Celebrating the World’s Comic Creations

Emmanuel Lepage: Bringing Something New to BDs

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

“Maybe this is how the Japanese work, but you won’t let me relax for even a minute! Phew,” sighed Emmanuel Lepage, as he sat down for an interview between a panel discussion and a book signing on the day of the International Manga Fest (held on November 18, 2012, at Tokyo Big Sight), where he was an invited guest. Still, his eyes never lost their gentle smile as he raised a glass of red wine, brought by a staff member, and joked, “It’s Suntory Time!”—a line from the American film Lost in Translation, set in Tokyo. Our interview began in this kind of relaxed mood, like a chat during a break from work.

The Joy of Meeting His Idol

INTERVIEWER Thanks very much for making time in your schedule to talk with us.

EMMANUEL LEPAGE What an intense day! Unfortunately, I haven’t had time to look around the festival. But I had lunch with Ōtomo Katsuhiro! I’ve been a fan of his forever, so that was huge thrill. Akira was the first Japanese manga to be properly translated and published in France. France is flooded with manga now, but that was the very first one. Sitting in front of its creator, I felt like my younger self again. Gradually, our conversation turned to shop talk: things like narrative development, drawing techniques, and so on. It’s really exciting to be able to talk about work on equal terms with someone you worship.”

EMMANUEL LEPAGE What an intense day! Unfortunately, I haven’t had time to look around the festival. But I had lunch with Ōtomo Katsuhiro! I’ve been a fan of his forever, so that was huge thrill. Akira was the first Japanese manga to be properly translated and published in France. France is flooded with manga now, but that was the very first one. Sitting in front of its creator, I felt like my younger self again. Gradually, our conversation turned to shop talk: things like narrative development, drawing techniques, and so on. It’s really exciting to be able to talk about work on equal terms with someone you worship.”

Fear and Anger in Fukushima

INTERVIEWER I heard you went to Fukushima during your stay despite your busy schedule.

LEPAGE It wasn’t in the original plan, but things changed at the last minute. I was able to tag along with some journalists on a tour of the village of Iitate and other evacuation zones in a patrol car. I didn’t have time to prepare emotionally because I was busy with lectures and other things until the day before. So it didn’t really hit me where I was until I got to Fukushima and climbed in the car.

That’s when I saw the dosimeter. The same fear I felt in Chernobyl four-and-a-half years ago came rushing back. It was like déjà vu. But one thing was different. Right after the fear, an intense anger welled up inside me. I thought, hasn’t mankind learned anything from Chernobyl?

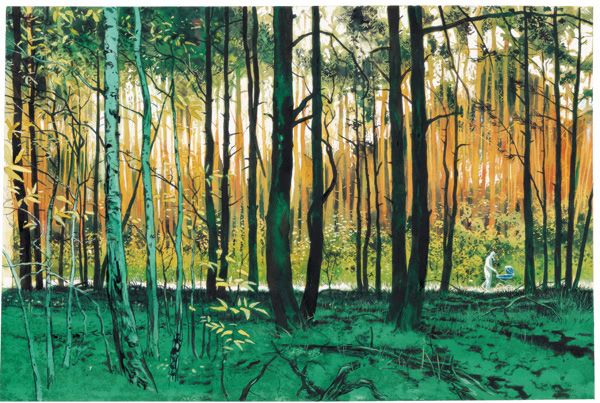

“Un printemps à Tchernobyl” ©Futuropolis

“Un printemps à Tchernobyl” ©Futuropolis

INTERVIEWER In 2008, you spent three weeks in a village near Chernobyl, and you wrote about your experiences there in Un printemps à Tchernobyl, which was published in France in 2012.

LEPAGE I was invited by a citizens’ group. The plan was to publish a record of my stay in the form of a sketchbook and use the profits to invite children exposed to radiation to France. I produced the sketchbook, but I wasn’t satisfied with it because it didn’t reflect what I felt. I wanted to change it into a bande dessinée, or a BD. So I chose to make myself a character and use the first-person voice. Documentary-style BDs have been appearing in France over the past few years. Mine is fairly subjective, so it’s very different than journalism. I like to travel, so I also enjoy sketching on the road. Despite the peculiar setting of Chernobyl, the book was probably an attempt to bring together important parts of myself that had been separate until then: travel, sketching, BDs, and life itself . . .

Taking a cue from a portrait of a poet

INTERVIEWER In the earlier panel discussion, you said, “Ultimately I think you’re really telling your own story though the characters that appear in your work.”

LEPAGE Even though you’re drawing fictional characters, you’re actually talking about yourself. I always try to get inside the characters that appear in my work. The best way to make your characters come alive and seem realistic is to draw them from your own feelings and experiences. I feel that’s how you draw actual human beings, rather than stereotypical human figures.

For example, there were hundreds of people sitting in the audience at the panel discussion, but each of them was sitting in a different way. The way someone sits says a lot about that person. That’s what I’m trying to do in my drawing. In other words, I try to express something unique about a person simply by the way he or she sits. If you don’t go after these various small details, I don’t think you can create a living character.

INTERVIEWER When I spoke with a young woman who came to the book signing, she said she was shocked because your work has such a different style from other manga she had read.

LEPAGE I want to bring something new to BDs. There are all kinds of possibilities: using different methods of storytelling, such as those from literature or film, or borrowing techniques from Japanese manga or American comics. The point is, you must always have a curious mind and stay attuned to other genres. For example, I got the inspiration for Gabriel, the main character in Muchacho, from Fantin-Latour’s portrait of the poet Rimbaud.(*1) Taking a cue from Rimbaud’s gaze and pose in the painting, I envisioned the character of Gabriel and fleshed him out. That’s how I look for new modes of expression.

Manga and BD: Cross-pollination

INTERVIEWER I’m sure you received many questions about the differences between Japanese manga and BDs during your stay. Do you ever get tired of them?

At the book signing at the International Manga Fest. Lepage carefully draws an illustration for each person. Next to him is Ōnishi Aiko, who translated “Muchacho” into Japanese.

At the book signing at the International Manga Fest. Lepage carefully draws an illustration for each person. Next to him is Ōnishi Aiko, who translated “Muchacho” into Japanese.

LEPAGE Not at all. Even if I get asked the same question ten times, it’s still the first time for the person asking it. When I was little, BDs were a fixed length: forty-six pages per volume. Obviously, the stories moved quickly, and they cut out a lot of details, so readers would stare at the pictures and let their imaginations run wild as they turned the pages. With manga, however, you surrender yourself to the action. It feels like you’re being swept away for thousands of pages. That’s exactly what attracted me to Ōtomo’s works—they were frighteningly dynamic. Since manga arrived on the scene in France, they have influenced BDs as well. There’s now a greater diversity of styles, and there are more and more options for developing longer storylines.

INTERVIEWER This was a great opportunity for you to meet many of your fans and to introduce your works and French BDs to more Japanese readers.

LEPAGE It’s my first time in Japan, but I’ve been invited to give lectures and workshops at various places, in addition to this event. Many people came to each of these gatherings, so I could really feel my works spreading little by little. I imagine there were also many people who came to this venue and saw my books for the first time. Just as manga is influencing young BD artists in France, I hope that BDs stimulate young manga artists in Japan. It’s pointless to create the same thing. What’s important is to produce new methods of expression.

(Interview photos by Hanai Tomoko.)

(*1) ^ Un coin de table (By the Table, 1872), by the French painter Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), depicts eight poets and writers sitting around a table, including the 18-year-old Arthur Rimbaud.—Ed.

art manga France Fukushima Chernobyl comics bande dessinee Otomo Katsuhiro Akira BD Emmanuel Lepage