“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Shunga: Japanese Erotic Art Takes London by Storm

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Eroticism as Art

Its beak caught firmly

In the clam shell,

The snipe cannot fly away

On an autumn evening.

(Yadoya no Meshimori)

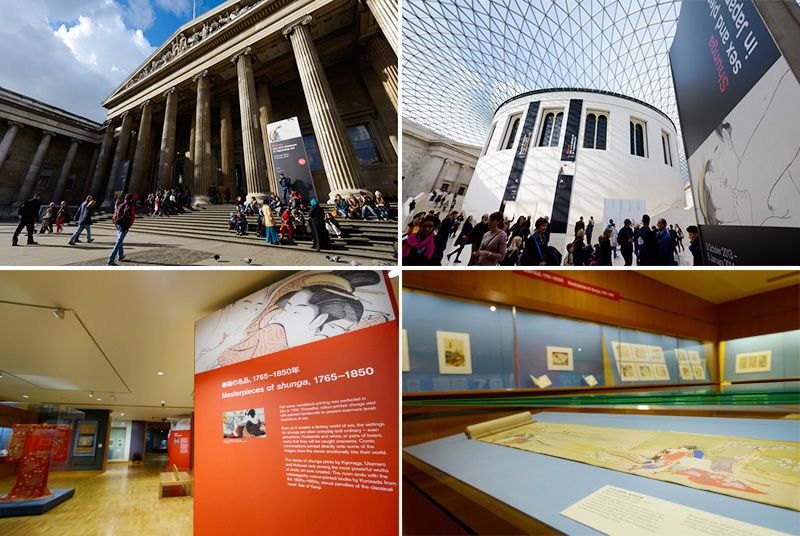

It doesn’t take long in the British Museum's exhibition of erotic woodblock prints, “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art,” to realize how inappropriate it would be to dismiss the artworks on display as mere “pornography.”

As the exhibition’s curator Tim Clark puts it: “I think people are surprised by the combination of the sexually explicit artworks and their beauty and humor—and ultimately the humanity coming through.”

Tim Clark, the exhibition’s curator

Tim Clark, the exhibition’s curator

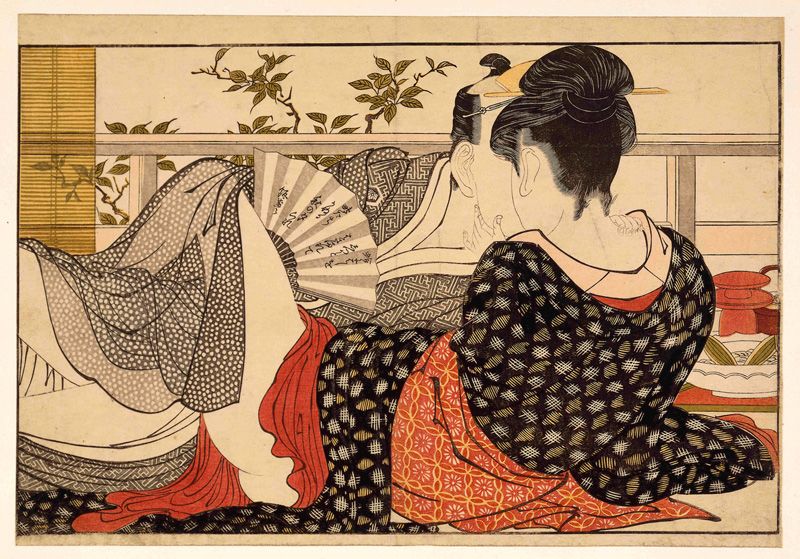

One of his personal favorites among the 165 works in the exhibition catalogue is a set of 12 woodblock prints by Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815). The figures in their sexual embraces are exquisitely drawn, and the radical cropping of the compositions draws the viewer deep into the scenes.

Clark says he particularly admires the “sensitivity and sophistication of the block carvers and printers” who turned Kiyonaga’s line drawings into woodblock prints.

The shunga exhibition is the result of a research project that began in 2009 and has involved 30 collaborators. Its aim is to “reconstitute the corpus and study it critically,” says Clark.

Around 40% of the exhibition’s content belongs to the British Museum, which has been collecting shunga since 1865. A significant portion of the rest comes from the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.

Clark’s preferred definition of shunga is “sexually explicit art”—with the emphasis on “art.” He observes that “the combination of something that is sexually explicit and artistically very beautiful is not one we’ve had in the West until recent times.” Remarkably, almost all the known Japanese artists of the period produced shunga.

As the exhibition text explains, early shunga in particular were made with fine materials. They were treasured and passed down through the generations. It’s recorded that one painted shunga scroll cost 50 monme of silver, enough to buy 300 liters of soy beans at the time.

Shunga had some surprising uses besides the obvious one. They were supposed to have the power to steel the mettle of warriors before battle and served as a talisman against fire.

Besides their entertainment value, shunga also served as sex education for young couples. And despite the fact that they were produced exclusively by men, it is thought that many women enjoyed looking at them too.

Printed by Nishikawa Sukenobu

Printed by Nishikawa Sukenobu

Shunga. Man seducing a young woman, with shamisen on the floor behind. Hand-colored woodblock print, with green background. The same print, uncolored, exists in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (1711–16)

Painting, handscroll, shunga. One of the 12 erotic encounters. A mature samurai and a youth embrace under a quilt. A woman adjusts the bedding. Ink, color, gold and silver pigment, and gold and silver leaf on paper. Unsigned. (Early seventeenth century)

Painting, handscroll, shunga. One of the 12 erotic encounters. A mature samurai and a youth embrace under a quilt. A woman adjusts the bedding. Ink, color, gold and silver pigment, and gold and silver leaf on paper. Unsigned. (Early seventeenth century)

Many of the prints show sexual pleasure that appears tender and reciprocal. “They connect very strongly to the everyday world,” says Clark. “Often the sex takes place in everyday settings and between husbands and wives.”

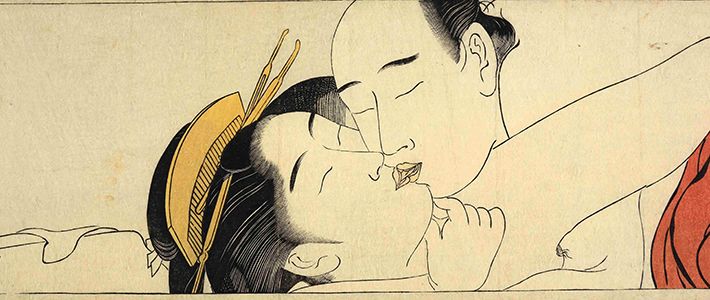

The print at the entrance to the exhibition is one example. Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow) by Kitagawa Utamaro (d. 1806) portrays lovers in the upstairs room of a teahouse. Their bodies are entwined beneath luxuriant clothing as he gazes passionately into her eyes. Her bottom peeks out from her kimono.

Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow)

Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow)

Printed by Kitagawa Utamaro

Shunga, color woodblock print. No. 10 of 12 illustrations from a printed folding album (sheets mounted separately). Lovers in private second floor room of a teahouse. Inscribed and signed. (1788)

A World of Humor and Satirical Intent

But many shunga could never pass for naturalistic portrayals of sex. This is obvious from the outsized genitals and the outrageous and humorous situations depicted in many prints. There is often an overlap between erotic shunga and what were known as warai-e, or “laughter pictures.”

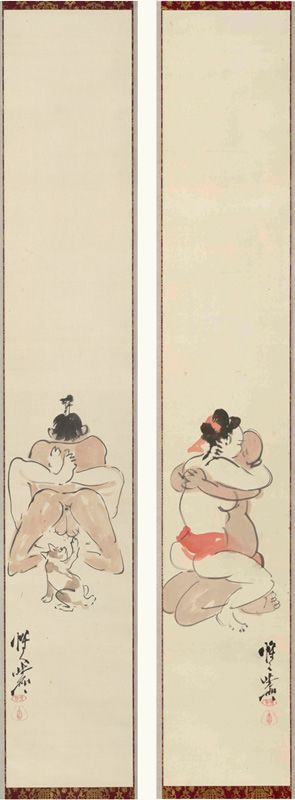

The left scroll of a painting triptych by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–89) from the early Meiji era shows a couple in a passionate embrace. Seen from behind, a playful and sharp-clawed kitten has had its attention drawn by the most sensitive part of the man’s anatomy. The viewer can imagine what happens next.

“I actually wanted to giggle at a lot of these pictures more than I did,” comments exhibition visitor Jess Auboiroux. “For some reason the Sunday afternoon crowd was in some kind of hushed reverie . . . surely this was not the spirit in which this art was meant to be looked at?”

The humor in shunga can be sharp-edged as well as bawdy. Like much popular culture during the Edo period, and indeed sexually explicit art in more modern times, there’s an element of rebellion.

“Shunga consistently takes more serious genres of art and literature and parodies them—often playfully, but sometimes for rather sharper political ends,” says Clark.

One example is the shunga versions of books of moral instruction for women. Sometimes the sexually explicit parodies are so similar they look as if they were made by the same artists and publishers as the originals. In fact, they certainly did come from the same publishing milieu.

But when shunga satire got too close to the bone, censorship quickly followed. Declared illegal in 1722, shunga production was affected for two decades. There were similar crackdowns in later years, but shunga never disappeared. In fact, it skillfully exploited its semilegal status to continue pushing the boundaries of satire. Many shunga are still striking in their imagination and daring.

One set in the exhibition features portraits of kabuki actors and close-ups of their erect penises. The pubic hair is styled to match the actors’ wigs, and the bulging veins to match the lines of their makeup.

Shunga in Modern Japan

Uwaki no sō (Fancy-free Type) from “Fujin sōgaku jittai (Ten Physiognomies of Women)”

Uwaki no sō (Fancy-free Type) from “Fujin sōgaku jittai (Ten Physiognomies of Women)”

Printed by Kitagawa Utamaro

Color woodblock print with powdered mica ground. Girl with head turned, breast showing, wiping hands on cloth. Inscribed, signed, sealed and marked. (1792–93)

Ironically, not long after shunga started to become known in the West (US Commodore Matthew Perry was presented with shunga as a “diplomatic gift,” and Picasso, Rodin, and Lautrec were all fans of the genre), the Japanese decided that it was time to draw a veil over the art form. Suppressed for many decades, it was not until the 1970s that a shunga exhibition could be held in Japan.

This exhibition reaffirms shunga’s importance to any account of Japanese art. Yet, even now, according to the researchers, an exhibition on the scale of the British Museum’s might be difficult to stage in Japan.

“It is clear that shunga was an integral part of Japanese culture, at least until the twentieth century,” says Andrew Gerstle, professor of Japanese studies at SOAS, University of London. “People are surprised that it has not yet been possible to show the exhibition in Japan itself.”

According to Clark, the reaction to their exhibition, both in Britain and Japan, has been “pretty phenomenal.” Halfway through the exhibition, they are already close to reaching their target for visitor numbers.

Exhibition collaborator Yano Akiko, a research associate of the Japan Research Center at SOAS, noted the team put a huge amount of effort into explaining the “complex premodern phenomenon” to visitors.

“I was a little worried that we might have tried to provide too much information,” she says. “But most visitors seem to fully engage with the content, understand what we wanted to convey, and enjoy the exhibition. It has been the best response we could have imagined.”

(Photographs and original English text by Tony McNicol. Images of shunga courtesy of the British Museum.)

▼Reference

The British Museum

Kawanabe Kyōsai Memorial Museum

Edo-Tokyo Museum

Japan art Shunga ukiyoe Bijinga Waraie British Museum Kitagawa Utamaro Kawanabe Kyosai Tim Clark