Solitary Spaces: Dioramas of Unattended Deaths Bring “Kodokushi” Phenomenon into Perspective

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nearer than You Think

Disturbing stories of individuals who die alone in their homes and go unnoticed for days or weeks have become all too common in Japan. Even as accounts of kodokushi, as the phenomenon is known, appear on television and in print with increasing regularity, the public has yet to look past the macabre details and acknowledge social isolation as an issue of pressing concern to their own communities.

There are an estimated 30,000 cases of unattended deaths in Japan each year, but only since around 2019 has the issue of kodokushi come to be widely recognized. Back in 2014 when I started at To-Do Company, a firm that specializes in cleaning homes where residents have died—sometimes called “trauma cleaning”—few people knew what the term meant, and even fewer were aware of my line of work.

When an individual dies alone at home, my colleagues and I clean out the room and make it habitable again. This involves collecting any articles left behind by the deceased person, removing trash and any biological materials, eliminating stains and odors, and disinfecting the space. Residences are often in a shocking state of disarray, but we take special care to gather and comb through the resident’s belongings, sorting out personal effects—particularly items with monetary and sentimental value—and passing these on to surviving family members.

Our job also involves helping the bereaved family through the emotional effects of kodokushi, including listening to their stories of their loved one and providing words of support. To honor the deceased, we place offerings of flowers and incense at the site and offer up prayers for the soul of the departed.

Miniature Narratives

As a specialized field requiring a great deal of sensitivity and discretion, trauma cleaning is little understood. Seeing a need to increase awareness of our sector of the industry and draw attention to the issue of unattended deaths, in 2015 my company set up a booth at the funeral trade show Endex Japan. I helped run the exhibit, which was an eye-opening experience. I tried to impress on visitors the direness of the situation by pointing out the ongoing rise in cases of kodokushi, stressing that no one was immune to the risk. To my surprise, many of the people I spoke with, both individuals in the funeral business and members of the general public, openly scoffed at the idea. They refuted the possibility that in a country like Japan a person’s death would go unnoticed for days, weeks, or months, and asserted confidently that they would never suffer such a lonely fate.

Kojima’s diorama titled “Kodokushi with Several Pet Cats Left Behind.” One of the animals survived and was found in the back room.

Having dealt with the aftermath of kodokushi firsthand, listening to these responses left me speechless. It occurred to me, though, that the former residents of the apartments I had cleaned had probably shared similar views. They never imagined that they would die alone, their bodies lying undiscovered. This made me realize that I needed a different approach if I wanted to get my message across, something that would convey the stark reality of unattended death in a way the public could better understand. Pondering the problem, I struck upon the idea of creating miniature models of kodokushi pieced together from my experiences. By combining shared aspects—my works are composites, not specific scenes—I could document the haunting, solitary atmosphere of these spaces while also preserving the dignity and privacy of the deceased and their families. This was how I began creating dioramas of kodokushi.

“Following a Young Person’s Suicide by Hanging.” The resident of this apartment left a final message, the word gomen (sorry), written on the wall with tape.

Having never made a diorama before, I taught myself the craft through a combination of watching videos online and trial and error. I gradually learned how to construct the frames of the rooms, as well as different furniture items, and tricks like applying eyeshadow to mimic the dust and grime of lived-in spaces. I bought whatever paints, tools, and other materials I needed and set about reconstructing detailed miniature scenes of kodokushi, one story at a time.

Rather than adhere to the traditional 1:12 scale of many miniature creations, Kojima varies the size of her dioramas.

Scenes of Isolation

I want to talk specifically about three diorama I created. The first, “Kodokushi, Age 50–60,” depicts the unattended death of an individual and carries the theme of “staying connected.” This age group accounts for a significant portion of kodokushi cases, particularly those that go undiscovered for long periods. A common contributing factor in cases is a lapse in communication with family, neighbors, and others in society.

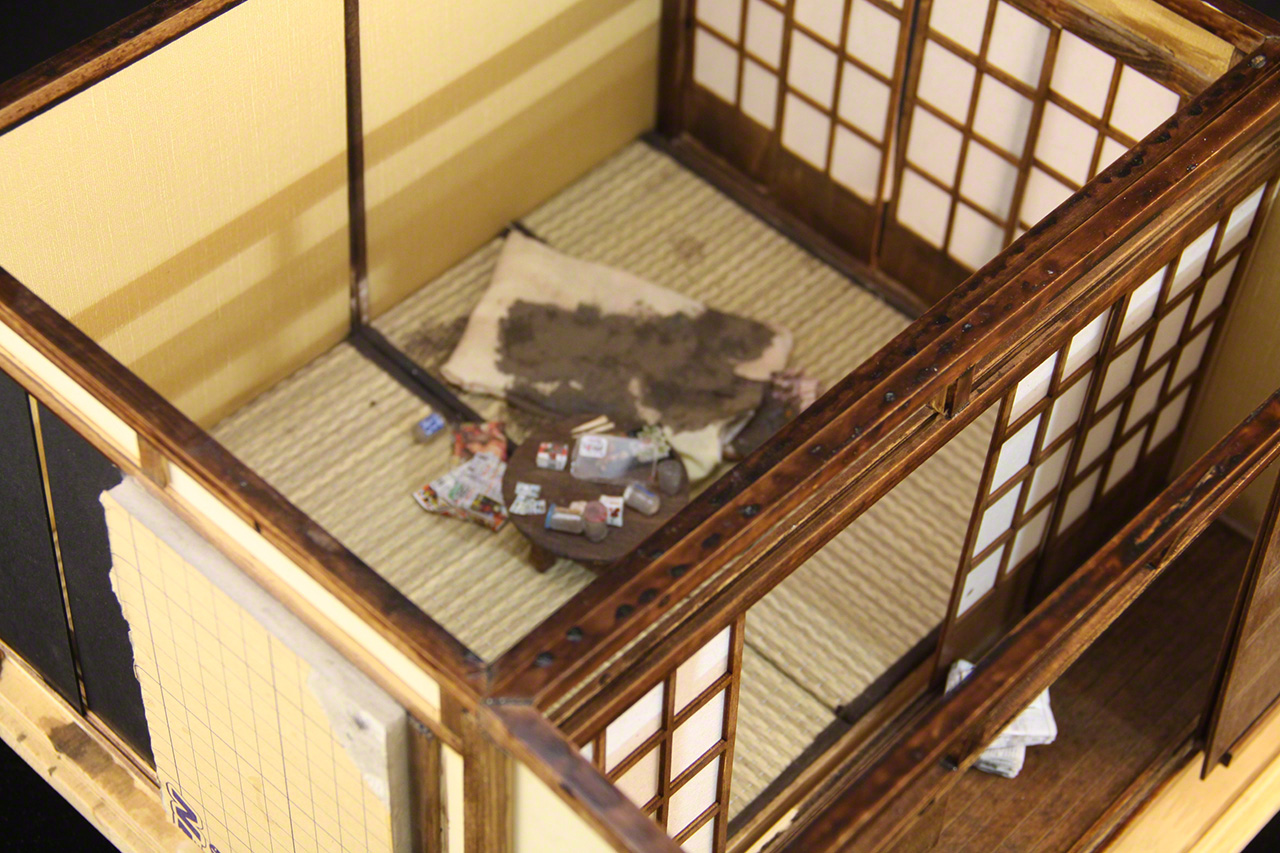

Kojima’s first diorama, “Kodokushi, Age 50–60,” tells the story of a person who has few social interactions.

In this closeup scene, empty containers, food packaging, and other trash litter the table and floor next to a stained mattress.

The individual was not of particularly advanced age, and may not have felt compelled to check in regularly with family and friends—who in turn, not wanting to impose, might similarly have assumed that the person was healthy and doing fine. They often remained to themselves, even ignoring the door when visitors came knocking, and consequently neighbors took little notice of their extended absence, delaying discovery. In some cases, close to half a year can pass before a body is found.

I hope those who view the diorama come away with a better appreciation for the importance of little interactions in life like phone calls, visits, neighborly greetings, and other forms of day-to-day communication.

The second diorama is “Kodokushi Caused by Heat Shock.” During the cold of winter, a person stepping from a heated room into an unheated area, such as a hallway, toilet, or bath, will experience a rapid spike in blood pressure as their blood vessels constrict in response to the frigid air. Stepping into a steaming bath will alleviate the chill, but sudden swings in blood pressure caused by these dramatic temperature changes can trigger a heart attack, stroke, or other medical condition. I have cleaned numerous apartments where the inhabitant drowned in the bathtub or collapsed while on the toilet as a result of heat shock.

“Kodokushi Caused by Heat Shock” depicts the bathtub where the victim was discovered.

Taking simple measures like putting on a pair of slippers to guard feet against cold hallway flooring, warming the toilet and the bath’s changing space with small heaters, and running the shower before stepping into the bathing area can help guard against heat shock. It is also a good idea to keep the bathwater moderately warm, no more than 40 degrees Celsius, and to install a heated toilet seat or buy a warmer cover. Such minor precautions can be life saving.

The third diorama is “Kodokushi in a Compulsive Hoarder’s Room.” Many people look on the bulging bags of garbage, discarded boxes, and other trash with shock, assuring themselves that they would never succumb to such a state of filth. But the scene conveys a different message. The person who lived here might not have been untidy by nature. However, some tragedy in their life—a divorce or failed relationship, the loss of a job, bullying, overwork, the death of a loved one or pet—or the onset of mental illness zapped them of their will to stay ahead of the clutter. I want viewers to realize that anyone, given the right circumstances, can unexpectedly find themselves in the same situation.

Kojima poses with “Kodokushi in a Compulsive Hoarder’s Room.”

Making Sense of Kodokushi

My work has changed since the onset of the pandemic. Factors like companies switching to remote work and the growing number of shuttered businesses have meant that for better or worse, people are spending more time at home. Subsequently, requests to clean out belongings from homes have decreased, as relatives of a deceased person now have more time to take care of such matters on their own. Conversely, there has been an increase in demand for trauma cleaning, particularly cases of kodokushi where the cause of death is unknown.

This has further impressed on me the fact that death is capricious. None of us can say when or how the end will come. A person might feel assured that their husband, wife, or children will be by their side when the time comes, but there is no guarantee how life will play out. Certainly, many of the deceased whose homes I clean were living alone, but this does not mean they were unmarried or that they had no children, but for whatever reason wound up dying alone.

“Kodokushi of an Elderly Person Living a Comfortable Life” shows yet another perspective on a solitary person’s final time.

An outsider might be inclined to harshly judge the relatives of a person whose death went unnoticed, accusing them of turning their backs on the individual and condemning them to die alone. But this assumes that kodokushi is inherently bad, which is not the case. We often hear of people wanting to die at home in familiar surroundings. Why is kodokushi not seen as fulfilling this wish?

Part of the problem lies in the word we use to define unattended death. Kodoku implies isolation and loneliness, but only a handful of individuals who die alone at home are truly isolated from society. Most enjoyed vibrant relationships with friends and family right up to the very end. They took trips, shared hobbies, played with their grandchildren, and in other ways led rich, fulfilling lives. It strikes me as unfair to label their passing as a “lonely death” when they were anything but alone. A different term like jitakushi (death at home) might be more suitable, helping the public see the issue of unattended death in a different light.

There are reasons to be hopeful that the situation is changing. Increased media attention has boosted awareness of the issue, particularly among people who know someone who is at risk. Consequently, bodies are being discovered earlier than before, lessening much of the trauma of kodokushi.

Kojima’s “Heat Shock Kodokushi on the Toilet” conveys to viewers the deadly danger of this phenomenon.

I hope this article compels readers to reach out to those they love. It is easy to find excuses to put things off, but the opportunity will not always be there, and may disappear sooner than you think. Similarly, I want my creations to inspire people to appreciate the importance of living life to its fullest. Death comes to us all at some point. As I carry out my trauma cleaning work each day, I hope with all my heart that none of us plod along under the burden of regrets, but rather treasure each day.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: “A Kodokushi Leaving Many Mementos to Deal With,” a diorama showing a cluttered room. All photos © Kojima Miyu.)