Tokyo’s Little Mount Fujis

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

It is said that faith can move mountains. In Japan it has even been known to create them—small ones at least—thanks to Fujikō, religious associations devoted to the worship of Mount Fuji that flourished in the Edo period (1603–1868).

These groups built local, miniature replicas called fujizuka for members to climb. Many of these mounds still dot the Tokyo metropolitan landscape, making it possible to scale Japan’s “highest peak” and still be back in time for lunch.

The Cult of Fuji

A stone marker indicates the eighth station on the Shitaya-Sakamoto fujizuka.

A stone marker indicates the eighth station on the Shitaya-Sakamoto fujizuka.

Japanese from time immemorial have venerated Mount Fuji for its height, beauty, and sanctity. A long list of historical figures have summited the peak, including priest Kūkai, founder of Shingon Buddhism and the henro pilgrimage, and legendary regent Prince Shōtoku, who, according to legend, conducted his climb astride a black steed. For much of history, however, most residents of Japan were content to admire the conical peak from afar and leave the demanding task of scaling the sacred mountain to adherents of Shugendō, or mountain asceticism.

This relationship with Fuji began to change as the teachings of Hasegawa Kakugyō (1541–1646), a semi-legendary figure known as the father of the Fujikō movement, took root among inhabitants of the feudal capital of Edo, now Tokyo.

Fujikō considered ascending Mount Fuji an important religious rite. They solicited funds from the community to sponsor annual pilgrimages, but as the number of congregations grew—by some accounts there were more than 800 at the movement’s height—it became impractical for all adherents to join these holy excursions. To accommodate members unable to leave the capital, local associations in the mid–Edo period began constructing miniature Mount Fujis.

The associations were extremely influential in forming how Fuji is seen today, introducing features familiar to modern climbers, such as the 10 stations along routes and the ohachimeguri trail around the caldera.

Neighborhood Mountains

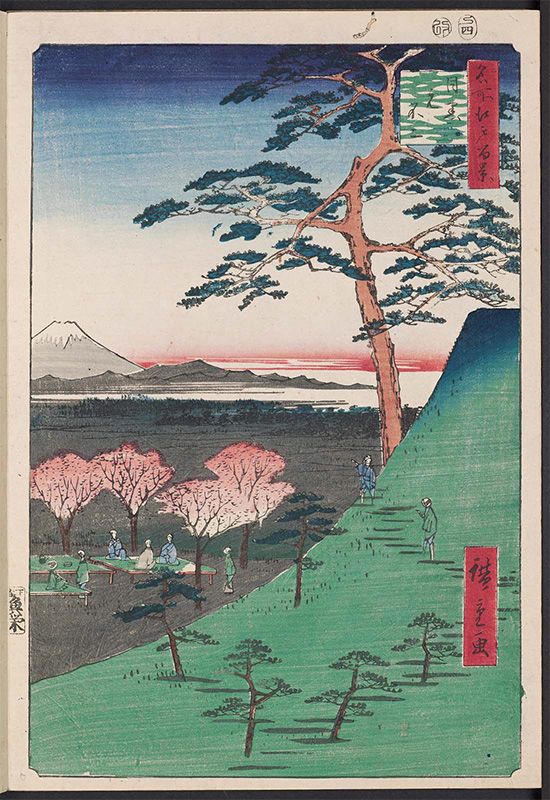

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Meguro moto-Fuji, from One Hundred Views of Edo. (© National Diet Library)

Utagawa Hiroshige’s Meguro moto-Fuji, from One Hundred Views of Edo. (© National Diet Library)

A sect headed by Takada Tōshirō is credited with building the first fujizuka in 1780 using volcanic rocks and soil painstakingly hauled from the mountain. The replica, which is said to have taken over nine years to complete, jutted 10 meters into the sky and recreated station markers, shrines, stone monuments, and other features of the real Fuji. Affectionately known as the Takada Fuji, it was reputed to be a popular site continually abuzz with activity. It still stands today, quietly hidden within the confines of the Mizuinari Shrine near Waseda University, where it was moved in 1963 when the university expanded its campus.

Other early examples of mini Fujis were the 12-meter Meguro Moto-Fuji built in 1812 and Meguro Shin-Fuji constructed near its sister mountain in 1819. Renowned for their beauty—the artist Utagawa Hiroshige immortalized both in his famous woodblock print series One Hundred Views of Edo—these fujizuka were eventually cleared away as modern Tokyo grew.

The most esteemed fujizuka were the so-called seven Edo Fujis. This numerical designation appears to be somewhat arbitrary, and records indicate that there were many more respected mounds in neighborhoods around the city. Many of these have survived into the modern day, including the mini Fujis of Ekoda, Jūjō, Otowa, Takamatsu, Sendagaya, Shitaya-Sakamoto, and Shinagawa. There are also numerous replicas outside Tokyo, such as the Kizoro Fuji in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture. Built in 1800, it ranks as one of the oldest fujizuka in Japan.

Flooding, conflagration, and wartime bombing have claimed a number of mounds, but there are still over 60 of varying ages in and around Tokyo, most of which can still be climbed today. New mounds are also being added to the list, although these tend to have less to do with Fujikō than with attracting tourists. One such peak is a 1.5-meter Fuji that debuted in the Tokyo neighborhood of Asakusa in June 2016.

A miniature of the Sengen Shrine Oku no Miya on the summit of Mount Fuji sits atop a fujizuka in Setagaya, Tokyo.

A miniature of the Sengen Shrine Oku no Miya on the summit of Mount Fuji sits atop a fujizuka in Setagaya, Tokyo.

Recreating Fuji

Fujizuka are most commonly affiliated with the Fujisan Hongū Sengen Jinja, the main shrine of Mount Fuji, and are festooned with replica monuments, statues, and other objects of worship. There are even some that re-create well-known natural features, such as the mountain’s caldera and the Otainai lava caves, where pregnant followers prayed for safe childbirth.

Fujikō typically built mounds from the ground up, piling rocks and soil before adding a finishing cover of rust-colored volcanic stones from Mount Fuji. Some replicas took advantage of existing topography, such as the Komagome and Jūjō Fujis that were erected atop prehistoric burial mounds. These two fujizuka are thought to have originally been built as shrines in 1629 and 1766, respectively, but were later transformed into mini Fujis.

While Fujikō are no longer active today, many fujizuka retain their iconic status and are the center of various neighborhood festivals during the year. The most important of these events is the observance of yamabiraki, the official start of the climbing season on the real Mount Fuji, in late June and early July. At this time several older mounds, particularly those protected as important cultural properties, temporarily lift their moratoriums on climbing to allow revelers to ascend their ancient peaks.

A statue of Jikigyō Miroku, an early leader of one of two lineages of Fujikō.

A statue of Jikigyō Miroku, an early leader of one of two lineages of Fujikō.

Mount Fuji’s listing as a World Heritage site in 2013 has helped renew interest in the mounds, and many communities have taken steps to preserve local Fujis that have fallen into disrepair. In 2015 Fuji City began conducted an archeological dig at the Suzukawa Fuji, Shizuoka Prefecture’s only remaining fujizuka. And early in 2016, local volunteers in Shiki, Saitama Prefecture, rebuilt steps and other parts of the local Tagoyama Fuji, opening it to climbers for the first time in 30 years.

Climbing fujizuka may not provide the same thrill as ascending the real Mount Fuji, but the replicas do have a distinct charm. Considering the crowds on Fuji during climbing season, some may prefer to summit one of Tokyo’s mini mountains and then grab a coffee or a bite to eat.

The gates of the Shitaya-Sakamoto fujizuka are opened for several days each year to celebrate the start of the official climbing season on Mount Fuji.

The gates of the Shitaya-Sakamoto fujizuka are opened for several days each year to celebrate the start of the official climbing season on Mount Fuji.

(Banner photo: Climbers scale Shitaya-Sakamoto Fuji during yamabiraki, or the opening of the Mount Fuji climbing season. All photos © Nippon.com unless otherwise noted.)