The Question of Imperial Abdication

The Historical Background of How Japan Chooses Its Era Names

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Gengō: The System of Era Names

The prospect of Emperor Akihito’s abdication has drawn attention to the question of what era name (gengō, also called nengō) will be chosen to replace the current one, Heisei, when his successor takes the throne. It is reported that a number of proposals have already been advanced.

Even today, the use of calendars based on non-Western eras like Japan’s is far from uncommon. The Islamic calendar is widely used in the Muslim world, and in Thailand years are officially numbered according to the Buddhist era. Taiwan numbers years according to the Minguo (Republic) era, counting from 1912, the year of the founding of the Republic of China, while North Korea has its own era, Juche, used alongside the Western era, also counting from 1912, the year of its first leader Kim Il-sung’s birth. In East Asia, countries that were vassals of China traditionally used Chinese era names to number their years, and if a country used its own year-numbering system, that indicated its non-vassal status. There were also cases where countries followed the Chinese system for external purposes but used their own calendars domestically.

In premodern Japan a new era name was sometimes adopted to mark the accession of a new emperor, but it was also common to change the gengō on other occasions, such as in the wake of a natural disaster. A single era could include parts of the reigns of two emperors, such as the Keiō era, which started in 1865 under Emperor Kōmei and ended in 1868, during the reign of Emperor Meiji. Under the current system, adopted in 1889, the gengō is changed only when a new emperor takes the throne. The following table, which gives the eras and reigning emperor’s names since 1848, shows the contrast between the two systems.

Era Names and Reigning Emperors Since 1848

| Era name | Years | Emperor(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Kaei | 1848–1855 | Kōmei |

| Ansei | 1855–1860 | Kōmei |

| Man’en | 1860–1861 | Kōmei |

| Bunkyū | 1861–1864 | Kōmei |

| Genji | 1864–1865 | Kōmei |

| Keiō | 1865–1868 | Kōmei, Meiji |

| Meiji | 1868–1912 | Meiji |

| Taishō | 1912–1926 | Taishō |

| Shōwa | 1926–1989 | Shōwa |

| Heisei | 1989– | Akihito |

Note: Under the current system, emperors are posthumously named after their eras. For example, the current emperor’s father and predecessor, known in English as Emperor Hirohito during his reign, is now called Emperor Shōwa. In Japanese, the emperor’s personal name is not used even during his reign; instead, he is referred to as Tennō Heika (His Majesty the Emperor) or Kinjō Tennō (the current emperor).

The adoption of the system of one era name per reign, identifying the era with the emperor, is seen by some as an expression of the emperor’s control over time itself.(*1) The system provided for the emperor to decide on the name of the era and for the era to end upon his death. The era name came to serve as a symbol of the times, a sentiment expressed, for example, in Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro.

After Japan’s defeat in World War II and the adoption of the new Constitution of Japan, the Imperial House Law was also revised, and there ceased to be a solid legal foundation for the gengō system. The era name Shōwa continued to be used on a customary basis, but calls for abolition of the system were often heard. It was only in 1976 that Shōwa regained its legal standing with the enactment of the Era Name Law; this was followed by the adoption of official guidelines specifying the procedures to be followed in selecting a new era name.

After Emperor Shōwa passed away in January 1989, bringing the Shōwa era to an end, the current era name, Heisei, was adopted according to these postwar democratic provisions, with the decision being made not by the emperor but by the cabinet.(*2)

If and when Emperor Akihito abdicates, as he has suggested that he wishes to do, a new era name will be adopted. In what follows, I would like to explain how the gengō system has changed and how the changes have been discussed and to introduce the procedures that will be used in deciding on the era name to follow Heisei.

Adoption of the “One Reign, One Era Name” Practice

It was during the reign of Emperor Meiji (1867–1912) that the government adopted the current “one reign, one era name” practice, meaning that a new era name is adopted when—and only when—a new emperor takes the throne. This is the system that was then being used in China under the Qing Dynasty. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when the shogunate was abolished and imperial rule restored (and the era name was changed to Meiji), the government undertook to modernize Japan. People think of this as having involved Westernization, which it did in many ways, but in some respects it involved adopting systems from Qing China, Japan’s great neighbor on the Asian continent. Another practice based on the Qing model was the compilation of the annals of each emperor. Such documents had also been put together in Japan before that time, but during the Meiji era the Ministry of the Imperial Household compiled the chronicle of Emperor Kōmei’s reign, and the practice has continued for subsequent reigns through that of Emperor Shōwa.

At the start of Japan’s Meiji era, the era name in Qing China was Tongzhi. This was followed by the Guangxu and Xuantong eras, each corresponding to a single imperial reign. In 1912, which brought the start of the Taishō era in Japan, the Qing Dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution, and the Republic of China was established. A new era name, Minguo (meaning “republic”), was adopted, and since there were no longer emperors or reigns, it continued to be used unchanged, regardless of changes of president. The era was briefly interrupted in December 1915 when President Yuan Shikai declared himself emperor, adopting the era name Hongzian, but his imperial rule lasted only three months before the republic was restored, along with the era name Minguo. This name is still used in Taiwan, where 2017 is Minguo 106.

Modifications over the Years

The “one reign, one era name” gengō system was one of the provisions of the Imperial House Law that was adopted along with the Constitution of the Empire of Japan (commonly known as the Meiji Constitution) in 1889. But the system was originally adopted under a government ordinance at the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The system was modified in 1909 under the Regulations Governing the Accession to the Throne, which made it explicit that the era name was to be changed immediately after the death of an emperor, that the new era name was to be determined by imperial decision, and that it was to be announced by imperial rescript. At least in procedural terms, the emperor himself chose the era name and announced it in an imperial rescript. I might note that the system was not exactly the same as the one used in Qing China, where the new era did not start until the year following the previous emperor’s death.

With Japan’s defeat in World War II, the existing Imperial House Law was abrogated, and a new one was adopted in 1947 under the postwar Constitution of Japan. But the new Imperial House Law contained no provisions concerning the era name. In the early postwar period, some questioned the need for the monarchy, and there were calls for Emperor Shōwa to abdicate; in addition, some called for abolition of the system of era names. For example, in 1950 the Science Council of Japan submitted a proposal to the prime minister, speaker of the House of Representatives, and president of the House of Councillors for adoption of the Western system of numbering years in place of the era name system.(*3) The Science Council asserted that era names had no scientific meaning and no basis in law, and that they were ill suited to a democracy inasmuch as they were intrinsically linked to the prewar system of imperial sovereignty. That same year a bill for abolition of era names was deliberated in a House of Councillors committee, and the topic seems to have been the object of a certain amount of public debate.

In January 1977, the Japan Socialist Party began to prepare a bill on abolition of the gengō system. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party undertook countermoves,(*4) and these led to the passage of the Era Name Law in June 1979 and the adoption of guidelines on the procedures for selection of the era name in October of the same year. The Era Name Law is Japan’s shortest law, consisting of just two sentences: “1. The era name shall be determined by cabinet ordinance. 2. The era name shall be changed only in the case of a succession to the imperial throne.”

The Process of Selecting a New Era Name

The process of selecting a new era name to replace Heisei will be conducted basically according to the same procedures followed for the change from Shōwa to Heisei in 1989. The Era Name Law calls for the new era name to be determined by cabinet ordinance; the details are set forth in the aforesaid guidelines on the procedures for selection of the era name as follows:(*5)

1. Consideration of prospective names

(1) The prime minister shall select persons of high discernment and charge them with proposing appropriate prospective names for the new era. (2) Several people shall be so charged. (3) The prime minister shall request each proposer to present two or three prospective names. (4) The proposers will accompany the presentation of their prospective names with an explanation, including the name’s meaning and source.2. Screening the prospective names

(1) The director general of the Prime Minister’s Office shall consider and screen the prospective names presented by the proposers and report the results to the prime minister. (2) In considering and screening the prospective names, the director general of the Prime Minister’s Office shall bear in mind the following criteria: The name is to be (a) one whose meaning is appropriate to the ideals of the nation, (b) two kanji, (c) easy to write, (d) easy to read, (e) one that has not previously been used as an era name or emperor’s posthumous name, and (f) not in common use.3. Selection of draft proposals

(1) At the prime minister’s direction, the chief cabinet secretary, director general of the Prime Minister’s Office, and director general of the cabinet legislation bureau shall meet to scrutinize the prospective names as screened by the director general of the Prime Minister’s Office and shall select several of them as draft proposals. (2) The draft proposals shall be discussed at plenary ministerial conference. Also, the prime minister shall contact the speaker and deputy speaker of the House of Representatives and the president and vice-president of the House of Councillors and ask their opinions concerning the draft proposals.4. Decision on the new era name

The cabinet will adopt an ordinance on the new era name.

The post of director general of the Prime Minister’s Office no longer exists, and so it is not clear who in the Cabinet Office will be responsible, but the new era name will probably be selected in accordance with the above procedures. Unlike when the Meiji Constitution was in effect, there is no occasion for taking the emperor’s will into account.

Abdication and the Era Name

If and when the current emperor abdicates, this will modify the principle that the era name changes only at the death of an emperor. It will be a departure from previous practice, but not a major one, inasmuch as a new era name will be adopted as a new emperor takes the throne. Abdication will require the creation of new arrangements, but the change of era name will not.

It has been reported that a number of prospective era names have already been proposed.(*6) In other words, it seems that the first step of the process set forth above is underway. The current era name, Heisei, was based on passages in two Chinese classics, the Shiji, or Records of the Grand Historian, and Shujing, or Book of Documents. The new era name is likely again to be a two-kanji compound from classical Chinese works. And persons currently involved in the selection process are thus likely to include researchers in the fields of Chinese philosophy and Eastern history and scholars of classical Chinese. However, since there is no rule requiring the era name to be taken from the Chinese classics, it is not certain that the new era name will be from such a source.

A century and a half have passed since the beginning of the Meiji era, when Japan adopted the Chinese practice of one era name per reign. Now we face many issues and possible changes with respect to the Japanese monarchy, including the question of whether to produce an imperial chronicle covering the reign of the current emperor. The change of era names may offer a good opportunity for reconsidering such existing arrangements.

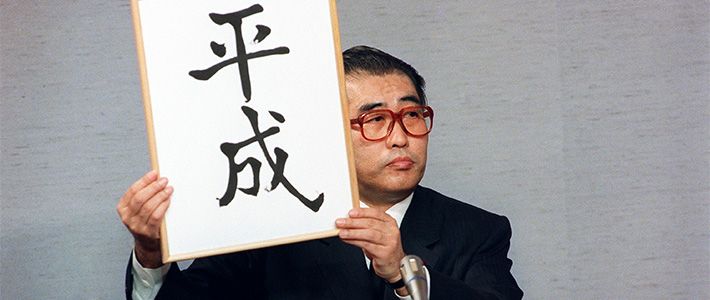

(Originally published in Japanese on April 27, 2017. Banner photo: Chief Cabinet Secretary Obuchi Keizō announces the adoption of the era name Heisei on January 7, 1989. © Jiji.)

(*1) ^ Hara Takeshi, “Senchūki no ‘jikan shihai” (“’Temporal Control’ During the War Years), in Kashika sareta teikoku—kindai Nihon no gyōkōkei (The Empire Made Visible: Imperial Visits in Modern Japan) (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 2011).

(*2) ^ Suzuki Hirohito, “Kaigen o tōshite mita tennō: “Shōwa” kaigen to “Heisei” kaigen no hikaku bunseki” (The Emperor Viewed Through the Change of Era Names: A Comparative Analysis of the Change to Shōwa and to Heisei), Nihon Kenkyū, International Research Center for Japanese Studies, no. 54 (January 2017). I referred extensively to Suzuki’s article in writing this piece.

(*3) ^ Japanese text at http://www.scj.go.jp/ja/info/kohyo/01/01-57-m.pdf, accessed March 23, 2017.

(*4) ^ In the House of Councillors on December 20, 1977, Horie Masao of the LDP raised a question regarding the era name system. He cited the opinion advanced by constitutional scholar Minobe Tatsukichi that, even without explicit mention of the era name system in the current Imperial House Law, the system still had a legal basis dating back to the official adoption of the “one reign, one era name” practice in 1868. Horie asked if the government accepted this opinion—and if not, on what basis it placed the era name system. The government replied that it did not go along with Minobe’s opinion but that it woud carefully deliberate the subject, paying close attention to trends in public opinion.

(*5) ^ Japanese text at https://www.digital.archives.go.jp/das/image/M0000000000001159113, accessed March 25, 2017.

(*6) ^ Mainichi Shimbun, April 7, 2017.