Japan’s “Doctor Locust”: Scientist Building Resilience Against an Ancient Menace in the African Desert

Science Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Taking On an Old Menace

Japanese entomologist Koutaro Ould Maeno does fieldwork in one of the harshest environments on the planet, the Sahara Desert. A senior researcher at the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences, he is going head-to-head with the desert locust, a scourge as old as history. These flying insects are the bane of farmers in the region, decimating vital crops and threatening communities with famine. While insecticides help keep ravenous swarms in check, Maeno is working to unlock the mysteries of the bug’s biology in a bid to control outbreaks and minimize the use of costly and harmful chemicals.

Recognizing Maeno’s determination, Mohamed Abdallahi Ould Babah Ebbe, the former director of the Mauritania’s National Anti-Locust Center, bestowed upon him the honorary name Ould, meaning “son of” in Arabic. In Japan, though, he is best known by the moniker “Doctor Locust.”

A swarm of locusts in the Sahara Desert. (© Koutaro Ould Maeno)

Koutaro Ould Maeno dressed in traditional Mauritanian garb. © Kawabata Hiroto.

Maeno, who has chronicled his fieldwork in two award-winning books, first studied the desert locust in the laboratory. However, he found the environmentally controlled conditions artificial, prompting him to trade his air-conditioned lab for the heat and harshness of the open desert of Mauritania, where he could scrutinize his subject in its natural environment.

In 2011, Maeno packed his bags and headed to the vast, arid expanses of Mauritania, the frontline of desert locust outbreaks and home to the recently established National Anti-Locust Center. With the center’s support, he conducted field investigations and interviews on-site, seeking to better understand locust ecology. In the process, he realized that almost no fieldwork had been carried out for nearly 40 years.

Desert locusts primarily inhabit remote areas, and their populations fluctuate greatly depending on weather conditions and other factors, making the insects extremely difficult to locate in the field. When swarms do form, they can travel huge distances, requiring anyone hoping to study them to remain on the move. Then there is the matter of safety, as locusts are found in isolated regions with harsh environments that are often plagued by political instability. Taken together, conducting long-term research on desert locusts in the field is a highly challenging endeavor.

A tent provides shelter and serves as the base of operations for Maeno’s field research. (© Koutaro Ould Maeno)

Locusts perch on Maeno as he conducts fieldwork. (© Kawabata Hiroto)

Subsequently, there had been little attempt among authorities and farmers to study the ecology of wild locusts in order to build a comprehensive strategy to control and prevent outbreaks. Rather, the primary approach was simply to deal with swarms as they arose by spraying them with insecticides, an expensive and environmentally risky tactic. Seeing an opportunity to contribute, Maeno and his local collaborators set about conducting fieldwork with the hope that, by focusing their attention on the biology and behavior of the species, their research might lead to the development of an effective control strategy.

Before heading into the field, Maeno procured most of his own materials—insect cages, food for locusts, equipment for conducting experiments—at local markets. He typically needed to cleverly adapt what was available to suit his needs. “It was a challenge,” he says. “But growing up, I’d been taught to be resilient, to adjust and improve my approach according to the situation at hand.”

An insect cage Maeno created using available materials in Africa. (© Koutaro Ould Maeno)

Working in the Sahara presented other issues as well. “There’s no Internet in the desert,” he quips. “I can’t simply ask AI, as is the norm today, when I’m stuck. The limitations have really taught me to use my head.”

Time is also a commodity. “I’m out in the field for ten days at the longest, so it’s a race to gather the best data I can,” he says. This means weighing which experiments to do given existing conditions. “I have to tailor my research according to the demands of the surrounding environment and my own physical state.”

Creating a Support Network

Maeno says that the desert locust remains a relatively little-understood species, but researchers around the globe are working together to unlock its biological secrets. “Scientists across various fields are sharing their findings to provide humanity with a clearer picture of these insects,” he explains.

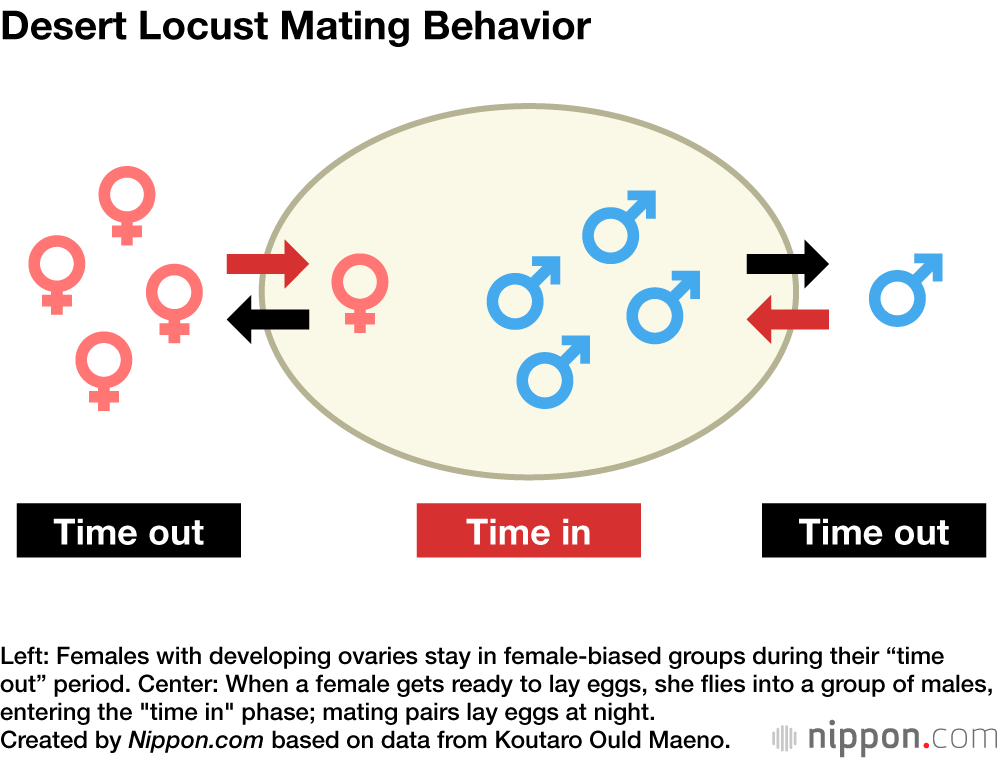

Early in his fieldwork, he made a surprising discovery when collecting locusts from a group. All the insects he caught were male, leading him to hypothesize that the species lives in sex-biased groups as part of its mating habits. He discussed this phenomenon with his colleagues at the Mauritanian National Anti-Locust Center and Illinois State University professor Douglas Whitman.

Maeno (second row, right) with Douglas Whitman (in the rear at center) and his students. (Courtesy: Koutaro Ould Maeno)

“Field work is my strong point,” Maeno declares, “but at the time, I was still young and acutely aware of my own inexperience.” He understood that even if he had a good idea, without being able to test it experimentally, it would not advance locust research. Whitman provided invaluable advice and taught Maeno effective experimental techniques and methods, which he utilized in proving his hypothesis.

Maeno’s work in Africa led in 2014 to a post at Kyoto University’s Hakubi Center, where he joined the laboratory of renowned entomologist and termite expert Matsuura Kenji. Maeno says he grew as a scientist under Matsuura, whose open style encouraged everyone in the lab, from students to post-doctorates, to share their views and opinions. “Professor Matsuura was generous with his knowledge and experience, readily sharing what he’d learned over his many years as a researcher, such as fieldwork tips, research approaches, and even advice on how to write scientific papers. Building on my experience in Africa, my two years in Matsuura’s laboratory were a tremendous period of growth.”

An Inspirational Tale

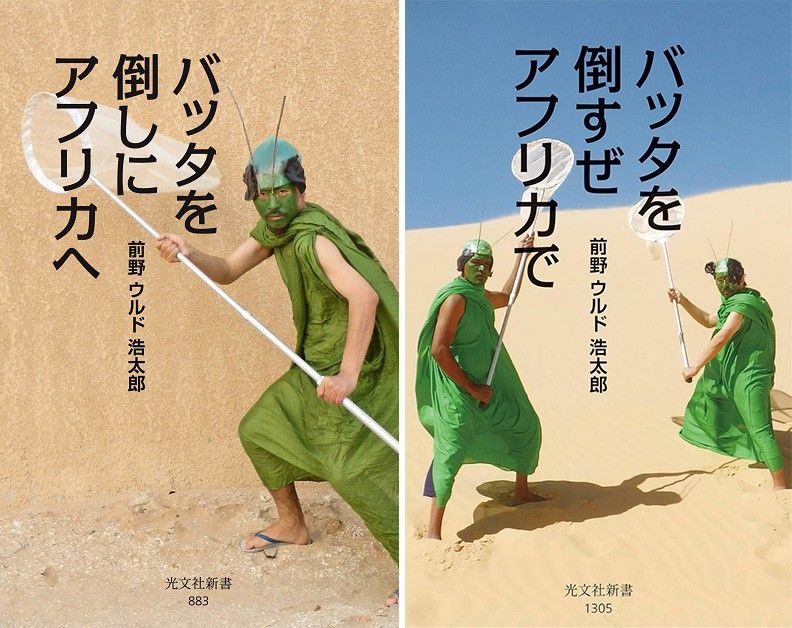

Desert locusts are a niche field for a Japanese researcher to find himself in, and Maeno took to posting stories about his tribulations in Africa on social media to boost awareness of his work and the region’s locust problems. This led to his first book for the general public detailing his work in Africa, titled Batta o taoshi ni Afurika e (A Bug-Catcher’s Adventures in Africa). “I wanted to contribute to bettering society,” he declares. “Most people don’t have the time or know-how to decipher English-language research papers, so I thought if I wrote a book in Japanese detailing my struggles and triumphs in the desert, it might increase public awareness and inspire others to take on new challenges.”

The work was a hit, and encouraged by the positive response—he had initially assumed critics would deride him for taking time away from writing research papers—he published a sequel in 2024, Batta o taosu ze, Afurika de (Taking On the Locust in Africa).

Maeno’s two books are entertaining windows into his research on desert locusts. The prize-winning works have together sold over 360,000 copies. (© Kōbunsha Shinsho)

Today, Maeno busily travels the globe conducting fieldwork and taking part in international research projects. His books have earned him a modicum of fame in Japan, where he often sits for interviews and gives presentations to junior high and high school students.

“With the way Japanese society and economy are today, the thought of chasing one’s dream can seem extremely daunting,” he says. “By sharing my journey as a field researcher, I want to ease the concerns of young people and take a step toward building a world where individuals feel emboldened to wholeheartedly pursue their interests. Hearing about someone else’s difficulties helps us realize that we’re not alone in our struggles. Nothing would make me happier than if my story of flying to Africa to study desert locusts inspires even one person to aim for the stars.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Playfully dressed as vegetation, Koutaro Ould Maeno attempts to attract a swarm of locusts. Courtesy: Koutaro Ould Maeno.)