Kajita Takaaki Wins Physics Nobel for Work on Neutrinos

Science Technology- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On October 6, the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Kajita Takaaki of the University of Tokyo and Arthur McDonald of Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, for their discovery that the subatomic particles known as neutrinos have mass.

The announcement came a day after Ōmura Satoshi, professor emeritus at Kitasato University, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, making back-to-back prizes for Japanese researchers. Kajita, the twenty-fourth Japan-born laureate, follows the trio of Akasaki Isamu, Amano Hiroshi, and Nakamura Shūji, who won the 2014 physics prize for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes.

Revolutionary Discovery

Kajita worked as part of an international team studying neutrinos, running experiments to measure the mysterious subatomic particles at the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector in Hida, Gifu Prefecture. In 1998 he presented findings showing that atmospheric neutrinos, which normally identify as electron, muon, or tau, change their identity or “flavor” as they hurtle through space. This result was replicated by Arthur McDonald and his team at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Ontario.

These discoveries reversed previous thinking by proving that neutrinos had mass, serving as a key point in the study of particle physics, a branch of the science that seeks to understand the formation of the universe.

At a press conference following the announcement, Kajita said it was an incredible honor to share the Nobel Prize and expressed pleasure at the award shining a spotlight on pure science. Paying respect to the over 100 researchers involved in the project, the scientist stated that while it is his name on the award, the prize validates the work of each member of the Kamiokande research team.

Success for a Giant

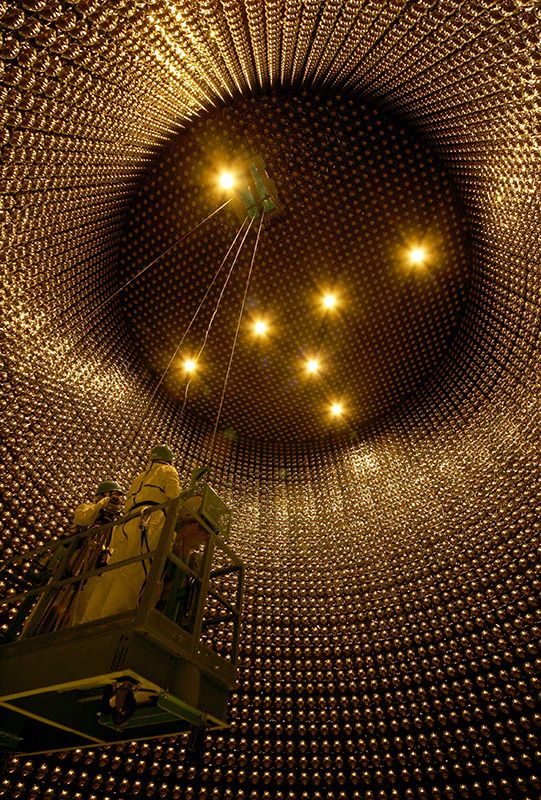

Inside of the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector. The walls of the tank are lined with receptors known as photomultiplier tubes. (© Jiji)

Inside of the Super-Kamiokande neutrino detector. The walls of the tank are lined with receptors known as photomultiplier tubes. (© Jiji)

The Super-Kamiokande facility sits 1,000 meters underground inside an old mine. Constructed by the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, it consists of a stainless steel tank roughly 40 meters high and 40 meters across filled with ultrapure water and surrounded by an array of photomultiplier tubes, which catch flashes of light produced as atomic particles pass through the liquid. The facility began operation in 1996, boasting world-leading precision. An accident in 2001 forced the neutron detector offline until repairs were finished in 2006.

The Super-Kamiokande evolved from an earlier detector, the Kamiokande used by Koshiba Masatoshi, professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, which detected neutrinos for the first time in 1987. Koshiba was awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery.

A Particle Physics Leader

Kajita was born in Higashi Matsuyama, Saitama Prefecture, in 1959. After receiving his undergraduate degree from Saitama University, he went on to earn a doctorate in physics from the University of Tokyo under the tutelage of Koshiba. He became director of the ICRR in 1999.

Kajita is the eleventh Japan-born recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics, and the seventh specializing in particle physics. The first was Yukawa Hideki in 1949, who won the prize for his theoretical prediction of mesons, particles carrying the nuclear force holding atomic nuclei together.

Along with Yukawa, Koshiba, and Kajita, other Japanese Nobel winners in the field of particle physics were Tomonaga Shin’ichirō in 1965 and Masukawa Toshihide, Kobayashi Makoto, and Nanbu Yōichirō (a US citizen at the time), who shared the prize in 2008.

(Banner photo: Kajita Takaaki at an October 6 press conference in Tokyo after the announcement of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics. © Jiji.)

science Nobel Prize physics neutrino Super-Kamiokande Kajita Takaaki