Abu Dhabi’s Black Gold—and More—Lures Japan to the United Arab Emirates

Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

How Economic Diplomacy Won Oil Rights in Abu Dhabi

The Middle East and North Africa region is of overwhelming importance for Japan in regard to securing supplies of crude oil. Japanese oil diplomacy has scored a historic coup with a contract concluded this April between Japan’s INPEX Corporation, the Supreme Petroleum Council of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. The 40-year contract grants INPEX, an oil and gas exploration and production company, 5% of the output of the oil fields in Abu Dhabi’s ADCO Onshore Concession, which comprises 11 oil fields in production and 4 that are under development. INPEX’s share of their output will amount to between 80,000 and 90,000 barrels a day.

Japan has a close relationship with the United Arab Emirates and especially close ties with the emirate of Abu Dhabi. About 40% of the crude oil that Japan has secured since World War II through independent development has been from Abu Dhabi wells. Contracts that cover 60% of Japan’s oil rights in the emirate lapse, however, in 2018, so the new contract is a hugely important step in maintaining Japan’s oil lifeline.

The UAE and Japan have reaffirmed their mutual commitment through reciprocal visits by their leaders. Abe Shinzō visited the UAE as prime minister in 2007, during the first Abe administration, and again in 2013. From the UAE, Abu Dhabi’s crown prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan visited Japan in 2014.

Japan imported 840,000 barrels of oil a day from the UAE in 2014. That was 24% of Japan’s total oil imports, and the UAE was the nation’s second-largest supplier, after Saudi Arabia.

The UAE is the world’s sixth-largest producer of crude oil. Abu Dhabi’s onshore oil fields yielded 1.6 million barrels a day in 2014, and development under way will increase their daily output to 1.8 million barrels in 2017. With the ADCO contract, INPEX becomes the first Japanese company to participate directly in developing and producing oil at a large onshore concession. It won the contract through competitive bidding among 10 companies, including oil “majors,” China National Petroleum Corporation, and Korea National Oil Corporation.

Fortuitous Geography

INPEX’s ADCO contract marks Japan’s first large acquisition of oil rights since 2009. It will increase Japan’s supply of crude oil from directly owned rights to about 15% of the nation’s consumption. And the ADCO concession is immensely appealing for other reasons, too.

Abu Dhabi’s location makes it possible to transport its crude oil to Japan without traversing the Strait of Hormuz. That is important, since the strait is a potential bottleneck in the event of serious unrest. Drilling and operating wells at the concession’s onshore setting is far less costly, meanwhile, than developing offshore oil resources.

Japan was apparently an attractive counterparty for the UAE. “The UAE awarded the contract,” emphasized a Japanese embassy spokesperson in Abu Dhabi, “as a bridge to Japan. A politically moderate Arab nation, the UAE pursues a pragmatic approach in diplomacy, and its leaders regard Japan as a valuable long-term partner.”

A Market More than 10 Times Larger than Thailand’s

The Middle East and North Africa, as defined by the Japan External Trade Organization, comprise 22 nations that have a total population of 530 million people. JETRO projects that their aggregate nominal GDP will expand 4.4% in 2015, to $4,061.2 billion—more than 10 times larger than Thailand’s.

Robust population growth and a young demographic profile bode well for continuing economic growth in the Middle East and North Africa. Citizens younger than 20 years old account for about 40% of the aggregate population, and the working-age population will continue to grow until 2030. Consumption is therefore bound to expand steadily. JETRO projects that aggregate GDP in the Middle East and North Africa will surge 97% in the years to 2050, compared with predicted growth of 55% in India and 39% in the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Data from Japan’s foreign ministry reveals that the Middle East and North Africa had attracted 810 Japanese companies as of 2013. The UAE hosted the largest contingent, followed in order by Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Qatar. ASEAN hosted 10 times as many Japanese companies as the Middle East and North Africa. Yet the Middle East and North Africa is 70% larger than ASEAN in regard to market scale and twice as large as India. So the potential for expanded interchange with Japan is immense.

The UAE as a Magnet for People, Goods, and Capital

The UAE is an engine of economic growth for the Middle East and North Africa. It retained impressive political stability throughout the upheavals of the Arab Spring, which shook several nations in the region. The UAE thus attracted inflows of people, goods, and capital as a regional safe haven.

Abu Dhabi, the UAE capital, also possesses the bulk of the nation’s oil and natural gas resources. Dubai is the nation’s commercial center and the most populous of the UAE’s seven emirates. Abu Dhabi and Dubai therefore wield political and economic dominance in the nation, and Abu Dhabi’s oil and gas wealth has been a trump card vis-à-vis Dubai.

A construction and property bubble in Dubai burst in November 2009, shaking the region. The emirate, however, has recovered convincingly from that setback, fortified by its resilient political stability. It is posting renewed economic growth, led by the “three Ts” of transport, trade, and tourism.

In the transport sector, Dubai International Airport has become the world’s largest airport in passenger volume. It seized the top spot from London’s Heathrow Airport in 2013, with 70,480,000 passengers. Work continues on Dubai’s second international airport, Al Maktoum, which opened for operation on a single runway in 2010. When completed, Al Maktoum will be the world’s largest airport. It will have five runways and an annual capacity for 160 million passengers and 12 million tons of cargo.

Trade in Dubai includes exports of oil and natural gas, of course, and also includes a growing volume of aluminum smelted with the UAE’s abundant and low-cost electric power. Tourism is growing, too. Dubai will host the 2020 World Expo, and the organizers expect that event to draw 27 million visitors. The emirate will help accommodate them by expanding its hotel capacity from 80,000 to between 140,000 and 160,000 rooms. Another initiative that will draw tourists is Mohammed Bin Rashid City, under construction since 2012. The numerous attractions there will include the world’s largest shopping mall.

Hospitable Siting for Japanese Companies

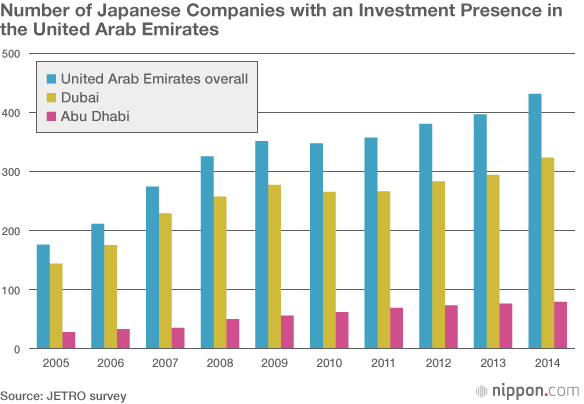

Japanese names figure prominently in the UAE’s corporate influx. JETRO reports that 431 Japanese companies had established a presence in the UAE—323 in Dubai—by the end of 2014. Enhancing the nation’s lure are its free-trade zones—known locally as “free zones”—and the recent plunge in real estate prices.

Corporate occupants of the free zones can own their businesses there outright, incur no income tax or import tariffs, bear no obligation to employ UAE nationals, and encounter no restrictions on the repatriation of earnings. Property prices, meanwhile, are one-third the level they reached during the UAE’s real estate bubble.

The UAE has 35 free zones, 25 of them in Dubai. Some 120 Japanese companies operate in the Jebel Ali Free Zone, which opened in 1985 as the UAE’s first free zone. The Dubai Airport Freezone hosts about 65 Japanese companies, and the Dubai International Financial Center free zone is home to 10 Japanese companies, including 3 megabanks.

UAE developers have built some of the nation’s free zones around distinctive themes. The developers of the Masdar City Free Zone, for example, characterize the zone as an initiative “to develop the world’s most sustainable eco-city” and to create a “greenprint” for accommodating rapid urbanization and reducing energy, water, and waste. Among the Masdar corporate residents is Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

Stubborn Concerns

Contrasting with the UAE’s powerful appeal is a pair of stubborn concerns: onerous restrictions on foreign capital outside the free zones and regional unrest. “Foreign investors cannot own more than 49% of businesses based outside the free zones,” explains a JETRO spokesperson in Dubai. “And though Dubai levies no personal or corporate income tax and does not collect social security contributions from expatriates, it does gather tax revenue through a tourism tax.”

As for violent unrest, that the UAE is arguably the safest place in the region is less than totally reassuring. A spokesperson for the Japanese embassy in Abu Dhabi notes that the nation is hardly immune to terror-related violence. The spokesperson offered three examples of the UAE’s exposure to the unrest that threatens regional stability: the perpetrators of the terrorist attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, included two UAE nationals; numerous UAE nationals have enlisted in the military force of Daesh, the self-described Islamic State; and a UAE woman inspired by IS murdered a Romanian-American woman and planted a bomb—which did not explode—in Abu Dhabi in December 2014.

(Originally written in Japanese by Harano Jōji of Nippon.com and published on June 1, 2015. Banner photo: Japan’s INPEX Corporation has secured a 5% stake in the output of the oil fields in Abu Dhabi’s ADCO Onshore Concession. Photograph courtesy of INPEX.)Middle East Dubai United Arab Emirates oil wells MENA economic diplomacy oil rights special economic zone Abu Dhabi