Sugihara Chiune: “Japan’s Schindler”

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Forthcoming Film

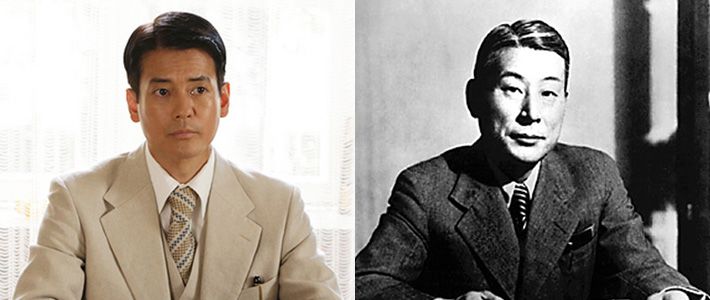

December 2015 will see the release of a film telling the story of diplomat Sugihara Chiune, who helped save the lives of more than 6,000 Jewish refugees while working in Lithuania during World War II. Karasawa Toshiaki plays the lead character in Sugihara Chiune (Persona Non Grata), which is directed by Cellin Gluck, an American born and brought up in Japan.

In January 1985, Sugihara, who is sometimes referred to as “Japan’s Schindler,” was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by the Israeli government and honored in a section of the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial. He is the only Japanese person to have received such an honor.

By contrast, official Japanese acknowledgment of Sugihara’s efforts was longer in coming. Sugihara was forced out of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1947 after ignoring orders and continuing to issue visas until Japan’s consulate in Lithuania closed in 1940. It was not until 1991 that MOFA sought to make amends.

At the time Suzuki Muneo, then parliamentary vice-minister for foreign affairs, invited Sugihara Chiune’s widow Yukiko to a ceremony in which MOFA apologized to the family and restored the reputation of the former diplomat, who was praised for his humanitarian and courageous actions. Nippon.com spoke to Suzuki, who is now head of the Hokkaidō-based New Party Daichi.

Defying Orders and Issuing Visas

INTERVIEWER How did you become involved in moves to rehabilitate Sugihara?

SUZUKI MUNEO In 1991 I was parliamentary vice-minister for foreign affairs. That was the year of the Gulf War and attempted coup against Mikhail Gorbachev. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, I was sent in October of the same year as a special envoy of the Japanese government to establish diplomatic relations with the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which had regained their independence.

When I heard the name Lithuania, I immediately thought of Sugihara Chiune and how he issued exit visas to Jews despite Matsuoka Yōsuke, the foreign minister of the time, forbidding it. The world now recognizes his achievement.

INTERVIEWER Was Sugihara forced to resign after the war because he’d disobeyed MOFA orders?

SUZUKI Sugihara himself believed that he lost his position because he hadn’t followed instructions and I heard that all connections to MOFA were immediately broken off. As I was going to Lithuania, I was determined to restore his reputation.

MOFA Resistance

SUZUKI But the problem was in persuading MOFA. When I suggested my idea to Satō Yoshiyasu, who was then deputy vice-minister for foreign affairs, he told me there was no need. He said that Sugihara had resigned as part of downsizing after Japan was defeated in the war, when a third of employees were let go. Satō felt that as Sugihara had not lost his job to take blame for ignoring orders, it was best to just quietly leave things as they were.

Under normal circumstances I would have taken it no further, but I persisted, saying he left the foreign office after being asked to resign by the administrative vice-minister because of the visas he’d issued. Although Sugihara has passed away, family members have told me that he felt he’d been forced out. Despite the world’s praise of Sugihara, I was indignant about the ministry not properly recognizing a worthy predecessor. I continued to press. But the reply remained that Sugihara’s resignation had not been a punishment from MOFA.

INTERVIEWER Sugihara left the ministry in June 1947.

SUZUKI That’s correct. He retired at his own request after returning to Japan. But he clearly recalled being asked to do so by the administrative vice-minister of the time. For that reason, I firmly insisted that it was essential to clear Sugihara’s name. Ultimately, I was able to get my idea through. On the third day, Satō said, “I’ll leave you to organize it.”

Great Humanity

INTERVIEWER Were you inspired to act by Sugihara Yukiko’s book Rokusennin no inochi no biza (Visas for Life)?

SUZUKI I was deeply moved when I read her work. In 1940, Germany and the Soviet Union were not yet at war. The historical background was that the two countries signed a nonaggression pact in August 1939 and Germany invaded Poland in September, triggering the start of World War II.

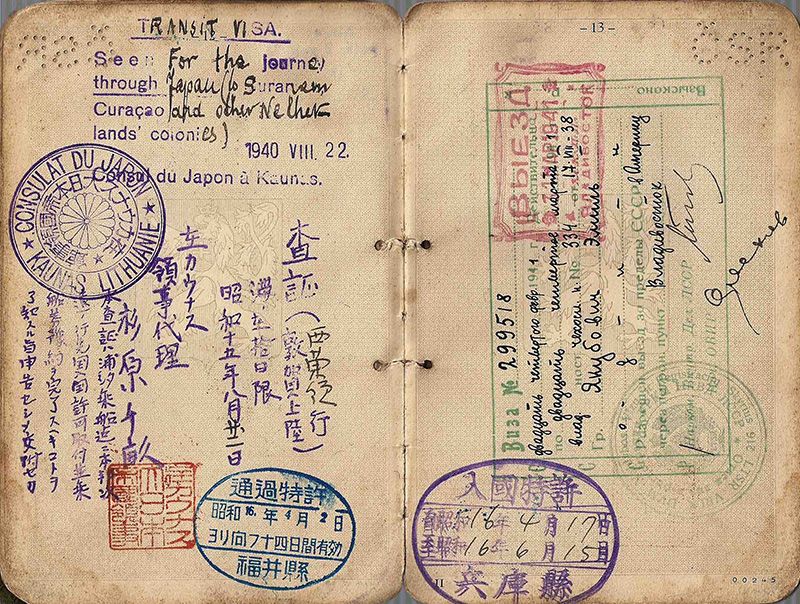

In 1939 Sugihara was made vice-consul of the Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania and in August 1940, the three Baltic states were annexed by the Soviet Union. An election had been held in Lithuania in July, which left Jewish refugees in the country fearing for their safety and they continued to throng into the Japanese consulate pleading for visas from immediately after the election until the end of August. Even when the consulate was closed, Sugihara kept on issuing visas from the hotel where he was staying.

Visa handwritten by Sugihara Chiune

Visa handwritten by Sugihara Chiune

Knowing all this, I explained in detail to Satō the great sense of humanity with which Sugihara had performed his duties.

INTERVIEWER And the ceremony took place on October 3, 1991.

SUZUKI Sugihara Chiune’s wife Yukiko and their oldest son were invited to the Iikura Guest House and I apologized for the disrespectful way they had been treated.

A Human Being Before a Diplomat

INTERVIEWER After that, Sugihara’s reputation continued to grow.

SUZUKI In April 1999, Prime Minister Obuchi Keizō went to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange during a visit to the United States. CME Chairman Emeritus Leo Melamed was one of the world’s most successful Jewish people and should have been near Prime Minister Obuchi. But he came up and was talking, although I was only deputy chief cabinet secretary. The reason, I found out later, was that he had survived the war by receiving one of the visas issued by Sugihara.

INTERVIEWER After leaving MOFA, Sugihara later spent 15 years in the Soviet Union from 1960, working for a trade company. But he didn’t say anything about what he had done during the war.

SUZUKI Sugihara was a human being before he was a diplomat. There were many innocent women and children among the Jews who gathered at the Kaunas consulate. He sent a telegram saying they should be given visas, but there was no reply from the ministry in Japan. Foreign Minister Matsuoka Yōsuke thought no visas should be issued because of the pact with Germany and Italy, at a time when German forces were sweeping across Europe. Sugihara asked for permission three times, but each time he was refused.

Then he decided to do the obvious thing as a human being. He certainly thought to himself, “If I don’t write visas for these people, they will certainly suffer and lose their lives. These women and children with absolutely no connection to the war.”

So he started writing visas, but it took every effort to write 200 each day. In the end he saved 6,000 people’s lives.

A Street Named Sugihara

INTERVIEWER You went to the site of the former Japanese consulate in Kaunas when you visited Lithuania.

The former Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, where Sugihara worked as vice-consul from 1939 to 1940.

The former Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, where Sugihara worked as vice-consul from 1939 to 1940.

Lithuanian stamp featuring a portrait of Sugihara Chiune

Lithuanian stamp featuring a portrait of Sugihara Chiune

SUZUKI While negotiating the restoration of diplomatic relations with the Lithuanian leader Vytautas Landsbergis, I said that it would be good if the country could do something to commemorate Sugihara. He immediately replied, saying the street where the Japanese consulate in Kaunas used to be would be renamed “Sugihara Street.” It is still Sugihara Street today.

Landsbergis offered to show us to the former consulate, preparing a police escort with patrol cars and motorcycles. The building had become an apartment block. As we arrived with sirens blaring and displaying Japanese flags, the residents thought that “Japan has come to requisition the building” and nobody came out. When we explained that this wasn’t the case, they streamed outside. And as we explained the history, it was wonderful how everyone responded positively.

Commemorative Plate

INTERVIEWER What happened after that?

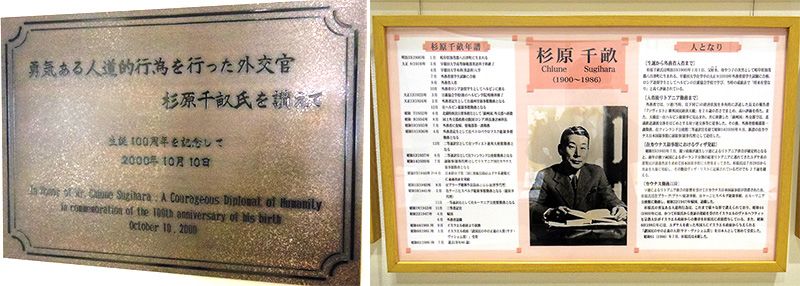

SUZUKI After the apology and the restoration of Sugihara’s reputation, Watanabe Michio became foreign minister in the cabinet of Prime Minister Miyazawa Kiichi. But unfortunately, under pressure from bureaucrats, he just said that Sugihara had been let go as an administrative act. Then Kōno Yōhei became foreign minister and I thought it was essential to make some concrete move, so I had an official plate put up in the MOFA diplomatic archives building to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of Sugihara’s birth. For some reason, the ministry treats its non-career workers coldly. But I think MOFA should be proud of its former diplomat and let the world know about what he did.

An unveiling ceremony for the Sugihara Chiune commemorative plate (left) in the lobby of the MOFA diplomatic archives building was held on October 10, 2000.

An unveiling ceremony for the Sugihara Chiune commemorative plate (left) in the lobby of the MOFA diplomatic archives building was held on October 10, 2000.

Tsutsumi Seiji [businessman and author], who recently passed away, wrote an opera based on Sugihara. I took up the invitation to attend it when it was showing in Yokohama. And I’m looking forward to the Tōei film this winter.

(Originally written in Japanese and published on May 19, 2015. Translated from an interview by Harano Jōji, representative director of the Nippon Communications Foundation, on April 7, 2015. Banner photo: Karasawa Toshiaki (left) portraying Sugihara Chiune © 2015 Sugihara Chiune Production Committee. Sugihara Chiune (right). © NPO Chiune Sugihara Visas for Life.)