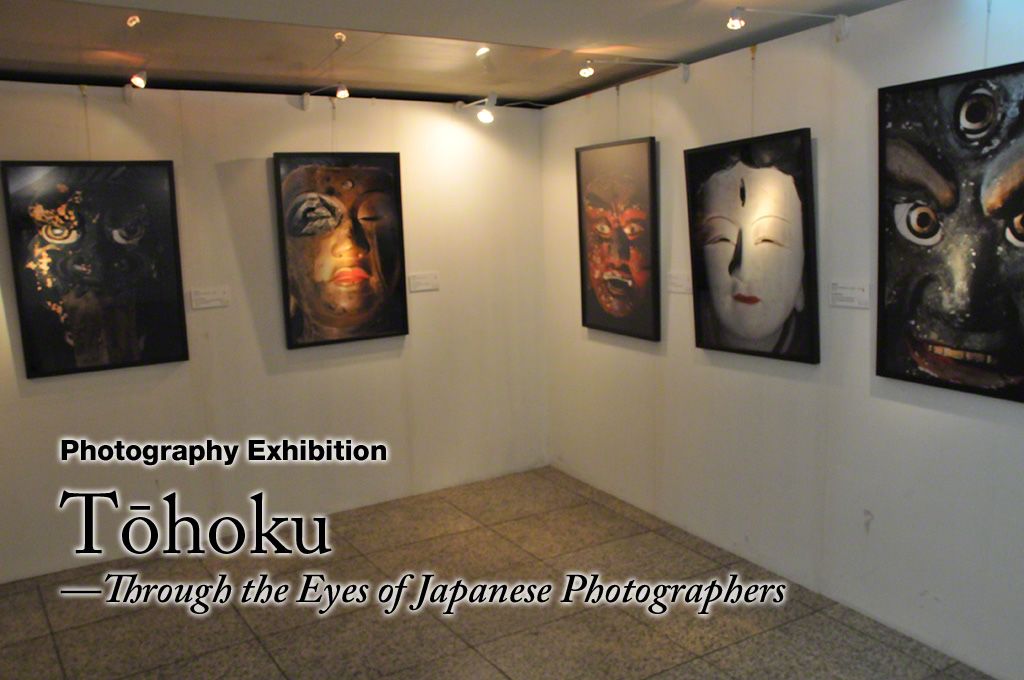

Photography Exhibition: “Tōhoku—Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers”

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Focus on the Life and Landscape of Tōhoku

A photography exhibition sponsored by the Japan Foundation, “Tōhoku—Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers,” has been touring the world since March 2012, beginning with Beijing and Rome. The exhibition, which I curated, features around 120 photographs from 19 different photographers. Together they offer a comprehensive view of Tōhoku, located in the northeast of Japan’s largest island, Honshū, chronicling the history, landscape, folk traditions, and daily life of this fascinating region.

The exhibition includes works by nine individual photographers and one photography group: Chiba Teisuke, Kojima Ichirō, Haga Hideo, Naitō Masatoshi, Ōshima Hiroshi, Lin Meiki, Tatsuki Masaru, Tsuda Nao, Hatakeyama Naoya, and the Sendai Collection. The exhibited works, which include photographs from the 1940s to the present day, cover a wide array of themes related to Tōhoku. The works of Chiba and Kojima, for instance, look at rural life back in the 1950s and 1960s, while Haga, Naitō, and Tatsuki document the festivals and religious folk rites of the region. Ōshima and Hatakeyama, for their part, combine their own personal histories with the landscapes of their hometowns, and Lin concentrates on the beauty of Tōhoku’s natural environment. There are also the photos of Tsuda, who is interested in tracing the lineage of the Japanese spirit as reflected in the relics and artifacts of the prehistoric Jōmon period. And, finally, the Sendai Collection, headed by Itō Tōru, presents a series of photographs capturing “anonymous scenes” in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture. The photographs in the exhibition vividly reveal sides to Tōhoku that most people have been unaware of up to now.

The Decision to Avoid Disaster Photos

It may not be surprising to learn that the impetus for the exhibition was the magnitude 9.0 earthquake that struck on March 11, 2011. Many parts of the Pacific coast of Tōhoku suffered unprecedented devastation from the subsequent tsunami, with the combined number of dead and missing exceeding 20,000. On top of this, many residents living near the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station had to evacuate their homes after the disaster caused from the power outage to the nuclear reactor’s cooling system. Ever since March 11, the prefectures in Tōhoku hit hardest by the natural and nuclear disaster (Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima) have been constantly in the media eye. But despite all of the detailed reporting on the disaster and the recovery effort, very little has been conveyed about the history of Tōhoku and how people live in the region.

“Tōhoku—Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers” is an attempt to bridge that gap between the out-of-the-ordinary lives of people following the earthquake and tsunami and their ordinary lives in the predisaster period. In choosing photographs for the exhibition, one obvious option would have been to include photographs taken of the devastation of the March 11 tsunami. But we made the conscious decision not to have any disaster-related photographs. The reason, as just touched on, is that such images have been prevalent in the print and Internet media. Therefore, in curating the exhibition, we concluded that there was no compelling reason to include such photographs. Another reason was that the exhibition focuses on the historical aspects of Tōhoku, which is to say, the elements that have gone into its formation.

Jōmon Traditions Live On in Tōhoku

The idea emerged that the exhibition should emphasize the importance of the remnants of Jōmon culture that still strongly tinge the spirit and cultural climate of Tōhoku. This is the culture that flourished in the period stretching from around 10,500 to 300 BC, prior to the emergence of fixed settlements among the ancient inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago. Even though this was a society of hunters and gatherers, it fostered and sustained a rich cultural spirit, as seen in the distinctive Jōmon pottery decorated with cord-shaped patterns. Tōhoku was the region of Japan where this Jōmon culture laid the deepest roots. Later Tōhoku came under the control of the central government and was seen as a backward, undeveloped area. Yet the Jōmon cultural traditions continued to live on there, finding expression in the region’s pottery and religious ceremonies and becoming a firm part of the lives of the region’s people.

The photographs in the exhibition give viewers a glimpse of the various ways in which the Jōmon spirit has manifested itself in Tōhoku. This applies not only to the folk religion ceremonies captured by Haga and Naitō but also to the photographs of everyday life by Ōshima and Hatakeyama, as well as the works of Lin and Tsuda featuring the sort of beautiful, mystical landscapes that must have been glimpsed by the ancient Jōmon people. In all of these photographs one gets a sense of vibrant traditions that live on in Tōhoku. This is an aspect of life there that I became aware of again during the process of putting together the photographs for the exhibition.

A Rich Culture Thrives on the Periphery

If you stop to think about it, the name Tōhoku—literally “east-north”—is quite suggestive. It speaks to how the region is somewhat removed from Japan’s central political and cultural life, existing on the outskirts. I would say, then, that more than just a particular region, Tōhoku represents a sort of universal concept. The “Tōhoku” for Europeans is Russia, while for Russians themselves it is Siberia. Now that the central zones of the world are becoming more homogenized in line with globalization, and all the rough edges are being smoothed out, I think that in the Tōhoku-like places on the periphery there has been a revival of the sort of rich culture that offers opportunities for interaction and integration with nature.

The exhibition is deeply moving to me personally, as a native of Miyagi Prefecture, with a family home in the Sendai district of Miyagino. I was fortunate that my mother and older sisters were not harmed by the March 11 disaster, nor did our family home suffer much damage. But it was an extremely close call, with the tsunami stretching to within just a few kilometers of the house. One of the photographers in the exhibition, Hatakeyama Naoya, lost his family home and relatives to the tsunami. Yet despite these sorts of hardships, the artists continue to take photographs and compile their work. I earnestly hope that through this work many people will be able to get a sense of the latent power of the “Tōhoku” areas that lie off the beaten track.

(Originally written in Japanese by Iizawa Kōtarō with contributions from the Japan Foundation.)

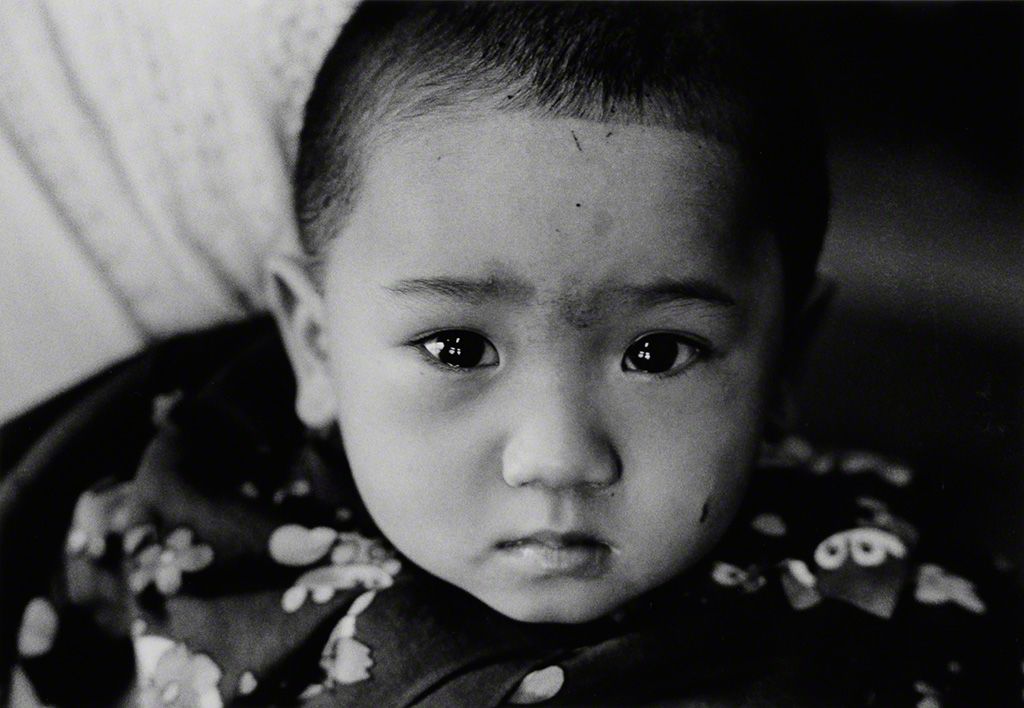

1. “Driving Off Sparrows, Kitsunezaka, Taiyū Village.” Taken by Chiba Teisuke, 1943. © Chiba Teisuke.

2. “Around Inagaki, Tsugaru-shi.” Taken by Kojima Ichirō, 1960. © Kojima Ichirō.

3. “Longevity Dance, Motsuji Temple, Hiraizumi, Iwate.” Taken by Haga Hideo, 1979. © Haga Hideo.

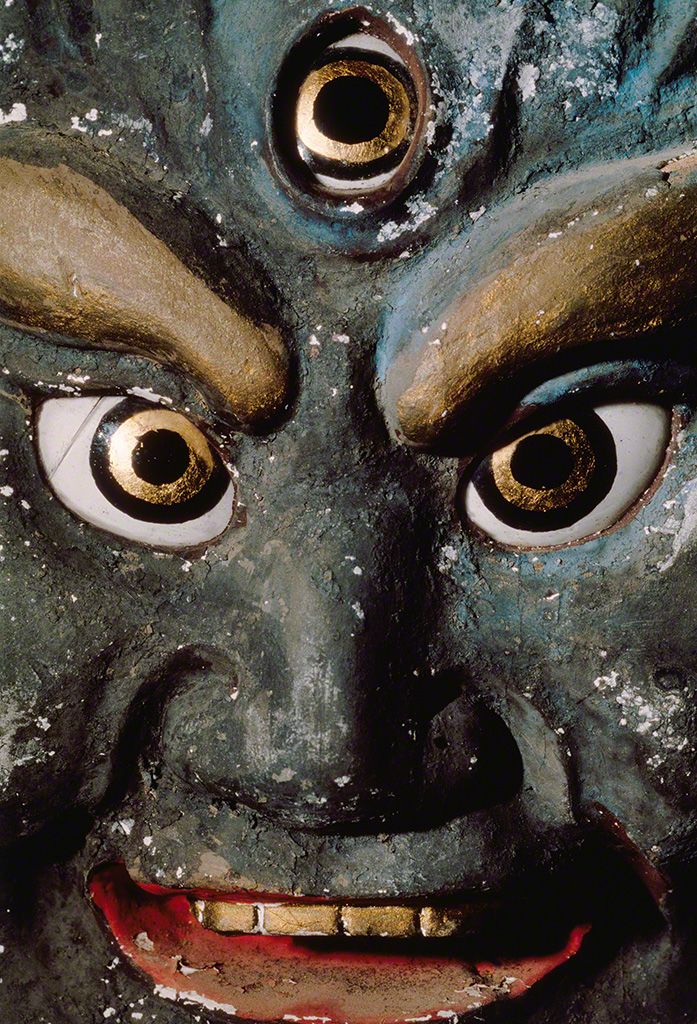

4. “Statue of Ōsawa-Butsu, Ourani Sanpō Kōjin, Dewa Sanzan.” Taken by Naitō Masatoshi, 1981–82. © Naitō Masatoshi.

5. “Ōhazama-chō, La Ville de la Chance.” Taken by Ōshima Hiroshi, 1979. © Ōshima Hiroshi.

6. “Koiwai Farm, La Ville de la Chance.” Taken by Ōshima Hiroshi, 1958. © Ōshima Hiroshi.

7. “Cherry Tree (Prunus sargentii) in the Mist.” Taken by Lin Meiki, 2011. © Lin Meiki.

8. “Reflection of Green Beech Woods.” Taken by Lin Meiki, 2011. © Lin Meiki.

9. “A Deer Shot Dead, November 2009, Kamaishi, Iwate.” Taken by Tatsuki Masaru, 2009. © Tatsuki Masaru.

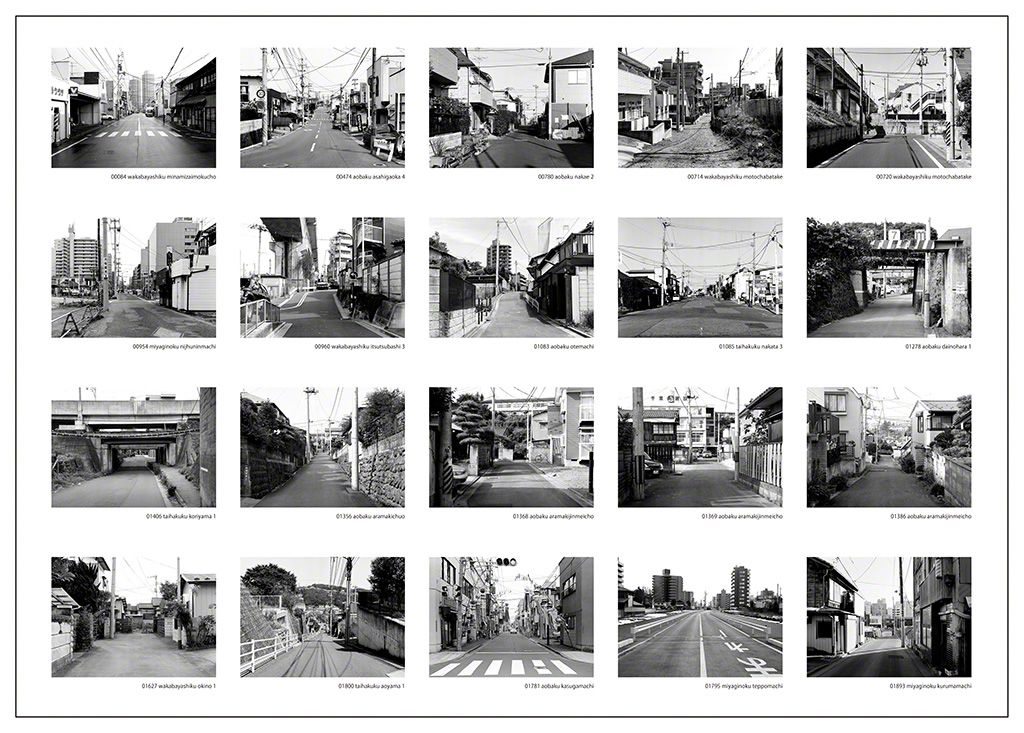

10. “Perspective, Sendai Collection Vol. 1.” Taken by Sendai Collection, 2000–3. © Sendai Collection.

11. “Kamoaosa, Akita, Field Notes (Jōmon Sites/Oga Peninsula/Yonomori).” Taken by Tsuda Nao, 2011. © Tsuda Nao.

12. “Yonomori Station, Field Notes (Jōmon Sites/Oga Peninsula/Yonomori).” Taken by Tsuda Nao, 2011. © Tsuda Nao.

13. “Kesengawa, 2003/08/23.” Taken by Hatakeyama Naoya, 2003. © Hatakeyama Naoya.

14. “Kesengawa, 2005/01/09.” Taken by Hatakeyama Naoya, 2005. © Hatakeyama Naoya.

15. “Kesengawa, 2002/08/15.” Taken by Hatakeyama Naoya, 2002. © Hatakeyama Naoya.

Great East Japan Earthquake Tōhoku Jōmon period Sendai Japan Foundation Chiba Teisuke Kojima Ichirō Haga Hideo Naitō Masatoshi Ōshima Hiroshi Lin Meiki Tsuda Nao Hatakeyama Naoya and Sendai Collection Jōmon culture Miyagino