Why Society Will be the Real Loser from China’s Low Birth Rate

World Society Economy Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Fatal Policy Blunder

In May, China’s National Bureau of Statistics released the results of the 2020 census. According to the Bureau, China’s population is now 1,411,780,000—a rise of 11,730,000 from the 1,400,050,000 sampling estimate published in 2019. However, the number of children aged 14 and under reported in the census (253,380,000) was 14,730,000 more than the total number of births announced over the last 15 years, the result of children that were missed in annual sampling being picked up by the census, carried out once a decade. It is said that parents who kept their children hidden out of fear of being sanctioned for “surplus births” have now stopped doing so in the wake of the recent relaxation of sanctions.

Since the beginning of this century, the view that the decline in China’s birth rate is accelerating has become more prevalent, but the government long refused to change course, instead insisting that the country had a fertility rate—the average number of children born to each woman of childbearing age—of at least 1.8. One reason for the government’s refusal to make corrections to its policy was the rigid pyramid formed by the family planning division that oversaw the one-child policy, topped by members of the central National Health and Family Planning Commission and having the agricultural villages and urban subdistricts that formed the base of the Communist Party’s organization and administrative apparatus at its base. This pyramid had a vested interest in the fines levied on surplus births. Because these fines were indispensable as a source of income for maintaining the party and its administrative structure, particularly in poor villages, the abolition of the one-child policy would have made it difficult to maintain the grassroots organization that monitored trends among rank-and-file citizens.

Another reason for the lack of change was the tendency to see any debate on the fate of the single-child policy as taboo. While the reasons for this within the Chinese Communist Party are not clear, Chen Yun and other members of the Party’s conservative faction were said to have been very concerned by the population explosion seen in agricultural areas in the 1960s. The fact that the one-child policy was devised by leaders who acted out of fear might be one reason that debate on the policy was seen as taboo.

It was China’s last census, carried out in 2010, that caused the government to change tack. Concerned at the direction demographics were taking, the National Bureau of Statistics embarked upon an organization-wide investigation, in July 2012 releasing full birth and death statistics by year, municipality, and rural district.

The 1.18 fertility rate figure that was announced shocked the CCP, leading the government to finally change tack and proclaim a universal two-child policy in its thirteenth Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development announced in 2015, far too late. Rather than being punished, however, the National Health and Family Planning Commission that had for many years led the country down the wrong path was absorbed into other government offices, with “Family Planning” erased from its title.

Effects of Relaxation Short-Lived

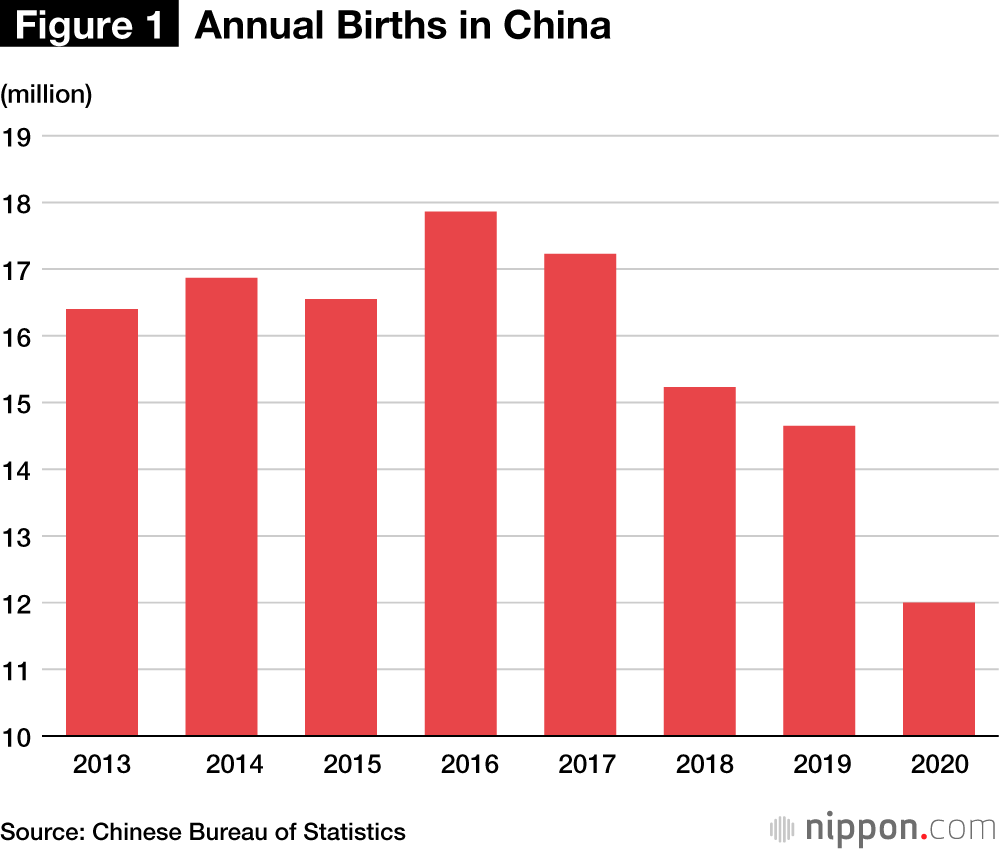

Most noticeable in the latest census was the fact even according to census figures, which have a higher capture rate, the number of births is still rapidly declining, as shown in Figure 1. Experts attribute the decline to the waning of the effects of the 2015 relaxation of the one child policy. The unnatural phenomenon seen in 2019, when there were fewer first-borns than second- and third-borns, suggests the birth rate only rose momentarily when restrictions were relaxed.

While the total fertility rate derived from the 2020 census results was 1.3, some experts believe that after adjusting for the transient effects of the relaxation of restrictions, the net rate is actually around 1.1, according to the economist and demographic researcher James Liang Jianzhang.

In future, the rapid decline in the number of women of childbearing age will further exacerbate this decline in births. From 2017 to 2030, the size of the female population aged 20–35 will shrink by 31%, and the number of women aged 25–30 will fall by a whopping 44%. When you also take into account the recent marked trend to pursue higher education, and the fact that urbanization is making couples get married and have children later, you can see that there is a significant possibility that the fertility rate will decline even faster than the number of women of childbearing age.

It follows that it is now too late for China to escape from this ultralow structural fertility rate. The focus is now on how the country will adapt to this future.

Avoiding Economic Impact

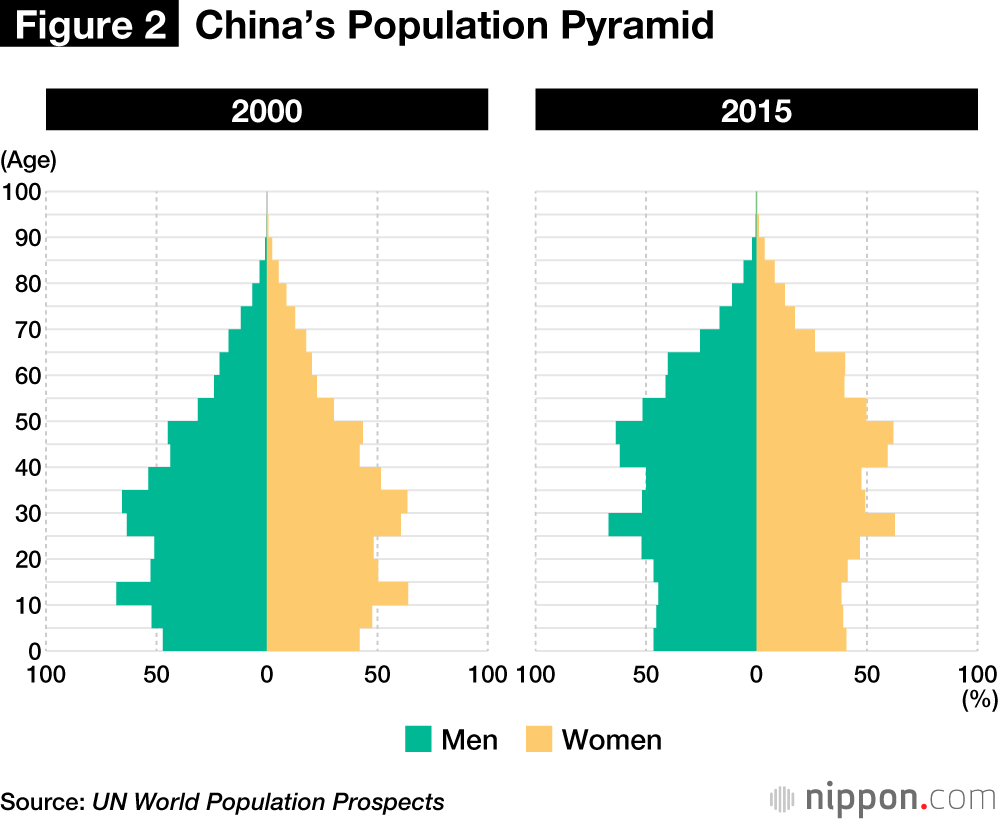

In regard to the future of China’s population problem, the world is most interested in what kind of impact demographics will have on the economy. It is a well-known fact that China’s past economic growth was supported by its “population bonus”—in other words, the country’s full utilization of its burgeoning working-age population. In 2000, before joining the World Trade Organization, China had a population bump in the 25 to 35 age band (see Figure 2). This was the result of a population explosion in the 1960s, which had in turn been a reaction to the failure of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, a failed policy to boost agricultural and industrial output that resulted in over 30 million people tragically starving to death at the beginning of that decade. However, China fully utilized the additional workforce by joining the WTO and becoming the factory for the world.

The children of these baby-boomers were born in the 1980s. This generation, over 40% of whom went to university, is now in its prime and can be said to be contributing to China’s current transition to a high-tech economy (the phrase “engineer bonus” has been coined).

However, this “population bonus” was subsequently countered by a decline in population that has been termed a “population onus.” When we look at China’s future, assuming the internationally accepted definition of the working age population as persons aged 15–64, we can estimate that the workforce will decrease by around 1% every year from now through 2040.

To cancel out the suppressive effect on economic growth of this population decline, China will need to improve its economic productivity by an average of 1% per year. While the rapid automation of production and digitization of the economy being seen in China at the moment, in particular with the embrace of artificial intelligence and big data, will likely cancel out the negative effects, this does not alter the nation’s fate of having 1% deducted from the fruits of improved workforce productivity every year.

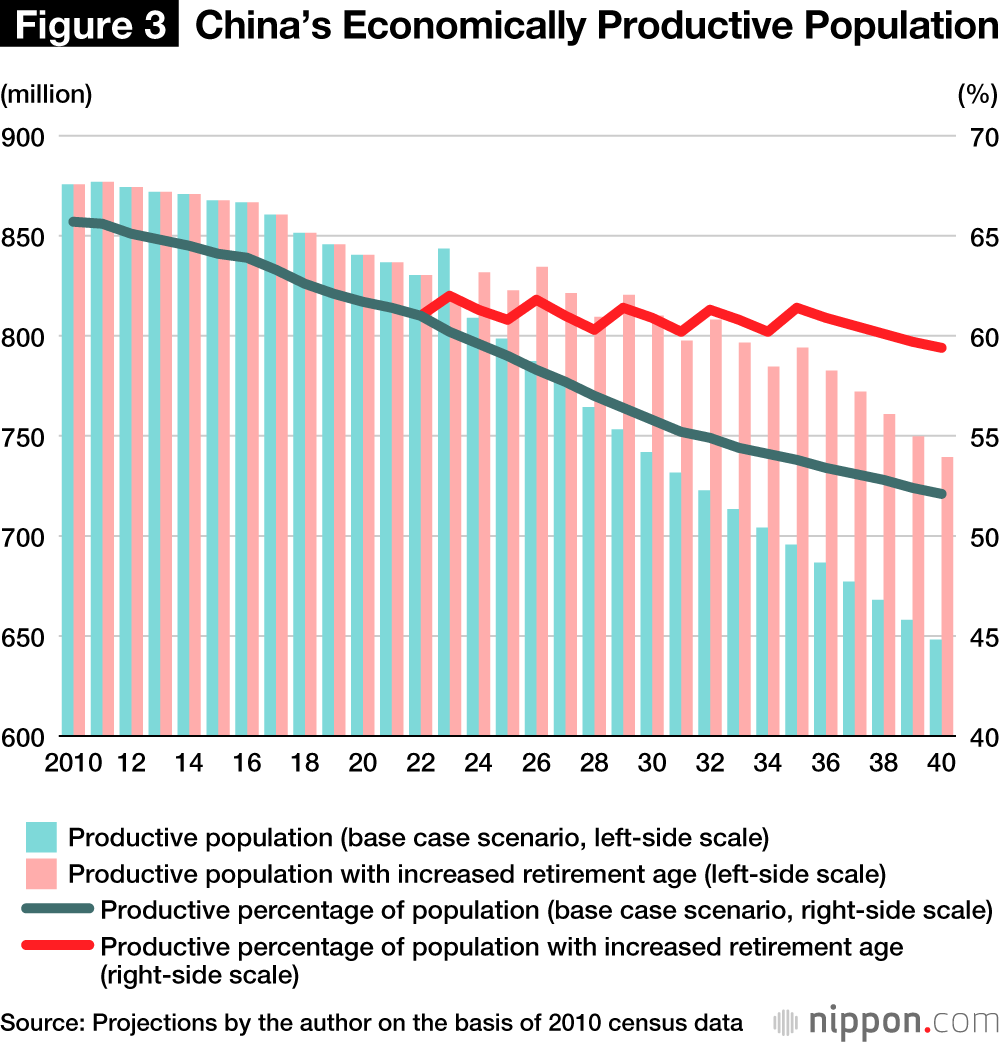

However, it was when considering this problem that I noticed that China has one other trick available to it. In 2012, I formulated a model for predicting future changes in Chinese demographics by combining 2010 census statistics with annualized data on the numbers of births and deaths. Revisiting this model, I note that while its projections need to be corrected using the latest birth data, China’s population makeup will not change significantly in the future, making it reasonably capable of projecting future populations. The projections used in Figure 3 and 4 are based on this model.

It is still customary for Chinese men to retire at 60 and Chinese women to retire at 55, with the working population defined as men aged 16 to 59 and women aged 16 to 54. However, in view of the future burden of pension payments, the government is planning to raise the retirement age to 65 for men and 60 for women. Assuming that over the space of the next 15 years both men and women can be encouraged to work five years longer, as shown in Figure 3, the economically productive population is projected to remain around 60% of the total. If this scenario comes to pass, the negative effects of the declining fertility rate and aging population on supply will therefore be more or less avoided over the coming 20 years.

However, the policy to raise the retirement age is coming under fire from middle-aged Chinese, who complain that just when they thought they would be able to collect their pensions and spend their retirements pursuing their hobbies and taking care of their grandchildren, the government is telling them to keep working.

Larger Impact Manifests Itself in Society and Social Trends

My view that China may be able to avoid the “population onus” effect of its declining fertility rate and aging population may be counterintuitive. Rather than the Chinese economy, though, I believe it is China’s national spirit and social trends that will suffer the most.

The greater the proportion of young people in a society, the more dynamic it is. At the same time, younger societies are prone to unrest. The radicalization of the student movement in many Western countries in the years around 1970, a quarter of a century after World War II, and the recent political instability in the Middle East are both attributed to burgeoning populations of young people.

As discussed above, China experienced two population bumps in the latter half of the twentieth century. A job shortage at the time those cohorts reached working age would have brought about social instability, so in this respect we can say that the Chinese Communist Party did its job well.

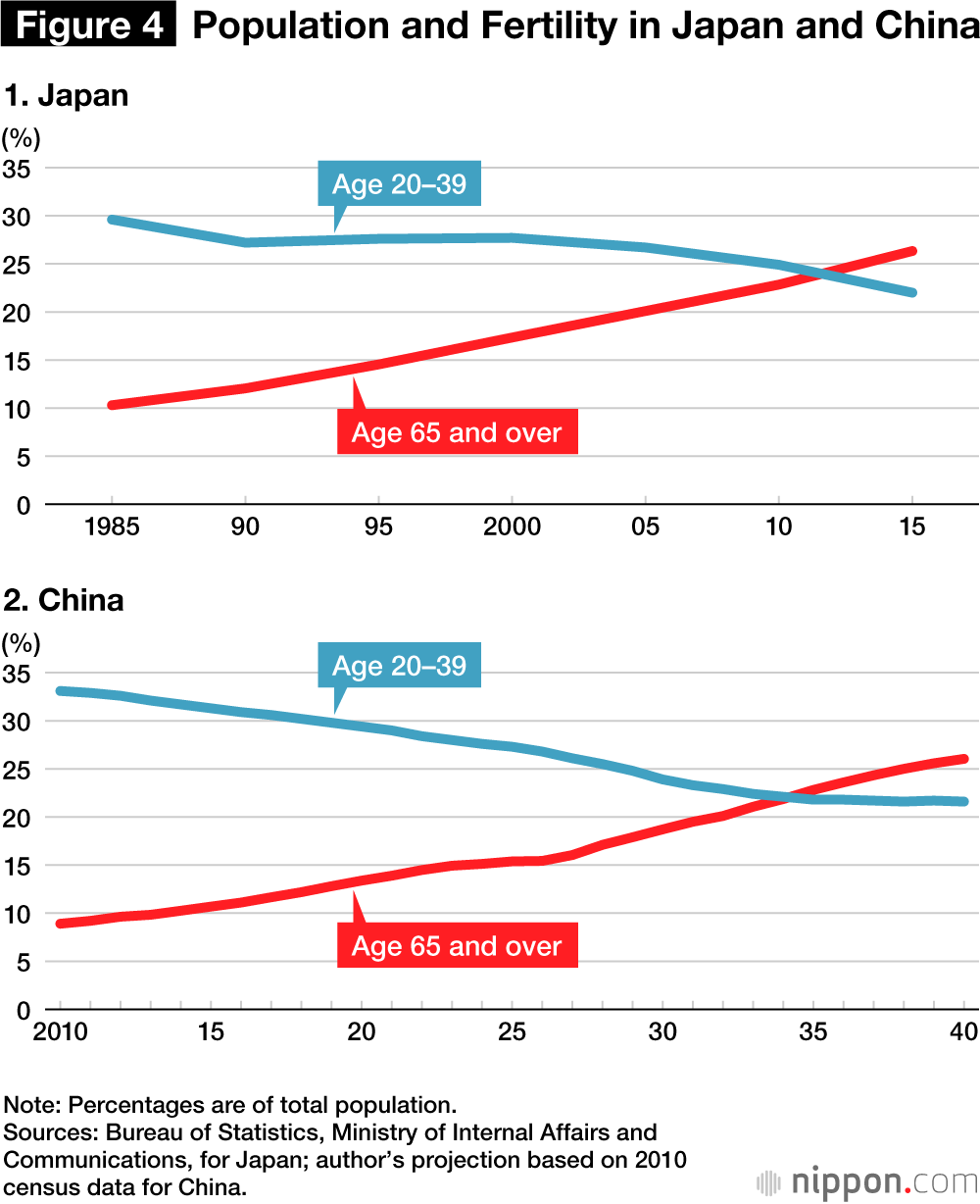

As the percentage of young people in a population declines, however, the opposite is true: society loses its vitality and there is an increasing tendency to seek safety and security. Japan right now is a classic example of this.

It is said that in Japan, the 65 and over age group eclipsed the 20‒39 age group around 2012. Projections of China’s future demographic makeup using population modelling show that China will undergo a similar inversion around 2034, as seen in Figure 4. In fact, because China’s fertility rate is dropping as well, this might happen even sooner.

Every issue has a positive and negative side. While China has used population increases, in particular the increase of its young population, to its advantage in the past, in the future, as the decline in the country’s fertility rate and the aging of its population become more pronounced, negative effects will become manifest.

Even if China is able to avoid the negative economic effects of a declining workforce, there is ample chance that national spirit and social trends will stagnate as the public becomes more risk-averse. The reappointment of Xi Jinping also makes it likely that the Party leadership will continue to age. One must ask whether China will be able to overcome this risk.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A mother looks for a marriage partner for her son at a matchmaking event in a Beijing park; China’s one-child policy has created a skewed gender ratio, making it difficult for men from poorer families to find wives. © AFP/Jiji.)