The Birth of Culinary Experts and the Evolving Needs of Japanese Housewives

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Background to the Emergence of Culinary Experts

The profession of ryōri kenkyūka, or “culinary expert,” arose in Japan’s modern era alongside the emergence of salaried office workers. Those workers used their monthly income to support their families, while their wives became fulltime homemakers who concentrated solely on running the household. The need for culinary experts grew out of the advancement of stay-at-home wives.

The first cooking class for women in Japan was created in 1882, and the first cookbook bearing the word katei (household) in the title, indicating it was for homemakers, was published in 1903. A concerted effort around that time emphasizing cooking products and services tailored to housewives reflects the fact that up to then men had dominated the study of the culinary arts.

After the Japanese government authorized institutions of higher learning for women in 1899, the number of women who studied cookbooks and cultivated their culinary talents at schools increased. And, as more women became fulltime housewives, the genre of katei ryōri (home cooking) emerged, offering homemakers creative menu ideas.

By the 1910s, informative magazines aimed at housewives were being published in Japan, and with the birth of radio in 1927, cooking programs began to appear. Together, these trends created demand for culinary experts.

NHK’s Long-running Cooking Program on TV

The profession of culinary expert took on a higher profile in Japan after regular television broadcasting began in 1953. Cooking shows had a high level of viewership and the charismatic hosts and guests of these programs became popular figures.

NHK’s long-running cooking program Kyō no Ryōri (Today’s Dish) debuted in 1957. The show, which is still on the air, has featured a number of culinary experts over the years, such as Egami Tomi (1899-1980), popular for her motherly image; Īda Miyuki (1903–2007), whose cosmopolitan life as the wife of a Japanese diplomat gave her an air of celebrity; and Doi Masaru (1921–1995), a chef with a military background who specialized in traditional Japanese cuisine.

Egami, an influential woman whose career was at its height during Japan’s postwar period of high-speed economic growth, was one of the program’s first culinary experts. In Tsuya Akashi’s 1978 book Egami Tomi no ryōri ichiro (Egami Tomi’s Path to Cooking) Egami remarked that “the efforts of housewives to surprise family members with new, delicious recipes brings harmony to the household and also passes along those flavors to the next generation.” She also said that the efforts of housewives to support a household lead to social stability. Underlying this comment was Egami’s own background as well as the social situation in Japan at the time.

The Postwar Dream of Having a Nuclear Family

Egami was born into a family of wealthy landowners in Kumamoto Prefecture. Her mother was in charge of directing the servants in the kitchen, and passed along to her daughter the idea that women were most attractive when working energetically in the kitchen. Egami married an army engineer. She accompanied him when he was transferred to France in 1927. While there she enrolled in the famous Le Cordon Bleu culinary school in Paris to study French cuisine. Upon returning to Japan she opened her own culinary school, urged on by friends she had met in Paris. After the end of the war she focused her energy on running this school. The school, which had been based in Fukuoka, was moved to Tokyo, and in the years that followed it was often showcased in the media. At its height, around 6,500 students were enrolled.

The period of postwar economic growth coincided with a rapid expansion in the number of salaried workers in Japan. In marrying these “salarymen,” it became possible for women to achieve the dream of building a nuclear family. The division of labor within these nuclear families—where men worked outside and women stayed home to maintain the household and raise children—signified an advancement in the position of women in Japan.

It is not surprising that women embraced their new matriarchal roles, considering that up to then they had been treated as marginal workers who not only had to toil for long hours doing domestic chores but also were tasked with agricultural or commercial work. These women were treated almost as slaves in cases where they were living together with their husbands’ parents.

Japanese Kitchens Get a Makeover

The new Japanese Constitution enacted in 1946 marked a step forward for the position of women in Japan by proclaiming gender equality. The generation of women that were able to receive an education under the new Constitution came of age at the peak of postwar economic growth. Many of the men who became salarymen during this period were second or third sons from the countryside who did not have the responsibility of caring for their parents. The new generation of housewives became equal partners with their husbands in carrying out their respective tasks.

Japan’s rapid economic growth also led to major changes in the kitchen. The spread of plumbing and gas meant that it was no longer necessary to draw water from a well or build fires. Earthen floors were replaced with wood, making it easier to look after a kitchen. Later, the expansion of power plants made electricity widely available, leading in turn to a rapid increase in household appliances. Refrigerators allowed housewives to keep ingredients fresh without having to go shopping as often, while rice cookers made it possible to automatically cook a perfect batch of rice each time. During this period, washing machines and televisions also spread throughout Japan.

Food distribution also improved, making it possible to purchase a wider range of ingredients at supermarkets, including a greater array of fresh fish and vegetables. The government encouraged citizens to consume more protein, and also promoted increased production of livestock and dairy items. During this period, Japanese people began to widely consume milk, eggs, and meat in their daily lives.

Culinary experts offered advice suited to Japan’s increasingly modern kitchens, such as how to adjust Western and Chinese cuisine to suit Japanese tastes. Preparing these new dishes was often an intricate affair, but housewives eagerly added these recipes to their repertoire.

These housewives were of a generation raised during the turbulent wartime and immediate postwar period, when Japan faced severe food shortages, and had not been taught how to cook as girls. And many of them had to move from the countryside to the city as teenagers, depriving them of the chance to learn from their parents. These factors contributed to the need for culinary experts in Japan.

Balancing Jobs and Housework

Not long after this emergence of the postwar housewife, more and more women began to enter the workforce. The global feminist movement also began to gain momentum from the 1970s, eventually leading to Japan passing the Equal Employment Opportunity Law in 1986. During this period, a series of oil crises and other factors led to a decrease in men’s salaries, making it increasingly necessary for married women to work. But many of these housewives were forced to take low-paying part-time jobs.

Despite more women entering the workforce, the low social status of women saw them continuing to shoulder the burden of performing housework. This meant they were expected to do the shopping, cooking, and cleaning, while working a job at the same time.

Husbands tended to view housework as a job for their wives, and as men were often tied down to jobs demanding long hours, it is unlikely their schedules would have allowed for housework even if they had wanted to. By this time, ready-made meals and take-out food became widely available, but social expectations often meant women felt guilty about taking advantage of such options.

A Culinary Expert for Busy Times: Kobayashi Katsuyo

This period saw the emergence of Kobayashi Katsuyo (1937-2014), a culinary expert who created a sensation by offering recipes and techniques that greatly simplified the cooking process.

Kobayashi was born into a family of Osaka merchants. Her mother loved to cook and her father was a food lover who also liked to dabble in the kitchen. Although Kobayashi had a refined palate, she did not know how to cook at the time she got married, and the first meal she prepared was a disaster. This setback spurred her to begin learning more about the culinary arts, picking up tips from her mother and from the shop owners where she purchased fish and other ingredients. The distinctive way she set about teaching herself how to cook became one of her strengths.

Kobayashi became a professional culinary expert after suggesting that a TV variety show add a cooking segment to enliven the program. The show’s producer responded by asking Kobayashi to do the segment herself. For the show, she ended up cooking some dishes in the studio that she had learned from various shops and restaurants.

As her on-air experience grew, Kobayashi became a TV celebrity. And as she became increasingly busy, she began to present ideas for simple recipes. This struck a chord among TV viewers, boosting her popularity even more.

A Role Model for the Modern Housewife: Kurihara Harumi

Another generational change occurred when children raised amid Japan’s newly-garnered prosperity became adults. The members of this generation learned how to cook from mothers who had broad repertoires and customarily prepared two or three different dishes a day. Japan’s restaurant industry was expanding during this time and this group also developed their palates through familiarity with professionally prepared cuisine.

One culinary expert who has responded to the needs of this new generation is Kurihara Harumi (b. 1947). She has earned widespread popularity by coming up with new ways to tweak recipes by adjusting ingredients and seasoning, and by offering ideas on how to improve everyday dishes and create dishes that women want to make for themselves. In showcasing her lifestyle as a content housewife, Kurihara has also inspired many women to become culinary experts.

In the new century, as take-out and restaurant food improves and grows in demand, the number of women who find it hard to match that level—and give up cooking as a result—is on the rise. Women have also become busier as their social status increases, leaving them little time to cook. They have become a part of the corporate world, where long working hours are expected of them. Now that working women outnumber housewives, purchasing prepared meals is becoming more common.

Yet, at the same time, there are and increasing number of culinary experts, and a huge array of cookbooks available, offering every sort of recipe imaginable. This seems to offer some hope that even as more people buy meals outside the home, there are still many who are interested in preparing meals by themselves.

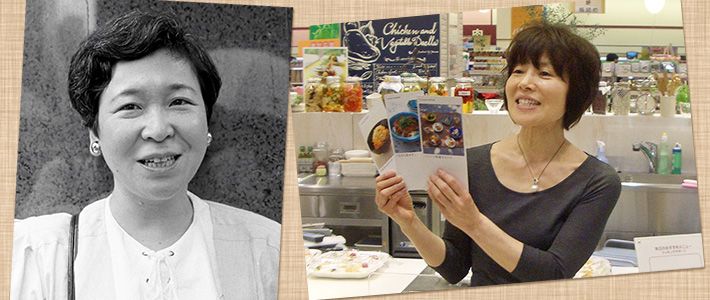

(Original Japanese article published on October 9, 2015; banner photographs are of Kobayashi Katsuyo, on the left, and Kurihara Harumi, taken in 1985 and 2008, respectively. © Jiji Press)▼Further reading

postwar family household constitution NHK women Cooking Equal Employment Opportunity Law Washoku Harumi Kurihara culinary

Traditional Japanese Cooking in the Home: An Endangered Art

Traditional Japanese Cooking in the Home: An Endangered Art