“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

Wood, Mold, and Japanese Architecture

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Recently, a European architecture student asked me, “Historically, why did the Japanese build almost exclusively with wood even though fires were so common?” Fire is certainly a problem for Japanese wood construction, a fact reflected in the strictness of current fire mitigation codes. However, it appears to have been the least of the frequent natural disasters that drove traditional Japanese building forms. Three other considerations were more pressing: mold, typhoons, and earthquakes, in that order.

The kitchen in this new home is separated from the living area by a 600 mm sagarikabe ceiling divider to slow the spread of smoke and fire. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

The kitchen in this new home is separated from the living area by a 600 mm sagarikabe ceiling divider to slow the spread of smoke and fire. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

A Constant Presence

Mold plagues twentieth century buildings all around the world. In the drive for energy efficiency, developed countries introduced new methods of insulation and pushed to limit air flow between the inside and outside of houses. Unfortunately, mold-related problems and “sick house” syndrome soon proved that moisture control and proper ventilation are absolutely necessary to the health of inhabitants. To achieve these, contemporary construction relies on structural and mechanical ventilation that adds significantly to the cost and complexity of buildings.

Much of Japan has ideal conditions for mold and many other types of fungi. Temperatures rarely drop below freezing or rise above 35°C, providing an ideal temperature band for growth; most importantly, the humidity can linger above 70% for weeks at a time, particularly during the warm summer months. The onset of the rainy season is when mold can become truly destructive. Women caution that long hair may mildew if not properly dried and countless pairs of shoes have moldered while shut up in a shoe closet.

Traditional wooden construction fought mold by raising the building above ground level and leaving walls mostly open so that air could flow freely under, around, and through the entire interior space. Buildings over 300 years old still in their original state are usually “lightly inhabited,” containing very little furniture and few other fittings. Temples, shrines, palaces, and homes of the traditionally wealthy fit in this category.

The ground floor of a traditional minka is almost entirely opened to the free flow of air. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

The ground floor of a traditional minka is almost entirely opened to the free flow of air. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

Private homes were typically built with heavy timbers and excellent natural ventilation. Since relative humidity can be high even in winter, they had abundant air flow even when shut to the outside elements—through spaces between wooden shutters and paper doors, between walls and roof, and frequently through an entirely open smoke outlet.

All of this ventilation served to make traditional Japanese homes fairly comfortable in summer, but seriously uncomfortable in winter. However, wearing many layers of clothes and getting chilblains on your fingers was apparently a small price to pay for avoiding mold.

This farmhouse is raised approximately 50 cm above ground level. Almost all of the ground-floor walls can be opened, allowing the free flow of air. The practice of leaving the under-floor area open is now generally illegal in cities, however, as the crawl space acts like a duct sucking in oxygen in the case of fire. (© Anne Kohtz)

This farmhouse is raised approximately 50 cm above ground level. Almost all of the ground-floor walls can be opened, allowing the free flow of air. The practice of leaving the under-floor area open is now generally illegal in cities, however, as the crawl space acts like a duct sucking in oxygen in the case of fire. (© Anne Kohtz)

The Culture of the 30-Year House

Ancient Chinese chroniclers noted that the religious observances of the peoples of the Japanese archipelago concerned mainly cleanliness and purity, elements that mark many cultural and religious practices to this day. The facility of mold growth in Japan could in part help explain why the culture of cleanliness was so prevalent and why “impurity” remains taboo.

Japan is widely perceived to be very traditional, but there is a strong preference among Japanese for the new. Major construction companies make no secret of the fact that they design their homes to last approximately 30 years, after which the house is expected to be torn down and replaced. The idea that a house is “old” after only 30 years is astonishing to Western construction professionals, but rebuilding is a perfect means of entirely eliminating mold and insect infestation—nontrivial concerns in the Japanese climate.

The dressing, size, and cutouts on the center beam indicate it was reused from a different house. Japanese post-and-beam wood construction is particularly suitable in a culture of frequent rebuilding, as it allows many of the most valuable parts of a building to be recycled. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

The dressing, size, and cutouts on the center beam indicate it was reused from a different house. Japanese post-and-beam wood construction is particularly suitable in a culture of frequent rebuilding, as it allows many of the most valuable parts of a building to be recycled. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

This culture of frequent rebuilding has ancient roots as well. Until the eighth century CE, the death of an emperor was cause to move the palace, and in some cases the entire imperial capital. Political motives aside, such an idea is only possible if built structures are viewed as relatively impermanent.

This idea is apparent in many aspects of culture during the Edo period (1603–1868). A popular saying was that fire was one of Edo’s two “flowers” since the city “bloomed” frequently. Celebrated in stories and wood-block prints during the period, these conflagrations significantly lowered the average lifetime of buildings.

Moving a house meant discarding everything but the timber structure, disassembling that framework, and reassembling the timbers with a fresh roof and infill walls. Any parts that may have become rotten were replaced at this time. This proved an ideal way to mitigate any damage from mold and insects while preserving the economic benefit of the most durable parts of a house. Indeed, we find extremely old recycled beams and columns in many farmhouses today, where the lumber was reused from a previous construction.

Wood vs. Metal

Guilds, protectionism, and political decisions of the Togukawa shogunate restricted the use of metal fasteners in construction during the Edo period. This was a major factor that drove the development of Japanese all-wood joinery even after steel became generally available. Metal fasteners, however, cannot rival the longevity of all-wood joints unless installed in well-cured wood and protected from contact with air. In imperfectly cured wood, they can be loosened by seasonal shrinkage and expansion of the surrounding material, and when exposed to the air they are subject to rapid oxidation in Japan’s humid climate. Additionally, regular stress over time will result in metal fatigue.

Conversely, an all-wood joint gains in strength as the wood ages and individual cells harden. Calculations show that wood joints can be more structurally sound centuries after their initial construction. In general, wood gains in strength for 200–300 years after being cut. Strength gradually declines after that point, but only after about a thousand years will a properly cured timber beam be reduced to the strength it was when it was originally logged.

Rusted nails and fasteners recovered from the deconstruction of a 60-year-old thatched tea house. (© Anne Kohtz)

Rusted nails and fasteners recovered from the deconstruction of a 60-year-old thatched tea house. (© Anne Kohtz)

A joint in a renovated Edo-period farmhouse. The owners believe the house to be at least 250 years old. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

A joint in a renovated Edo-period farmhouse. The owners believe the house to be at least 250 years old. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

Typhoons and Earthquakes

Next to mold on the list of natural disasters, the high winds and torrential rains of regular typhoons are another great argument for building with wood. Frequent heavy rain encourages the use of very deep overhanging eaves to protect walls, while the response to high winds was heavy roofs that wouldn’t blow off.

This renovated thatched home has deep eaves protecting the walls, and the roof is weighed down by a tile cap. The thatch is also tied to the roof structure with straw ropes. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

This renovated thatched home has deep eaves protecting the walls, and the roof is weighed down by a tile cap. The thatch is also tied to the roof structure with straw ropes. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

Heavy, cantilevered roofs are impossible to build without an elaborate timber structure, especially without access to metal braces and fasteners. To resist typhoons, these heavy roofs would ideally be supported with thick stone or masonry walls. But in a country where devastating earthquakes are almost as common as devastating typhoons, this is dangerous and impractical. (Not to mention the fact that uninsulated masonry or concrete walls will literally weep with condensation during the rainy season.)

In traditional Japanese wood construction the timber structure is almost all open to visual inspection. This means any water entry, such as from a leaky roof, can be easily identified and dealt with before mold has a chance to move in.

The structure of this remodeled gate building is visible both from inside and outside, so any problems can be easily identified and repaired or replaced. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

The structure of this remodeled gate building is visible both from inside and outside, so any problems can be easily identified and repaired or replaced. (© Architectonic Atelier Yuu)

Earthquake-resistance is the third major reason for building with timber. Modern Western houses are constructed as a solid box firmly attached to a foundation, so earthquake resistance is achieved through ensuring that the walls are robust enough to resist lateral shaking. As result, though, the building will move with the ground, causing the occupants to feel the whole force of the earthquake.

On the other hand, traditional all-timber joints are flexible, so that much of the lateral energy of an earthquake can be absorbed by the flexing of the joints themselves. This allows a building with a heavy roof but no solid walls to remain standing even during strong shaking. Many ancient timber buildings in Japan are constructed similarly to a wooden chair, with wall-free support pillars connected both at the top, where the roof rests, and by braces lower down. This allows for safe support of a dynamic, top-heavy weight.

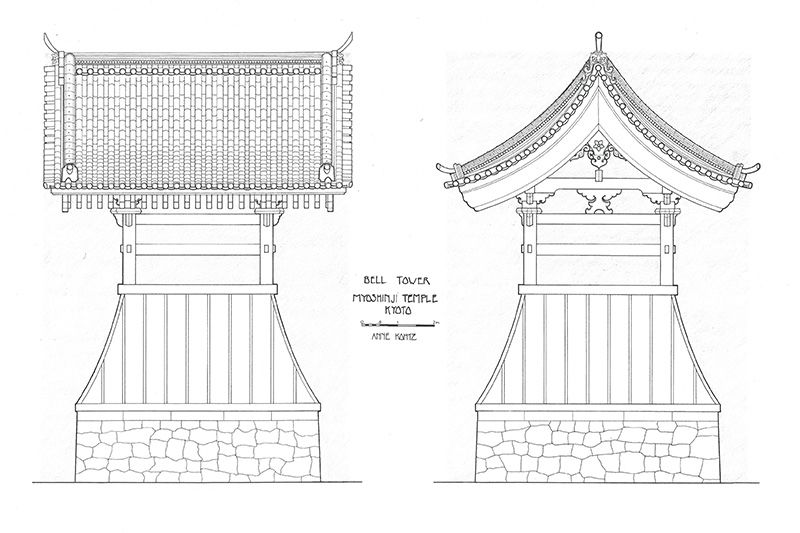

A drawing of the elevations of the bell tower at Myōshinji in Kyoto. The central structure has no solid walls at all, much like a wooden chair. (© Anne Kohtz)

A drawing of the elevations of the bell tower at Myōshinji in Kyoto. The central structure has no solid walls at all, much like a wooden chair. (© Anne Kohtz)

Most traditional buildings were not attached to any foundation and had no basements. During an earthquake, the structure might be expected to jump off the base stones, wattle-and-daub walls would break, and timbers might twist or bend. However, a properly constructed timber building could be expected to remain upright. In fact, even in contemporary construction, base isolation—that is, entirely separating a building from its foundation to let it slide freely during an earthquake—is becoming the gold standard for seismic design. Traditional base isolation (simply placing a structure on a solid base without attaching it), however, is generally illegal in Japan.

An Abundance of Wood

A final consideration in the preference for wood in traditional construction is the ready availability of lumber in Japan. Common types of wood including cryptomeria, cypress, and pine are generally ready for harvest and use after just 40–60 years of growth. Cryptomeria and cypress in particular are resistant to both mold and insects, making them suitable building materials for the Japanese climate. And, as noted above, the benefits of building with wood timbers tended to outweigh the danger of fire, a threat that generally allowed time to escape and could in many cases be put out before causing serious damage.

Happily, Japanese carpenters have made the most of wood construction techniques over many generations, bequeathing us with a trove of beautiful construction that can inform a modern, sustainable, safe, and mold-free lifestyle.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: A newly renovated minka farmhouse. © Architectonic Atelier Yuu.)