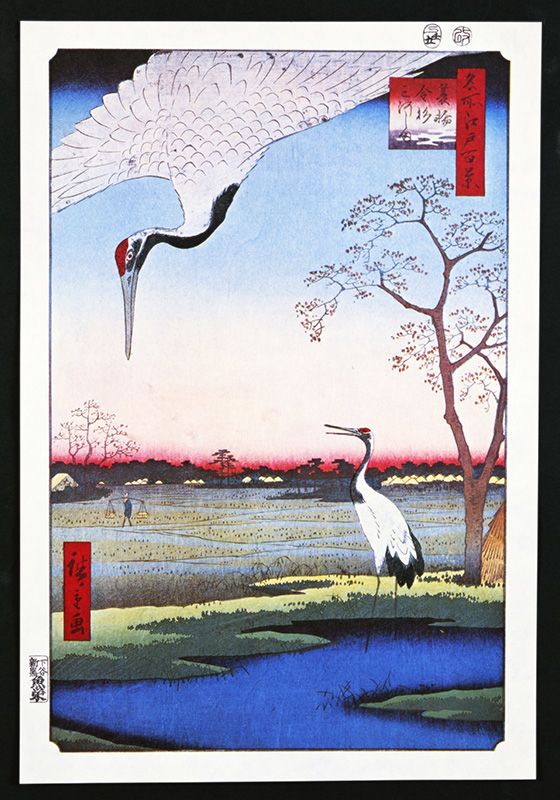

Utagawa Hiroshige’s 1857 print Minowa, Kanasugi, Mikawashima shows cranes along the bank of what is thought to be the Arakawa. (© Aflo)

Utagawa Hiroshige’s 1857 print Minowa, Kanasugi, Mikawashima shows cranes along the bank of what is thought to be the Arakawa. (© Aflo)

The ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) included scenes of cranes in his series, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. The one shown here is a novel design showing a crane descending into the frame. This particular print, made in 1857, is believed to show the marshy area along the south bank of the Arakawa, a river that provided hunting grounds for the Tokugawa shōguns.

Crane meat was considered a high-class product and crane hunting was rigorously regulated. A tsuru onari was a falconry hunting expedition for cranes exclusively reserved for the shōgun, and the red-crowned cranes were carefully protected. Known habitats were encircled with bamboo fencing and local residents assigned the task of guarding the area. The torimi nanushi was responsible for general oversight while others were charged with feeding the cranes and watching out for stray dogs. Kite-flying in the area was prohibited for fear it would startle the cranes.

The first Tokugawa shōgun, Ieyasu (1542–1616), was particularly fond of falconry and visited the hunting grounds frequently. Even the fifth shōgun, Tsunayoshi (1646–1709)—an animal-lover famed for instituting corporal punishment for the killing of dogs—enjoyed falconry. The Tokugawa regularly offered up the cranes they captured as meat for the imperial family, and served what was left at banquets for their daimyō vassal lords. The daimyō also made it a regular practice to curry favor with the shōguns by presenting them with crane meat.

Cranes were hunted over a broad region, from the shores of what is now Tokyo Bay to the Arakawa river basin and to marshlands further inland. In the carefully chronicled hunts from 1611 to 1790, a total of 183 cranes—around one each year—were captured.

Crane meat was considered to have medicinal properties, and in 1677, a scandal erupted when villagers in what is now the town of Tone in Ibaraki Prefecture captured a crane to provide meat for a sick family member. A whole family of 10 villagers, including children, was condemned to death. Edo-period records note more than eight incidents of crane poaching, but not all of the culprits were executed. When a culprit was of the samurai class, he was more likely to be put under permanent or temporary house arrest.

A Source of Food

There is a long history of eating crane meat in Japan. This is confirmed by red-crowned crane bones found at various historical sites and middens in Aomori, Iwate, and Ibaraki Prefectures, and by ancient records dating back to the Heian period (794–1185). Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241), one of the editors of the Shin Kokin Wakashū poetry anthology, writes of eating crane meat in a 1227 diary entry.

By the Edo period, crane meat was out of the reach of the common people. Far away in Ezochi (Hokkaidō), however, cranes were avidly hunted and their meat salted and shipped to the various domains throughout Japan. Matsuura Takeshirō (1818–1888), who explored Ezochi extensively at the end of the Edo period and into the Meiji era and is credited with renaming the region Hokkaidō, reports seeing large red-crowned crane populations in the marshy regions along the Ishikari and Teshio rivers.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Edo-period prohibitions against bird hunting and hunting with guns were lifted. This led to such extensive overhunting that by the time a law was enacted in 1892 prohibiting the hunting of any kind of crane, they had disappeared in most parts of Japan. By the Taishō period (1912–26), the red-crowned crane was thought to be extinct on the main Japanese island of Honshū.

Bringing the Population Back to Health

In 1924, a few red-crowned cranes were spotted in the Kushiro marshlands of Hokkaidō, and in 1935, the cranes and their habitat were declared Natural Monuments. Their numbers continued to dwindle, however, until they seemed to completely disappear. Nakanishi Godō (1895–1984), founder of the Wild Bird Society of Japan, traveled to Hokkaidō where he spent a day searching for the cranes only to report that he came upon none.

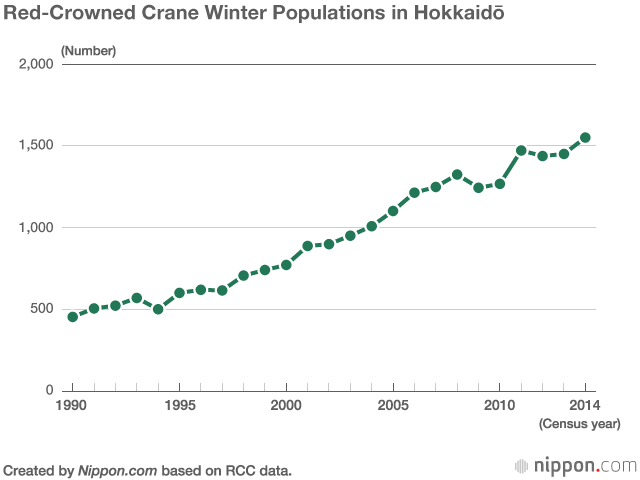

Again, in 1952–53, a large group of more than 10,000 students and adults searched again for the red-crowned crane, but were only able to confirm sightings of a flock of 33 cranes. At this point, the government rushed to declare the red-crowned crane a Special Natural Monument. National and local governments launched measures to protect the species and the numbers of the cranes slowly increased from 178 in 1962 to 424 in 1988 and 740 by the turn of the century.

Encouraged by the growing numbers, several conservationist groups began a national trust movement to purchase and preserve the habitats of the red-crowned crane. They also set about to cultivate buckwheat fields, transplant Japanese wild parsley, and release pond loaches to provide food for the cranes. In 1993, the red-crown crane was designated a rare species—an improvement from its previous, more endangered status.

By 2004, the hoped-for benchmark of 1,000 cranes had been reached, and by 2016, the number was 1,800. The winter feeding grounds played a major role in this recovery, as previously the number of cranes had tended to decline in the winter months when food was scarce.

The author conducts an interview at the Tsurui village feeding grounds.

The author conducts an interview at the Tsurui village feeding grounds.

The practice of putting out feed for the cranes, which began in 1952, has spread to other parts of Japan. There are currently 23 feeding grounds, 3 managed by the Ministry of the Environment and 20 small- and medium-sized grounds managed by the Hokkaidō prefectural government.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 3, 2017. Banner photo: Red-crowned cranes take off from the feeding grounds of the Akan International Crane Center annex. All photos © Nippon.com except where otherwise noted.)