Photographer Irwin Wong Captures the “Obsessed” Subcultures of Japan

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s Obsessions Go Global

In the age of streaming and online shopping, it’s easy to forget how Japan’s cultural exports were once far from accessible to much of the world. In the early 1990s, finding some anime to watch might require a trip to the video shop, while sourcing sushi ingredients could take a journey to the Asian supermarket.

But today, with almost anything from anywhere instantly downloadable or orderable, things considered alien and exotic have become ordinary. Mirin and miso are on the shelves of ordinary supermarkets. Words like kawaii and otaku have entered the pop-culture lexicon. Even the venerable London Times recently described an English politician as performing “Margaret Thatcher cosplay.”

In Japan, though, the kaleidoscope of subcultures is as dizzying and strange as ever. That is vividly recorded in Irwin Wong’s new photobook, The Obsessed: Otaku, Tribes, and Subcultures of Japan.

To take just three of the 42 subculture topics and individuals covered in the book, there are the tanganmen, people who wear one-eyed masks, the 1/1 Scale Model Club, who spent seven years making a full-size replica of a German armored vehicle, and Kobayashi Hideaki, also known as Sailor Uniform Grandpa.

Tanganmen, people who wear one-eyed masks, pose at a convenience store. (© Irwin Wong, Gestalten)

Wong, who took the majority of the book’s photos and wrote much of the text, brings together the fruit of several years’ research and photoshoots around Japan. As he writes in the book’s foreword, what links his subjects is that they “pursue their hobby to a point beyond all common sense and reason.”

Kobayashi Hideaki, the “Sailor Uniform Grandpa.” (© Irwin Wong, Gestalten)

Hard Thinking About Otaku

In Japan, such people are often called otaku, which was in fact the publisher’s original suggestion for the book’s title. But Wong was reluctant to use the word.

The word has different nuances in English and Japanese. Outside of Japan, otaku often refers to someone who loves Japanese anime, manga, Japanese snacks, or other pop culture exports. In Japan, however, the meaning of otaku is more complex.

On the one hand, it can suggest an almost dangerous, antisocial obsession. “I knew a lot of the people I included would not react kindly to being in a book called otaku,” Wong says. Yet, it can also have a positive meaning of someone who is obsessed or highly knowledgeable about a thing. So, there are high-end audio otaku and coffee otaku, as well as cosplay otaku and plastic model otaku.

The artist Toriena is a leading figure in the chiptune music scene, which uses the sound chips in vintage video-game consoles to create works of surprising complexity and depth. (© Irwin Wong, Gestalten)

Wong wanted to focus on the latter in his book project. To prepare, he drew up a list of potential topics.

“I wanted to show the diversity of subcultures on offer in Japan, and to show how different and interesting they are,” he says. And he wanted to convey “the depths of dedication” each person goes to in the pursuit of that subculture lifestyle.

Social media and the internet were the easiest way to find and contact such subculture enthusiasts. And when he did get in touch, often he found that they were more than happy to be featured.

“A lot of the subcultures actually do it to be seen,” says Wong. “They are very open to people coming in and taking a look.”

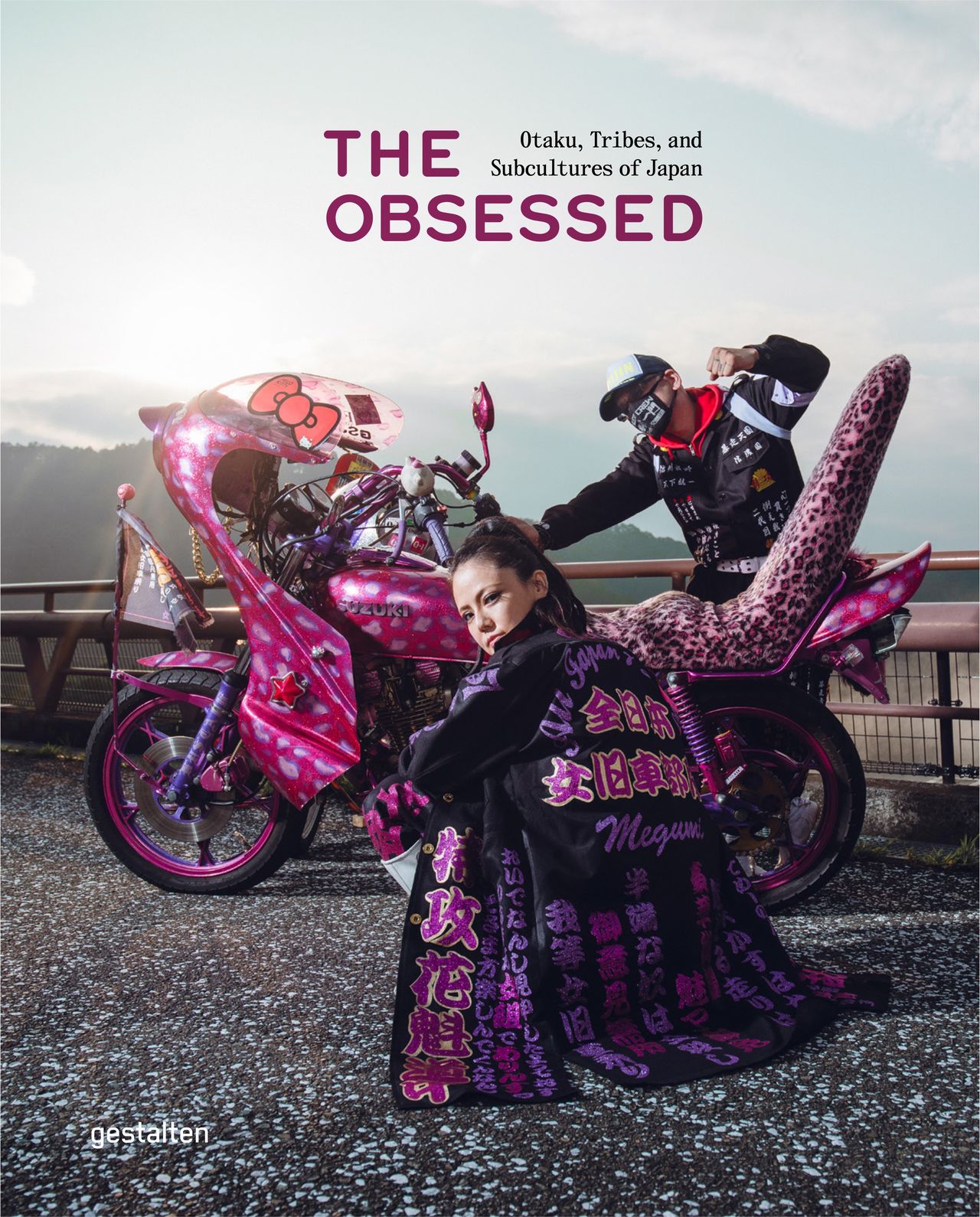

At first, Wong imagined that former members of bōsōzoku biker gangs, a tribe associated with juvenile delinquency and crime, might be somewhat publicity shy. But that wasn’t so with the pair who appear on the book’s cover.

“I literally just went up to them and said, ‘Hey, I’m doing a book. You guys look really interesting. Can I photograph you? And they were like, sure, yeah.’”

On the other hand, Wong says that some subjects were “very concerned about how the images will be used and how they themselves will be portrayed.” He worked to reassure them that his book would be about the human motivation behind subculture obsessions, not their “weirdness.”

Incidentally, the legendary rockabilly dancers of Harajuku, who also feature in the book, were wary for a different reason. They were worried “about being put in a book with a whole bunch of other people they might not think are cool,” Wong laughs.

Artisans and Other Obsessives

Geeks, enthusiasts, and aficionados exist in every culture. What is it about some Japanese people that drives them to pursue their obsessions so far?

Wong notes that many people he photographed and interviewed were “on the fringes of Japanese society.” Their obsessions, he says, were “something that kind of saved them and gave them a purpose and meaning.”

And even on the fringes of Japanese society, subculture enthusiasts find new community.

“You’ve got to be part of a group here,” says Wong. “Even when these people find their subcultures, they still find a group, a place to belong among other like-minded people. That’s part of the reason why it proliferates and becomes so crazy. They compete with each other . . . it just becomes more outlandish as time goes on.”

There’s another way to describe this: kodawari, or attention to detail. That suggests an interesting connection with Wong’s previous book on Japanese artisans, his 2019 Handmade in Japan.

He points out that obsessive enthusiasts and artisans share “amazing attention to detail and constant honing of skill.” In fact, Wong believes that many of the people in his book could be called artisans in their own right. Take the group of mechanics from Nagoya who repair and restore old American cars.

“There’s no other word for them than artisans,” Wong argues. “They don’t just repair these cars, they elevate them.”

Harajuku Bridge and Instagram

The Obsessed contains four essays to accompany Wong’s photos and interviews: by Patrick W. Galbraith on otaku, Joshua Paul Dale on kawaii, Dino Dalle Carbonare on car culture, and Philomena Keet on Harajuku fashion.

Interestingly, Keet writes how even before the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, Harajuku’s street fashion scene had been diluted by international fast fashion. She laments how some of Tokyo’s color and vibrancy has been lost. For example, the boys and girls who used to hang out on Jingūbashi, also called Harajuku Bridge, have gone.

Yet, Japan’s subculture enthusiasts—many of whom live well away from Japan’s urban centers—probably aren’t too worried. The internet has changed everything for those who create Japan’s subcultures, as well as those who consume them.

As Wong puts it: “You don’t need to hang out on the bridge and have people shove cameras in your face now. You can have your photo on Instagram, where people follow you. It’s probably a lot easier for them, to be honest.”

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Banner photo: Bōsōzoku bikers from the cover of Wong’s The Obsessed. All photos © Irwin Wong/Gestalten.)

The Obsessed: Otaku, Tribes, and Subcultures of Japan

By Irwin Wong

Published by Gestalten, 2022

ISBN: 978-3-96704-008-1