Remarkable Recovery: The Modern History of Japan’s Environment

Crane on the Rubbish Heap: The Challenges of Continuing Conservation

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Profile in Elegance

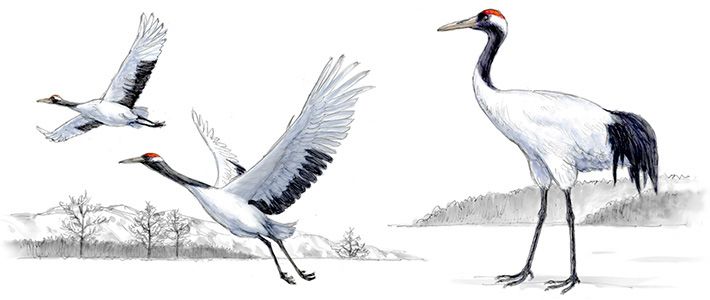

The red-crowned crane is not the only variety to be found in Japan. Others include the white-naped cranes that winter in Izumi, Kagoshima Prefecture, and the hooded cranes that winter there as well as in Shūnan, Yamaguchi Prefecture. The Eurasian, Demoiselle, Siberian, and Sandhill cranes also appear in Japan on occasion. But among all of these, the red-crowned crane reigns supreme, standing up to 150 centimeters tall and boating a wingspan of some 240 centimeters. Its body is white, its face, just under the eyes and down the throat, a black streak. Bright red skin, like a rooster’s comb, sits like a cap on its head. The character tan 丹 in the red-crowned crane’s Japanese name, tanchō (丹頂) means “red.” This striking coloration of white, black, and red creates a most elegant and majestic aura.

The red-crowned crane has breeding grounds in southeastern Siberia, northeast China, and the Kushiro and Nemuro regions of Hokkaidō. The continental cranes winter on the Korean peninsula and in eastern China, but those in Hokkaidō stay there year-round. Designated a Special Natural Monument. (Illustration by Izuka Tsuyoshi)

The red-crowned crane has breeding grounds in southeastern Siberia, northeast China, and the Kushiro and Nemuro regions of Hokkaidō. The continental cranes winter on the Korean peninsula and in eastern China, but those in Hokkaidō stay there year-round. Designated a Special Natural Monument. (Illustration by Izuka Tsuyoshi)

The red-crowned crane is omnivorous and will eat just about anything, ranging from insects and their larvae to shrimp and crabs, land and pond snails, loaches, carp, dace, frogs, the young chicks of other birds, field mice, and such plants as Japanese parsley, chickweed, and Mongolian oak.

During the breeding season from March to May, the female lays one or two eggs in a dish-shaped nest roughly 150 centimeters in diameter built of dried reeds, grass, and branches. Both the male and female take turns guarding the nest, located in the shallows edging the marshlands, and warming the eggs, which hatch in 31 to 36 days. The chicks are able to fly in about 100 days.

Distribution in East Asia

Besides Japan, the red-crowned crane can be found in southeast Russia, in northeast China, along the northern border of South Korea, and in all parts of North Korea. The cranes breed in the summer in nesting grounds located along the Amur and the middle reaches of the Ussuri rivers in China and Russia. In the winter, they migrate to the Korean peninsula and the southern regions of the Yangzi (Yangtze) River. While it is estimated that there is a continental population of around 1,700 red-crowned cranes in China, the two Koreas, Russia, and Mongolia, the number in Japan is greater than this, making it the largest red-crowned crane population in the world.

Efforts to protect the red-crowned crane on the continent lag behind those in Japan. In fact, the exact numbers of the crane populations are unknown in many of the continental sanctuaries. The birds are seeing their habitats shrink due to field-burning in the Amur River basin that alters their living environment and destroys the materials they need for nest-building, as well as clearing to create farmland in China. The crane populations there are dwindling as a result. Crane populations in other areas, too, are likewise falling due to drying up of marshlands, bush fires, poaching, and lack of food.

Researchers are also concerned that most of the banded cranes released in Russia to migrate to China are not returning. The Chinese value the red-crowned crane as an auspicious symbol and there have been eyewitness accounts of captured cranes being kept as pets by wealthy Chinese. In the same vein, there is a sanctuary where groups of red-crowned cranes are put on display in a show, and though the plan was eventually abandoned, Olympic planners were considering a mass release of red-crowned cranes instead of doves at the opening ceremonies for the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing.

Over just the past few years, a handful of red-crowned cranes have been sighted in Akita, Ishikawa, and Miyagi Prefectures that appear, following genetic analysis, to have come from the Asian continent. Thanks to the greater accuracy of recent genetic studies, it is now known that there are major differences between the red-crowned cranes of the continent and those native to Japan.

For three consecutive years starting in 2007, the Red-Crowned Crane Conservancy (RCC) invited Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Russian, and US conservationists to international workshops to discuss ways to collaborate in protecting the species. In 2009, the International Red-Crowned Crane Network was established, and there continues to be active interaction among those researching the rare crane.

Paradise in the Demilitarized Zone

The flocks of cranes that winter on the Korean peninsula were driven to near-extinction by the Korean War, their numbers dropping at one point to only around 150. They were saved, however, by the emergence of an unexpected sanctuary, the strife-free demilitarized zone at the border between the two Koreas.

When a truce brought the fighting to an end in 1953, the peninsula was divided into north and south, separated by a 248-kilometer strip of land about 4 kilometers across. The DMZ is a rich natural expanse of 907 square kilometers through which flow six rivers, with a plains area and marshlands to the west and mountainous terrain to the east.

For over 60 years, human entry into the DMZ has been barred by barbed wire and land mines. This has allowed the land to recover from the ravages of war and has brought back the animals. Thanks to the efforts of conservation groups in South Korea, the number of red-crowned cranes in the DMZ has increased from 200–250 in the 1970s to 850 in 2006, and more recently to more than 1,000.

Other rare animals, such as the endangered musk deer and the Amur leopard, have also been spotted in the DMZ. The area has also been found to be a habitat for the Eurasian otter, once thought to be extinct.

Without human intervention, it is amazing to see how nature can revive in such a short time. This brings to mind the way in which wolves, bears, and other wild animals have made their way back to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine. In Fukushima, site of the Fukushima nuclear accident, wild boar and mice have grown to such numbers that they are destroying crops and becoming a major problem for local farms.

The Dilemma of Overpopulation

In the Kushiro marshlands of Hokkaidō, the growing number of red-crowned cranes has likewise become a problem as they increasingly encroach on human territory due to the reduction and deterioration of their own habitat. Overcrowding is raising the risk of infectious disease, and cranes are eating and destroying crops, electrocuting themselves on high-voltage wires, and being involved in an increasing number of traffic accidents.

It is no longer unusual to see cranes boldly crossing highways and train tracks. In the years 1964, 1965, 1972, and 1973, roughly 10% of the local crane population died from traffic accidents. Some cranes, attracted to cowsheds by the feed, have died falling into slurry tanks of cow dung and other waste.

Outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza in the winters of 2010–11 and 2016–17 continue to be reported in wild bird populations. Due to the possibility that the virus is spreading from white-tailed eagles that come in to eat the fish that are scattered as feed for the cranes, this practice has been stopped in some areas.

A white-tailed eagle in the feeding grounds for red-crowned cranes.

A white-tailed eagle in the feeding grounds for red-crowned cranes.

Cranes on the Rubbish Heap

Accustomed to being given food, there are some clever cranes who have lost their fear of humans and chosen to make themselves at home in cowsheds where they can share the feed put out for the cattle. Just about every cowshed in the proximity of a crane habitat has such uninvited guests. A common sight these days is a row of cattle faces down in their feed bins matched on the opposite side by a row of cranes picking at the same feed.

Also to be seen are cranes picking at refuse and compost piles on livestock farms, living incarnations of hakidame ni tsuru, or “crane on the rubbish heap,” a Japanese phrase meaning a thing of beauty or elegance found in an unlikely place.

Cranes today are seeking sustenance in places outside the natural environment, such as this farm rubbish heap. (© Nippon.com)

Cranes today are seeking sustenance in places outside the natural environment, such as this farm rubbish heap. (© Nippon.com)

There are some farms where the thieving cranes are ignored because they are a protected species, but there are also farmers who chase them away, seeing them as pests that forage their corn fields and trample their barley. On livestock farms, the cranes poke holes in the plastic covers on the hay being dried for cattle feed and frighten young, jittery cows who injure themselves trying to get away from the flapping birds. Not a few frustrated farmers are pointing out how the crane population has grown and are asking why there need to be more.

No More Free Handouts

Many of the marshlands that were such ideal nesting grounds for the red-crowned crane have disappeared due to the cultivation and development that has been taking place since the late 1800s. Even the marshlands that remained in eastern Hokkaidō into the early postwar era have diminished by roughly 40% since the 1950s. Caught between their own increasing numbers and their decreasing habitat, red-crowned cranes are suffering a “housing crisis” of sorts.

There are more than 450 pairs of red-crowned cranes nesting in the marshlands of eastern Hokkaidō. While in the summer they spread out to other parts of Japan, in the winter more than 90% of that number congregate in the marshlands of Kushiro, and half of those cranes are dependent on just three feeding grounds where 33 tons of feed is scattered every year to get them through the bitter winter.

The cranes are losing out, too, on the easy access they once had to crops and animal feed. Forced by the changing times and lack of successors, many farmers are giving up on farming altogether. In livestock farming, the trend is for several farms to join forces to become incorporated and livestock workers commute rather than living on the farms. Cowsheds are turning into clean, sterile environments that the cranes cannot enter.

In fiscal 2013, the Ministry of the Environment formulated a 20-year plan to phase out the Hokkaidō feeding grounds, forcing the red-crowned crane population there to disperse and create a flock that would winter on the main Japanese island of Honshū. This plan kicked off in fiscal 2015 with a move to reduce the feed scattered in the feeding grounds to half the original volume over a 5-year period.

Ironically, in this very first year of the plan’s implementation, a typhoon knocked down local dent corn crops, providing the cranes with an unexpected feast. The cranes abandoned the feeding grounds to flock to the ravaged corn fields.

The Contradictions of Conservation

Momose Kunikazu, chair of the RCC, has long been fascinated by the cranes. A wild-bird researcher, Momose has also been involved in efforts to conserve the Japanese crested ibis and the short-tailed albatross, and was invited to spend some time at the International Crane Foundation headquarters in Wisconsin in 1980. Since then he has concentrated on the red-crowned crane in his research and conservation efforts.

Today, Momose finds himself in a major quandary. The feeding program has been successful, but the outcome is that cranes are becoming overcrowded and are at risk of disease. While the cranes are no longer endangered, and have become a new tourist attraction, at the same time, they are ravaging the crops of local farms.

Momose is worried. “We can reduce their feed to encourage the cranes to disperse, but the marshlands that provide them with a safe habitat are not available throughout Japan. There are actually very few areas where they can subsist on their own. In fact, they may become even greater threats to local crops, inflicting even more damage. The question is how the cranes and humans can coexist. We need to explore methods of conservation based on scientific data that will continue to be effective thirty to fifty years from now.”

This has been one of his objectives in establishing the nonprofit RCC, but basic research is a low-profile undertaking that takes time to show results, and now that the red-crowned crane is no longer endangered, subsidies and donations are harder to come by.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 8, 2017. Banner photo: The mating dance of the red-crowned crane. All photos © Nishioka Hidemi except where otherwise noted.)