Learning Japanese with Manga Author Umino Nagiko

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

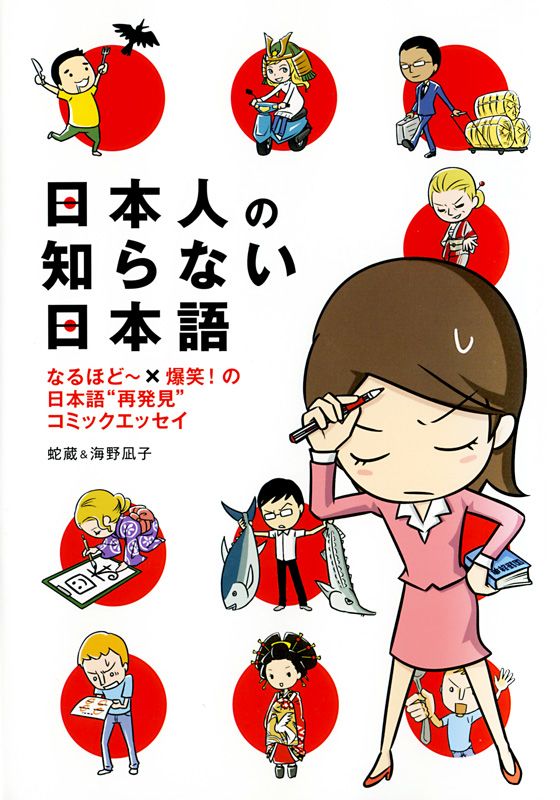

Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo (The Japanese the Japanese Don’t Know)

Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo (The Japanese the Japanese Don’t Know)

When the Japanese language teacher Umino Nagiko turned her classroom experiences into a manga, created with her friend Hebizō, it became an instant bestseller. As the title Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo (The Japanese the Japanese Don’t Know) indicates, on one level it was a chance for Japanese people to rediscover their own language. The manga also appeals through comical misunderstandings and cross-cultural communication with a cast of enthusiastic international students.

There are now four main entries and a supplementary workbook in the series—which has sold more than 2 million copies—as well as a television adaptation. They cover such areas as keigo (honorific language), counter words, and the history of hiragana and katakana. Students grill Umino with testing questions, and the discussions regularly veer into linguistic and cultural differences between Japan and their own countries. While it was written originally for Japanese readers, the manga format makes the series quite approachable for foreign learners.

Explaining counter words

- An apple is ikko (一個) and a carrot is ippon (一本).

- We call these words for counting things josūshi (助数詞).

- English and German don’t have them. Chinese, Korean, and Thai do.

- Remember that something long and thin is ippon.

- So a snake must also be ippon.

- A snake is ippiki (一匹) because it’s an animal.

- But in China, tiao (条) is used to count both rivers and snakes…

- Japanese people count things differently depending whether they’re animate or inanimate.

(From Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo)

Standard is Safest

Umino began by teaching Japanese to Japanese students at an Osaka high school. As she explained in an interview with Nippon.com, she made the switch to instructing foreign students because she thought it would be fun to teach people who had chosen to learn. Although it became apparent that not all students were volunteers, many of them being forced to learn by their companies or parents, she soon came to enjoy the lively multicultural atmosphere of basic-level classes.

One recurring theme in the manga is the mismatch between the highly controlled language in student’s textbooks and what they hear in their everyday lives, which is often nonstandard or colloquial. Umino mentioned how some beginner students had asked her to teach the Kansai dialect as spoken in Osaka. “I’d tell them, ‘I like Kansai-ben, but there are some Japanese people who hate it!’” She suggests that it is safer to speak standard Japanese, because its neutral register makes it acceptable to anyone.

On the other hand, learners need to be able to understand both textbook and real-life Japanese. Umino is also reluctant to lay down any ironclad rule on speaking. “Sometimes, if you gauge the situation and decide that it’s OK to use a little Kansai-ben, then that can bring you closer to the person you’re speaking to.” The ability to smoothly switch between standard and nonstandard language varies from person to person, so students should decide for themselves what approach suits them best.

Cheating on homework (right)

- Hmm . . . how odd.

- Kim usually does so well.

- There were a lot of mistakes in your homework. What happened?

- But I got my Japanese friend to do it!

- Bring this friend to my class. Now.

(From Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo)

Practice, Practice, Practice

The Japanese the Japanese Don’t Know students pick up a lot of words from popular culture, including films, anime, and manga. Umino says that it is fine to do so, but that there is a time and place for putting that language into action. “I think it’s the same in every country. There are perfect moments for quoting lines from Star Wars and there are times when it will just be baffling.”

Umino also recommends that beginning students use words immediately after learning them by practicing saying them aloud. “Your mouth has to get used to them. You have to get used to the pronunciation of a foreign language, which has sounds that aren’t in your own language.” It is also important to write new vocabulary out by hand. “You can’t remember just by looking at the words, so write them out.”

This does not necessarily mean spending a great deal of time studying, though. “I think reading aloud and writing for five or ten minutes a day is OK. If you don’t do this, you’ll forget.” When it comes to that writing, though, Umino is no stickler for following the correct kanji stroke order. “My students often tell me that my stroke order is wrong. I don’t think it really matters, although some would say that accurate stroke order makes the completed kanji more beautiful.”

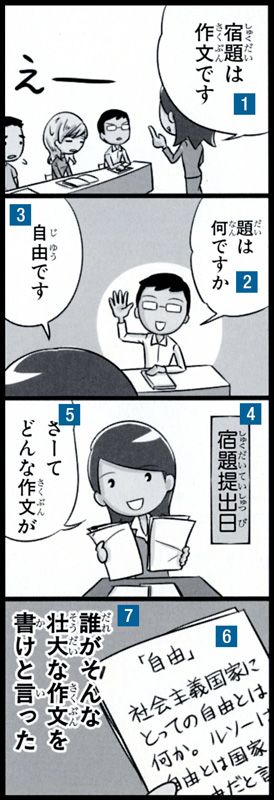

Today's homework (right)

- For homework, write an essay.

- What’s the topic?

- You’re free [自由, jiyū] to choose.

- Homework is due.

- Well, what kind of essays do I have here?

- “On Freedom” [自由] What does freedom mean in a socialist country? Rousseau says . . .

- Who said to write this kind of highbrow essay?

(From Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo 2)

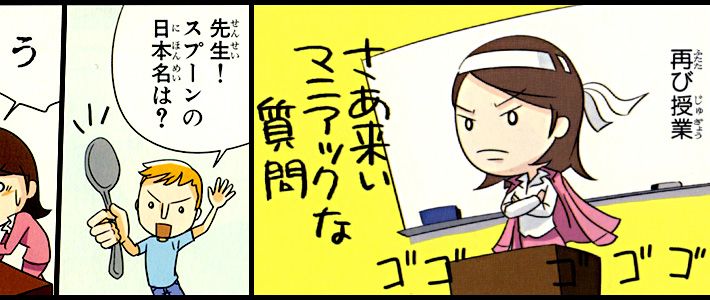

A New Kind of Written Language

Working as a Japanese teacher has made Umino more sensitive to changes in the language. She is fascinated by how new vocabulary emerges online. “There are lots of words used on Twitter that you never hear in daily conversation.” For example, instead of the standard furo ni hairu, meaning “to take a bath,” it’s common to see the word furoru. The term was coined by adding the verb ending ru to the noun furo, or “bath.” People tweet furotte kimasu to mean “I’ll be back after my bath.”

Words used almost exclusively in written language tend to have a stiff, academic image that creates a distance between speaker and listener and inhibits their use in conversation. As Umino points out, however: “It’s very strange that you don’t hear furoru in daily life. It’s written language only, but it’s not at all formal.”

A Love for Old Words

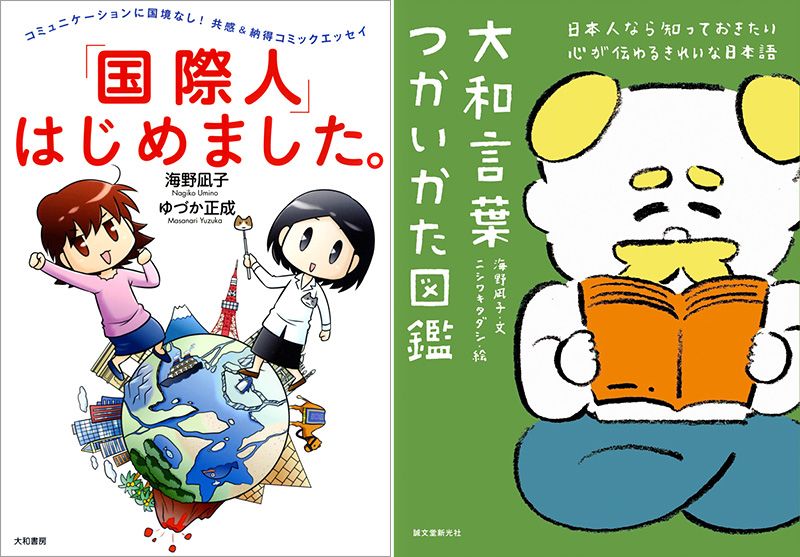

After completing her Japanese the Japanese Don’t Know series, Umino created the manga Kokusaijin hajimemashita (My Debut as a Global Citizen), this time with the artist Yuzuka Masanari. The book aims to encourage Japanese readers to overcome their worries about the language barrier and communicate more easily with people from other countries. It also introduces a range of cultural tidbits on customs, language, and other topics. As with the earlier series, the manga is supplemented with short essays written by Umino.

Umino’s recent books Kokusaijin hajimemashita (My Debut as a Global Citizen; image courtesy of Daiwa Shobō) and Yamato kotoba tsukaikata zukan (An Illustrated Guide to Using Yamato Kotoba; image courtesy of Seibundō Shinkōsha).

Umino’s recent books Kokusaijin hajimemashita (My Debut as a Global Citizen; image courtesy of Daiwa Shobō) and Yamato kotoba tsukaikata zukan (An Illustrated Guide to Using Yamato Kotoba; image courtesy of Seibundō Shinkōsha).

Her 2016 book Yamato kotoba tsukaikata zukan (An Illustrated Guide to Using Yamato Kotoba) demonstrates that she has a love for old words to match her interest in the latest neologisms. It unearths examples of native Japanese terms—known as Yamato kotoba—that date back to before the language was transformed by the large-scale introduction of Chinese loanwords. In the lexicon, Umino seeks to highlight beautiful words, many of which have fallen out of regular use, and suggest how they can be applied to everyday life.

One of these such words is kigusuri (気薬), which Umino describes as being a kind of medicine—in Japanese, kusuri (薬)—for a person’s feelings, or kimochi (気持ち). “When a friend is feeling a little down or lonely, kigusuri is something that helps to make her feel better. You might take your friend a few fun manga books as kigusuri.”

Umino’s interests and activities cover the full sweep of Japanese. Does she see it as a particularly challenging language for learners? “No, it’s not difficult. Japanese people all say that it is, but really it’s not that hard. It’s true that some aspects are difficult, but many more are quite straightforward.” Heartening words for students of the Japanese language everywhere.

(Originally written in English by Richard Medhurst of the Nippon.com editorial department. Based on an interview in Japanese with Umino Nagiko on May 24, 2016. Banner photo taken from Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo. All material from Nihonjin no shiranai Nihongo is included courtesy of Kadokawa. )