Whisky, a Spirit Imbued with Culture

Guideto Japan

Economy Society Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Whisky Market Shrinks to a Quarter over Three Decades

Japan’s economic growth after World War II played a significant role in shaping the culture of drinking Western spirits, notably whisky, in Japan. Until then, drinking culture was centered around sake. But as Japanese society and culture evolved as it assimilated influences from the West, people came to drink more beer and whisky.

Consumption of beer rose as refrigerators became common fixtures in homes, and by the 1950s it had surpassed sake to become the country’s most popular alcoholic beverage. Although overall alcohol consumption grew as Japan’s population increased, sake consumption diminished after peaking in 1975.

Meanwhile, the whisky market enjoyed steady expansion until 1983. But when a shift in U.S. consumer preferences toward white liquors, such as vodka and gin, reached domestic shores, it took the form of a boom in shōchū and chūhai (shōchū-based cocktails). From 1983, consumption of schōchū doubled, overtaking whisky in just a few years. Whisky consumption, which had enjoyed consistent growth in the postwar decades, in turn plummeted in a matter of years from its 1983 high, falling by as much as one-fourth.

In 1990, Japan abolished its unique system of grading whisky. Although this lowered the average price of the liquor, the market continued to shrink. By around 2000, production was down to a quarter of its peak nearly two decades earlier and only in recent years has whisky started to regain lost ground.

The Beginning of Whisky in Japan

Compared to Western countries, the history of whisky in Japan is relatively short. It was in 1924 that Kotobukiya—the predecessor to Suntory—unveiled the nation’s first domestic whisky, using the provocative slogan, “Awaken, people! The days of blindly admiring imports are past. Get drunk, people! Here is our supremely delicious domestic liquor, Suntory Whisky!”

It can be inferred from the slogan that imported whisky was already prized in Japan, but at the time the whisky market was minuscule, serving a select number of wealthy individuals who enjoyed the drink as a way to connect with Western culture. For most people, whisky was a beverage that they might have heard about, but could only dream of tasting. It was not until the 1960s that whisky came within reach of the average Japanese.

Japan’s Unique Whisky Classification System

From 1962 until liquor taxation was reformed in 1989, whiskies were classified primarily according to their mixture ratios into special, first, and second grades and then taxed accordingly. The differences between the tax rates for each grade were substantial, and Japanese whisky came to be characterized, more so than in other countries, by a hierarchy between brands. As a result, the market grew into two divisions: second-grade whiskies for the mass market and upscale special-grade whiskies.

In a developing economy, expensive products often take on a special value as objects of desire. Whisky epitomized this phenomenon in Japan, and special-class whisky was highly valued in the gift market. By the time the classification system was abolished, the tax on special-grade whisky was about ¥1,400, making up over 40% of the ¥3,170 retail price of a typical product. By comparison, second-grade whisky had a price tag of ¥720 that included a liquor tax of about ¥170. As living standards improved, the focus of the market shifted from second-grade whiskies (such as Suntory Torys, Suntory Red, and High Nikka) to their special-grade siblings.

Differential taxation under the classification system led to greater price disparities between whiskies of different brands, encouraging manufacturers to take up the strategy of selling multiple brands. In the following section, I give a brief overview of Japan’s whisky consumer scene at the time.

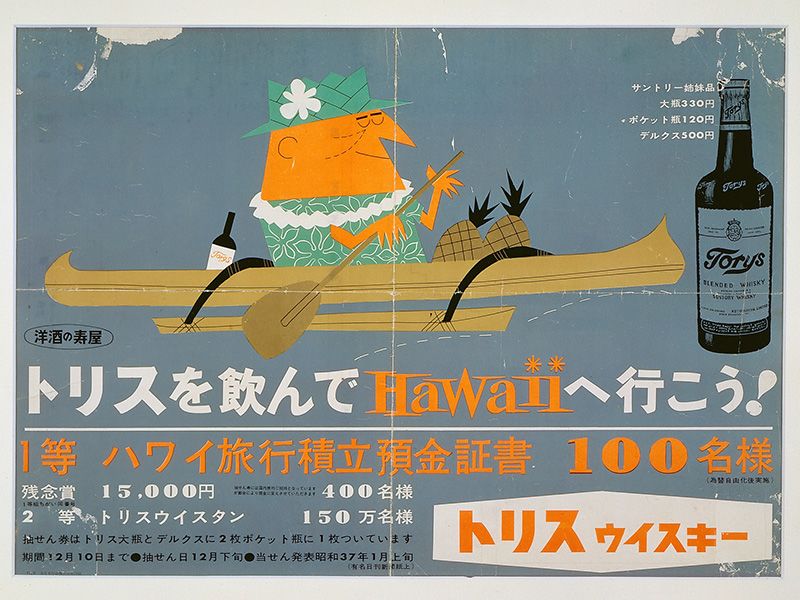

Drink Whisky and Win a Trip to Hawaii

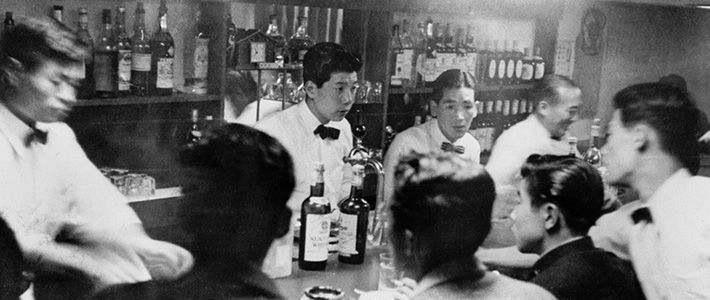

Whisky made its debut as a symbol of Japan’s postwar recovery, becoming a drink that not only intoxicated but was also imbued with culture. In the 1960s, popular Western-style bars with “Torys Bar” and “Nikka Bar” prominently displayed in their names popped up across the country. A 1961 advertising campaign even invited people to drink Torys whisky and win a trip to Hawaii. At a time when overseas travel was no more than a fantasy for the average Japanese, the public came to widely acknowledge the new spirit as a purveyor of dreams.

An ad for the “Drink Torys and go to Hawaii” campaign. (Photograph courtesy of Suntory.)

An ad for the “Drink Torys and go to Hawaii” campaign. (Photograph courtesy of Suntory.)

As Japan enjoyed remarkable economic growth in the 1970s, an advertising copy for Suntory Old whisky became all the rage. It read, “A decade ago it would have been a cup of hot sake. . . . To finish the day. Kuromaru(*1).” The ad, which depicted a sushi chef sipping top-grade whisky instead of sake after work, succeeded in transforming the image of the drink from that of a special, foreign liquor only consumed in Western-style bars to a part of everyday life. Annual sales of Suntory Old, the company’s flagship product at the time, were about 1 million cases when the ad was launched in 1970. This rose to 5 million in 1974, 10 million in 1978, and 12.4 million in 1980. In merely a decade, the brand had grown into one of the world’s bestselling whiskies.

It was also during this period that mizuwari, or whisky and water, became a standard way of enjoying the drink. Adding water serves to soften the bite of the hard liquor by reducing the alcohol volume from 40% or higher to 15%, a more familiar territory to the Japanese palate. People in southern Kyūshū had been drinking shōchū, the area's preferred tipple, in a similar manner for generations, diluting the alcohol level of the clear liquor with hot water to 15% in a drink known as oyuwari. The introduction of mizuwari paved the way for whisky to be imbibed not just as a digestif, but also as an accompaniment to dinner.

Moreover, whisky took on a modern image while sake became “old and outdated.” Once seen as a lofty beverage from the developed world, whisky was now a familiar everyday drink. This led to the rise of “snack” bars, a sort of Western-style incarnation of the traditional izakaya, as places to drink whisky.

Snack Bars Lift Whisky Market

Bars known in Japan simply as sunakku (“snack”) flourished from the 1970s to the 1990s. These cozy establishments, often with mostly counter seating, serve light fare as well as alcohol and feature hostesses to entertain guests. Snack bars played a major role in expanding whisky consumption. It is from here that mizuwari and the practice of “bottle keep,” where customers purchase a bottle of their preferred spirit and the bar stores it for future visits, spread. Whisky manufacturers found bottle keeping convenient for their business, and having core establishments that carried their product line made it easier to build brand awareness and provide sales support.

At a snack bar. Most establishments have karaoke machines. © Jiji Press

At a snack bar. Most establishments have karaoke machines. © Jiji Press

By offering several brands of varying price ranges, manufacturers encouraged a shift to higher-class products within the same whisky category. Drinking more expensive whisky than others served as a form of conspicuous consumption. Although patrons at snack bars would of course pay for their fare, their reason for being there was not really the food or drinks. Rather, they were there to receive the services of the mama (female owner) and hostesses. In the 1970s, these services mostly consisted of conversation, but singing and dancing took over with the advent of karaoke in the 1980s. Drinking expensive beverages at snack bars was a way of satisfying one’s desire for attention, meaning that few drinkers ever went on to explore whiskies of different flavors in the same price range.

Widening Selection of Whiskies

The 1980s onward saw the emergence of new kinds of establishments, such as cafe bars and “shot” bars, where customers could choose from a wide selection of whiskies served by the shot or mixed in cocktails. Bourbon whiskey became popular, especially among the younger generation, and other Western alcoholic beverages available to the public began to diversify as well. This was spurred on in part by the appearance of parallel imports, which undermined the established system in Japan of sole import agents designating prices.

Standard Scotch whiskies came to be sold at discount prices, dragging down their brand value and eroding their market share. Premium Scotch whiskies, meanwhile, initially spread their consumer base. But drops in prices, and hence their perceived value, eventually stamped out demand in the gift market, and sales in Japan dwindled.

The whisky market thus contracted as a result of lower prices, defying standard marketing logic. With the high-class market lost, the industry would go on to restructure itself around preference-based values, such as flavor and aroma, as exemplified by malt whisky.

Brands as Reflections of Social Status

In the decades leading to the 1980s when whisky was widely imbibed as the spirit of choice of many Japanese, whisky brands served as icons of the social status, ideology, and other aspects of the drinker. It was typical for individuals to graduate to higher-class brands as their disposable income rose: from Suntory Red to White to Old to Reserve, for instance. Moreover, different brands did not always mean differences in hierarchy. There were more unique whiskies for the individual minded, such as Suntory’s Kakubin brand, whiskies by Nikka, and Bourbon whisky, allowing drinkers to make statements depending on what they drank. All of this goes to show that whisky had great social significance for the Japanese of the time.

The hold that whisky came to have on Japanese society was built on Suntory’s many years of delivering marketing messages to people of every generation. The firm had engaged in philanthropy from early on, developing a reputation not just as a manufacturer of Western alcoholic beverages, but as a cultural company. In the early 1980s it became the top choice among college students as the most desirable company to work for.

But the whisky market had grown beyond itself, based more on cultural perceptions than on differences between brands in flavor and aroma. Japan’s whisky market as a whole would never again take an upward swing after the chūhai boom hit in the early 1980s.

Getting the Highball Rolling

After several years of promoting the highball (whisky and soda water), Suntory has succeeded in breathing new life into the whisky market. It has put a good deal of time and effort into instructing establishments on their highball recipe, including the alcohol content and temperature, to maximize the taste of the whisky. As a result, Suntory has been able to create new demand beyond the traditional target audience for whisky.

There has always been a certain number of people who do not like the sweet taste of chūhai. What this group wanted was dry, sparkling, refreshing, low-alcohol beverages that they would never weary of drinking, and the highball fits the bill. This demand has won the whisky market new customers, coming from consumers of diverse markets, including beer and chūhai drinkers.

This new consumer base may, however, be limited to their use of whisky in highballs. Getting them to like whisky in itself is another chapter down the road. Successfully initiating these newcomers into the more authentic ways of enjoying whisky will be key to further boosting the whisky market as a whole.

(Title photo: Inside a Torys bar, circa 1955. Photograph courtesy of Suntory.)

(*1) ^ Suntory Old was also known by the nickname Kuromaru, meaning “black ball,” in reference to its black, rounded bottle.