Contemporary Culture Going Global

Decoding the Charm of Japanese Video Games (Part One)

Economy Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Game-Culture Connection

During the past several decades, Japanese video games have captured the interest of people around the world. One reason for this may lie in aspects of Japanese culture. In short, one major factor underlying Japan’s emergence as a leader in the video-game sector has been an ability to evoke fertile images using limited resources—a talent also put to use in classical pastimes like haiku and traditional Japanese gardens.

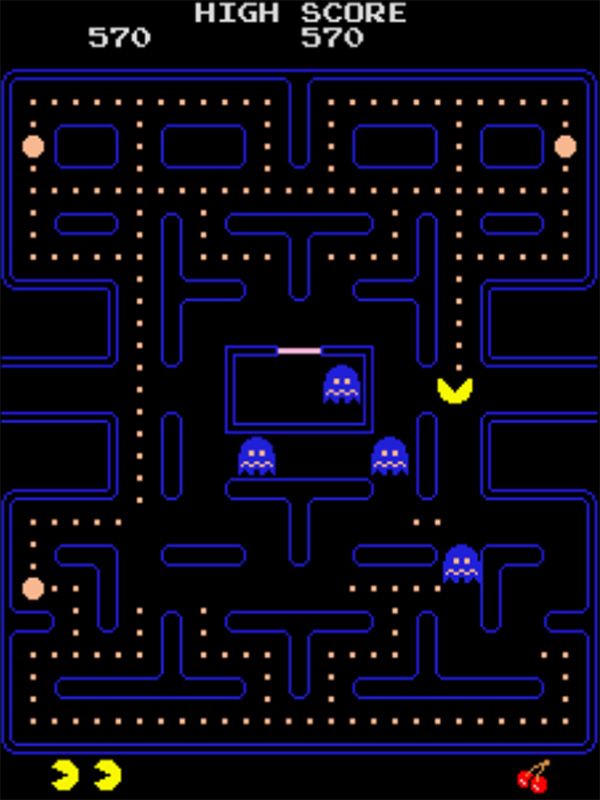

Pac-Man (1980, Namco [now Namco Bandai])

In this smash-hit arcade game, players must eat up all of the 240 dots placed in a maze while evading monsters.

Japan’s ukiyo-e prints, with their simple yet bold use of compositions and colors, provide another example of this cultural resourcefulness. The powerful artistic expression of these prints, mass-produced with inexpensive wood block techniques, astounded people around the world—notably the impressionist painters of nineteenth-century France. A century later, video games provided similar stories of simple compositions with global impact. The theme song for the video game Dragon Quest, for instance, was composed by Sugiyama Kōichi in 1986 using only the triadic chords that the sound system in Nintendo’s Family Computer (known as the “Famicon” in Japan and exported as the Nintendo Entertainment System) could produce, but ended up being a much-loved composition in subsequent years.

Anime, too, showcases this aptitude for using limitations as a springboard to creativity. Instead of the “full animation” of the Disney style, with its smooth movement throughout the frame, Japanese anime attained a global presence by employing the polar opposite “limited animation” approach. Anime maximized its impression with minimal resources through finely-honed methods that innovatively used a limited set of images to portray its stories.

Space Invaders (1978, Taito)

A shooting game in which players aim to destroy the invading aliens. It helped spark the enormous popularity of arcade games.

The Power of Suggestion

The graphics in early video games were far from realistic, but designers used what was available to create entrancing on-screen worlds. Their success in fully exploiting the meager tools of expression at the time drew on the imaginative power of mitate—a Japanese concept describing the use of one thing to evoke something else. The best example of this concept can be seen in the miniature bonsai trees, which suggest the majesty of nature on a much grander scale.

The classic video game Pac-Man, released in 1980, is an amusing case of using a simple image that brings to mind something else. Designer Iwatani Tōru’s inspiration for the famous dot-eating character was apparently the shape of a “partly eaten pizza.” The game was a massive hit around the world; its use of simple, evocative shapes opened the way for numerous games to follow.

A similar mitate approach to game development was evident in the 1978 Space Invaders, an extraordinarily popular game at the end of the decade. The idea for the video game drew on the previous hit game Breakout (1976), where players try to break through a brick wall using a rebounding ball. The creator of Space Invaders, Nishikado Tomohiro, used the same brick shapes as that earlier game to fashion the extraterrestrial invaders in Space Invaders; his graphical approach is also on display in the classic arcade games Western Gun (1975) and Balloon Bomber (1980).

The ideas and talents of the individual game designers played a huge role in the case of these early video games. One such creator was Endō Masanobu, who designed Xevious (1983). He managed to create a realistic science-fiction combat aircraft using a limited color palette and depicted a magnificent world that encompassed a grandiose mythology and a number of hidden characters.

Turning Limitations into Possibilities

Software for home video game consoles reached a new height in 1983, when Nintendo released its Family Computer. Initially, Nintendo relied on “transplanted” software from arcade games. But these games tended to be inferior to the arcade originals due to the inexpensive game consoles’ lack of power to reproduce the larger machines’ graphics and effects. To deal with this dilemma, developers began producing original software designed specifically for the home consoles.

One fruit of this effort was Nintendo’s 1985 Super Mario Bros., created by the company’s star designer Miyamoto Shigeru. This game drew on the side-view action of his earlier hit game Donkey Kong (1983), as well as the jumping gameplay and the goal of reaching different stages.

The challenge for game designers is how to create something with endless possibilities with a limited amount of resources. The result has been games that manage to incorporate all sorts of elements and features, offering players a richly nuanced experience, in a space far smaller than real life. These games are referred to in Japanese with the term hakoniwa (miniature garden) because they express a whole world using a limited amount of space, just as rocks and ponds are used in a traditional Japanese garden to evoke the broad sweep of the natural world. This was the aim that Miyamoto pursued in the creation of his 1986 game The Legend of Zelda.

Super Mario Bros. (1985, Nintendo)

This game sparked an enormous boom in the popularity of home video game consoles. It is registered in the Guinness World Records as the world’s top-selling game software.

The Legend of Zelda (1986, Nintendo)

This game placed a strong focus on unraveling mysteries, in contrast to action-packed outings like Super Mario Bros. It earned a strong fan base, particularly in North America.

The RPG Classic Dragon Quest

Dragon Quest (first version 1986, Enix [now Square Enix])

The first full-fledged RPG for a home console. Players assume the role of the game’s hero, who solves riddles in seeking to topple an evil lord and rescue an imprisoned princess.

Another designer who opened up new software possibilities for video game consoles is Horii Yūji, whose Dragon Quest series of role-playing games debuted in 1986. One factor behind the success of this franchise is its user friendliness. The game was designed so that any player could do well, thanks to the simple set of commands and easy-to-understand scenarios. The game series is a certified megahit, with 57 million units sold cumulatively, earning it the title of Japan’s classic role-playing video game.

The “miniature-garden” concept is also ingrained in Dragon Quest. In one early edition the game begins in a castle room, where the feudal lord and his vassals explain the goal of the player’s quest. In the confines of that room the player learns the key commands, such as how to talk to other characters or search treasure chests. This initial room serves as a sort of “instruction manual” for the novice player, who is not allowed to leave until those commands have been mastered.

Once the player sets foot outside of the castle, the castle of the strongest rival feudal lord comes into view. This destination appears to be nearby, but it is in fact a faraway place that cannot be reached until the player has accomplished certain tasks. The game’s map, which displays this ultimate goal while evoking the long journey of adventure, is the epitome of the “miniature-garden” approach to game design.

Part two of this article looks at how Nintendo eventually lost its position as market leader.

(Originally written in Japanese.)

video games Nintendo Sony Nintendo Entertainment System PlayStation