Contemporary Culture Going Global

Boys’ Love and the Bard: Brighton-Based Manga Artist Kutsuwada Chie

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

For Kutsuwada Chie, manga has always had a flavor of the forbidden. “My father didn’t allow me to read manga at home,” she recalls, “so I had to go around to a friend’s house.”

Not only did Kutsuwada ignore her father’s prohibition and read manga, she eventually ended up a manga artist herself (a decision that her father happily came to support, too). She now lives in Brighton, on the south coast of England, and has run manga workshops in schools, universities, and institutions including the British Library and Victoria and Albert Museum.

After coming to Britain to study English, Kutsuwada enrolled in a postgraduate linguistics course in syntactics. That, however, was not a success—“I kind of had a breakdown,” she notes—so she applied for and entered a course at the famous St. Martins College of Art in London. After also studying at the Royal College of Art, she embarked on a career in commercial illustration and manga.

“I graduated from one of the best colleges in Britain, but somehow I ended up making manga,” she laughs.

Kutsuwada’s workshops cover a range of manga, and she has worked in genres as varied as samurai fighting and horror. But her true passion are the manga genres known as yaoi and the related category of BL, or “boys’ love.” These fictional manga depict romantic relationships between male characters. Typically, these works are both drawn and read by women.

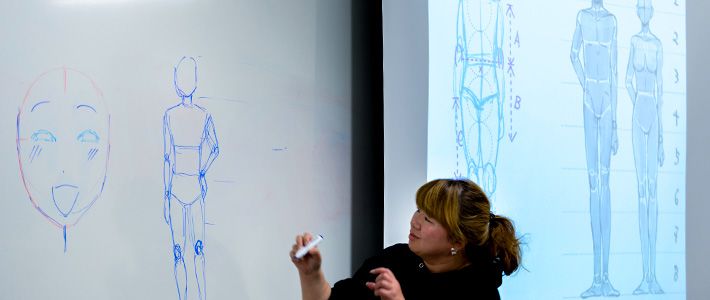

Kutsuwada presents at a workshop (left); participants take part in a group drawing activity.

Kutsuwada presents at a workshop (left); participants take part in a group drawing activity.

Kutsuwada believes that the popularity of the genre with women has much to do with deep-seated sexism in Japanese culture. Yaoi is, in essence, a reaction against conventional heterosexual romance manga, in which the female character often plays an old-fashioned and stereotypical role.

“We are a very modern culture, but women are still very much expected to be old-style good girls,” says Kutsuwada. “In that sexist society, you have to have a boyfriend, get married, have babies.”

Conventional manga offerings for women reflect that. But, says Kutsuwada, at a certain age, knowledge of the actual reality facing women in Japanese society can begin to interfere, and the manga fantasy is no longer pleasurable. Female readers find it hard to identify with the heroines of the stories.

“At some point we start doubting it,” she says, “but we still want to have romance.” A solution is the fanciful homosexual love stories of yaoi.

“With yaoi, you don’t have to put yourself into the manga because it is about boys and boys. In fact, it doesn’t have to be two boys. It could be two aliens or two nongender characters!”

But what about in Kutsuwada’s present home, which some might argue features more sexual equality than Japan? Does yaoi strike a similar chord for women in Britain?

Judging by the number of local female fans Kutsuwada has, it does. But British yaoi fans are in a slightly different demographic, often younger than the average 40-something yaoi fans in Japan.

“When I look at the British women who enjoy my work, they are often not very girly,” says Kutsuwada. Fitting in can be just as difficult for young UK women as for their counterparts in Japan, she notes.

“You have to be really girly to survive. We get very stressed and we need to let off that stress.”

One of Kutsuwada’s fans, Lisa Robinson, first encountered her work in the second volume of The Mammoth Book of Best New Manga. She describes the series excerpted there, King of a Miniature Garden, as “a beautiful bittersweet story about the love triangle between a sickly boy, his carer, and a girl with a mythical terminal affliction.”

“It was very poignant and beautifully drawn, and it made a big impression on me.”

“I love the BL genre because I was never really interested in heterosexual romance stories,” says Lisa, who identifies as a pansexual.

“I find ‘traditional’ romance very boring,” she adds. “Boys’ Love allows girls to be voyeurs witnessing the love of two beautiful men they wish happiness for. Even in really explicit scenes, it just really warms my heart to see a couple I’m really rooting for so in love.”

Yet, despite the presence of a solid base of enthusiastic fans, manga culture in Britain is still relatively new. While in countries such as France, Italy and the United States, comics are considered a major art form, in Britain they have often been dismissed as works for children. It is only relatively recently that Japanese anime and manga have made inroads into popular culture.

While perhaps not yet a household name, the Oscar-winning animator Miyazaki Hayao is well-known among cineastes. And in March 2017, a live-action version of Shirow Masamune’s Ghost in the Shell hit British screens. But manga remains something of a subculture.

Robinson suggests that UK fans of Japanese manga, and comics in general, tend to be “a little indoorsy, a little introverted, and a little marginalized.”

“LGBT, people of color, neurodivergents, and generally shy people make up basically all of my manga-loving friends,” she says. “All of them have a strong sense of empathy, care, and justice because of this, too. I think manga is a great tool to spread people’s horizons and view of the world.”

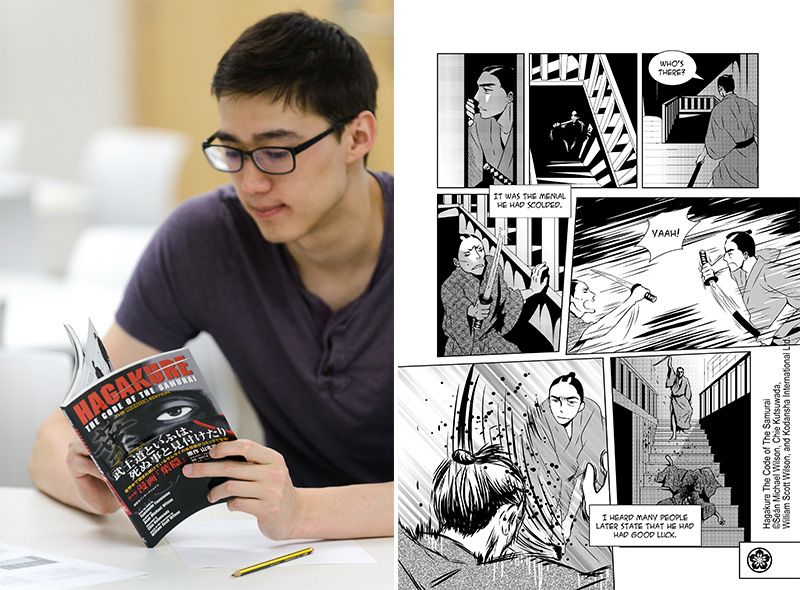

Shakespeare’s Fair Youth

In Britain, as in the United States, it is common for comics to be produced by artist-writer teams, and Kutsuwada has collaborated with writers on a number of works. One was a manga version of the Hagakure, the eighteenth-century guide to bushidō, the way of the samurai. She has also worked on a manga version of William Shakespeare’s As You Like It.

A workshop participant reading Kutsuwada’s Hagakure: The Code of the Samurai, based on Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s classic work (adapted by Sean Michael Wilson; published by Kodansha USA).

A workshop participant reading Kutsuwada’s Hagakure: The Code of the Samurai, based on Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s classic work (adapted by Sean Michael Wilson; published by Kodansha USA).

But her ambition is to produce bilingual manga that she writes and draws herself. Her most recent project is a manga version of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Famously, the majority of the 154 Elizabethan love poems are addressed to a young man, the “Fair Youth.” The nature of the relationship, platonic or romantic, between the bard and his muse has been speculated on for centuries.

But even with material so ripe for a yaoi adaptation, surely Shakespeare’s world is formidably distant from twentieth-century Britain, never mind Japan? In fact, Kutsuwada suggests that it is closer than we think.

“I think the great thing about those great classics like Shakespeare’s work is their universality. That’s why they are so adaptable,” says Kutsuwada. “Values might change, but emotions are so universal.”

As soon as she read the sonnets, Kutsuwada was fascinated with the idea of adapting them as manga.

“Sonnets, like many other poems, are in effect beautifully and carefully condensed emotions. Even a description of beautiful scenery is packed with emotions,” she says.

“Manga is a great medium to express how human emotions move. We use everything: background, a variety of speech bubbles, tempo, space, and much more to express the character’s feelings.”

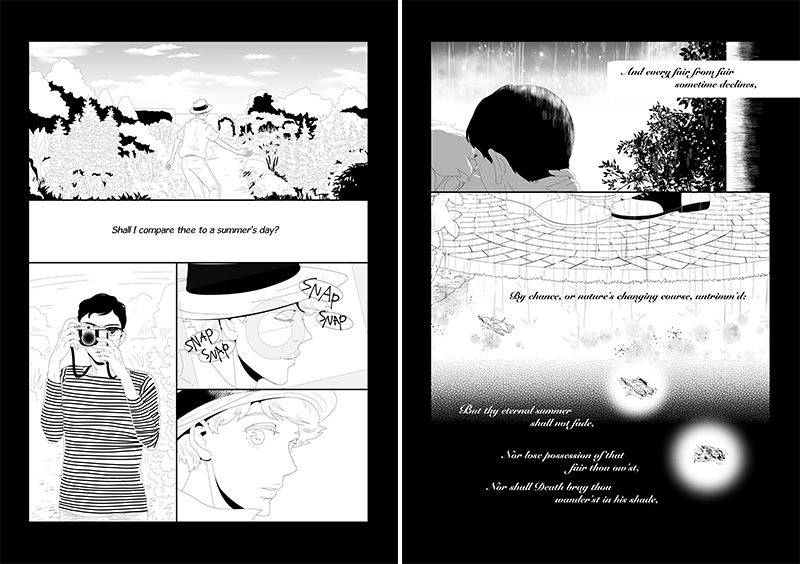

One of the pieces that Kutsuwada has adapted is the famous Sonnet 18, which begins:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?Thou art more lovely and more temperate . . .

Pages from Kutsuwada’s take on Sonnet 18.

Pages from Kutsuwada’s take on Sonnet 18.

“By using manga, I can show the facial expressions of the poet as well as the young man’s beauty,” says Kutsuwada. “I can realize the chemistry between them and present it to readers.”

She also points out a similarity between manga and theater, two very visual and story-based media.

“I think theater is similar to manga. If there’s a kind of story to tell and visuals involved, there’s a connection not only to manga, but to any comic and graphic novels.”

So maybe, in a different time and place, could Shakespeare have turned his hand to manga itself?

“Well, why not?” jokes Kutsuwada. “If he could draw well enough, there would always be a possibility!”

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: Kutsuwada runs workshop participants through a lesson in anatomical sketches. All photos © Tony McNicol.)