Outlaw Appeal: The Yakuza in Film and Print

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Outrage Coda, the final instalment in Kitano Takeshi’s yakuza trilogy, hit screens in Japan in October 2017. As the Japanese tagline to the first film Outrage (2010) put it, “everyone’s a villain” (zen’in akunin), and betrayal follows betrayal in the series’ gang conflicts. Outrage and Outrage Beyond (2012) together made more than ¥2.2 billion at the box office.

When Outrage Beyond was released, Kitano spoke to the film website Outside in Tokyo. “Japan’s yakuza films began with the golden age of ninkyō [chivalry] movies and stars like Takakura Ken and Tsuruta Kōji. Then there was director Fukasaku Kinji’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series. . . . But this is where the evolution stopped.” Kitano saw his Outrage series as representing a new stage in the history of yakuza films.

Kitano Takeshi in Outrage Coda. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

Kitano Takeshi in Outrage Coda. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

The immensely popular yakuza films of the 1960s presented a nostalgic world of noble gangsters. These gave way to a new realism in the 1970s where stories were based on actual people and organizations. Most famous among these was Battles Without Honor and Humanity, the first in a series of films directed by Fukasaku.

A Yakuza Film Classic

Released in January 1973, the film starred Sugawara Bunta and took its narrative from a gang war that took place in postwar Hiroshima. It begins with the following monologue.

“A year after defeat, the savagery of war is gone, but new violence rises in the disordered land. To stand up against this lawlessness, people can only rely on their own strength.”

Francis Ford Coppola’s mafia film The Godfather, released half a year earlier, in July 1972, was a global megahit. It stung Tōei studio head Okada Shigeru into action, as can be seen in this interview published in the Kinema Junpō magazine in September 1972.

“I think what people want in 1972 is something with a strong sense of reality. Just like The Godfather. These movies have a different appeal from those produced through the star system. I’d like to make a big, realistic film at Tōei.”

The studio came up with Battles Without Honor and Humanity, which spawned four rapid-fire sequels by 1974. The record-breaking series continues to win new fans today.

US film critic Mark Schilling channeled his enthusiasm for the genre into his 2003 work The Yakuza Movie Book: A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films. He describes how yakuza films were initially looked down on by pundits, but that their directors have risen in critical esteem.

According to Schilling, the heroes of the ninkyō films were “the spiritual descendants of the silent-era gamblers who had upheld traditional values while slicing through crowds of opponents with swift, deadly swords. Their enemies, however, were not only the usual bad gangsters who flouted the gang code but also their corrupt allies in business, government, and the military. These heroes defended not only the gang boss or the occasional helpless widow but also the exploited workers of Japan’s belated industrial revolution.”

As the yakuza films of the 1970s opted for deeper realism, he continues, “the focus shifted to the postwar period itself, discarding much of the mythological baggage of the past. Now, the approach was that of the news cameraman, recording the carnage but refraining from judgment. A new hero appeared, whose loyalty was conditional and who lived for himself—and to hell with the consequences.”

The success of Fukasaku’s film took Tōei into an era of realism, but it did not last long. In 1973, Yamaguchi-gumi sandaime (Yamaguchi-gumi: The Third-Generation Leader), starring Takakura Ken, told an authentic yakuza story without even changing the names. The use of the autobiography of Yamaguchi-gumi leader Taoka Kazuo as source material drew the ire of the police, though, and intervention by the authorities cut the planned trilogy short after its second installment, bringing the age of realism to a premature end.

The Outrage series has brought the yakuza genre new popularity after long years in the box-office doldrums. It has a contemporary appeal, unlike the pure fantasy of ninkyō movies or the almost nonfictional nature of the realistic films that followed them.

A scene from Outrage Coda. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

A scene from Outrage Coda. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

The Outrage Coda poster. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

The Outrage Coda poster. (© 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee)

Yakuza in Print

In the publishing world, yakuza-turned-author Abe Jōji’s book Hei no naka no korinai menmen became a bestseller in 1986. The novel was based on his prison experiences and adapted to both film—with the English title Guys Who Never Learn—and television. In the same year, Ieda Shōko’s book Gokudō no onna tachi (Yakuza Wives) was a big hit. The journalistic work about women in the yakuza world was also adapted, in greatly embellished form, to film and television. More recently, the manga series Ichi the Killer, featuring warring yakuza gangs, ran from 1998 to 2001 and was adapted into a notoriously violent film in 2001 by director Miike Takashi.

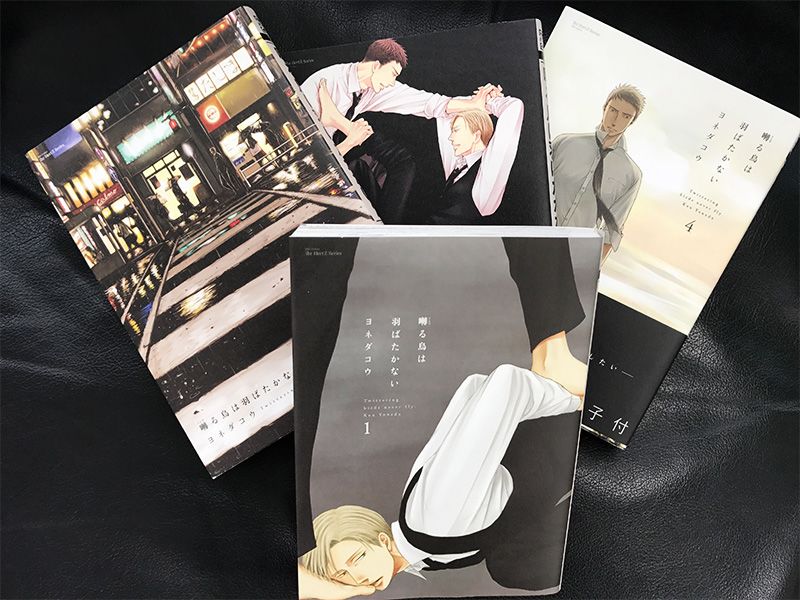

Perhaps surprisingly, there are even manga that mix the yakuza genre with “boys’ love”—comics portraying male-male relationships that are primarily marketed to women. One of the most successful of these is Saezuru tori wa habatakanai (trans. Twittering Birds Never Fly). It presents the story of a masochistic yakuza underboss and his bodyguard, a former cop. At the same time, it gives a highly detailed depiction of yakuza society.

Books in the Saezuru tori wa habatakanai (Singing Birds Don’t Flap Their Wings) series.

Books in the Saezuru tori wa habatakanai (Singing Birds Don’t Flap Their Wings) series.

Yakuza Documentary

Matsukata Hiroki and Umemiya Tatsuo, who both acted in Battles Without Honor and Humanity, discussed the state of the genre in the weekly Shūkan Gendai in 2015. Matsukata said, “For good or bad, society was more open-minded then. Unfortunately, it’s become difficult to make a yakuza film these days.” Umemiya responded, “I think a new yakuza movie would be a hit though. Japanese gangs still operate in the same way as back then and the yakuza world is perfect for an ensemble piece.”

Outrage successfully uses its ensemble cast in a realistic fiction that falls between ninkyō romanticism and the true-story-based films that followed.

A recent documentary offers another viewpoint on Japan’s criminal gangs. Yakuza to kenpō (Yakuza and the Constitution) questions whether gang members have human rights. It was produced by Tōkai Television Broadcasting and first broadcast in 2015. After garnering a huge reaction, it was shown as a film in small theaters across the country in 2016.

The yakuza in the film describe the hardships of their lives after a wave of legislation targeting gangs. They have had to shut down their bank accounts and cannot get insurance or enter their children into nurseries.

A scene from Yakuza and the Constitution. (© Tōkai Television Broadcasting)

A scene from Yakuza and the Constitution. (© Tōkai Television Broadcasting)

Documentaries like Yakuza and the Constitution provide a different perspective than fiction, however realistic, opening up further possibilities for understanding Japanese gangs.

(Originally published in Japanese on September 25, 2017. Text by Kuwahara Rika of Power News. Banner photo: A scene from Outrage Coda. © 2017 Outrage Coda Production Committee.)